When Germany declared war on France on 3 August, Lieutenant Pierre Perrin de Brichambaut (MF8) was stationed close to the border, at Nancy. The following day he received orders to make a reconnaissance around Château-Salins. Better still, he was given permission to go armed: ‘Marvellous words. Thrilling. I really did jump … for joy. Into the fuselage, alongside my mechanic, went my good old .351-calibre hunting rifle, my automatic pistol and a box of (the rather ill-named) ‘Bon’ flechettes. We took off armed to the teeth, full of enthusiasm. Just think, our first real taste of action.’

Crossing the lines at 1,400 metres, ‘a pretty incredible height … for the time’, they soon ran into trouble. ‘Sapristi, they’re firing up at us, sir!’ called the mechanic/observer as holes began appearing in the fabric of the wings. Perrin showed no hesitation: he promptly let off a few shots from his carbine, dropped his flechettes on to the Germans below and emptied his pistol at them. With that, the pair flew off, ‘very pleased with [them]selves’.

Within hours sensational reports filled the newspapers: Roland Garros had rammed a German Zeppelin on the French side of the frontier, pilot and airship both lost! No, the pilot was Marcel Brindejonc des Moulinais! No, Brindejonc had blown up an enemy arsenal with a huge number of casualties! The reality was somewhat different: Brindejonc, a celebrated pre-war flyer and long-distance racer, was stuck in the barracks at Saint-Cyr. ‘I’ve just devoured some “monkey” [i.e. ration meat],’ he wrote to his friend, journalist Jacques Mortane. ‘I’m sitting on my bed. We’re sweeping up so I’m covered with dust from the crumbly cement floor and it’s making me sneeze. I can’t bear the thought of having to live like this for the next two years – no freedom at all and too tired each evening to venture one step beyond Saint-Cyr. There are sixteen of us sharing the room [and] my mechanic is available whenever I want him. It’s much better than ordinary infantry quarters but some things are still pretty dire. Life’s much harder in 3rd Company than 1st because the last lot ruined things for us by taking liberties. I’d like a few minutes to study or read. But no. All I can do is take snaps of barracks life [and] that’s no fun at all…. I’d like to make myself useful now I’ve learned how to handle a gun and perform an about-turn. I’m a bit brassed off. Still, that’s progress. Last month I was totally brassed off. Did you see that I’ve looped the loop four times as a passenger? It’s capital!’ Fortunately for Brindejonc, his posting came through quickly. By mid-August, ‘overjoyed to be at war’, he was serving with DO22, attached to Fourth Army in the Ardennes.

At the start of hostilities French planes outnumbered German. However, the limited experience gained on manoeuvres had done little to prepare the squadrons for the realities of war and they performed poorly in the first weeks of the conflict, hindered by inadequate planning, training and tactics. ‘It’s a pity … we couldn’t have delayed the outbreak of war by six to twelve months,’ commented one pilot on 7 August. ‘Our role could have been that much greater. We might have planned the air war instead of making it up as we go along.’ Roland Garros, soon to be posted to MS23, thought France had failed to make use of the experience of its civilian pilots. On 21 July, with international tensions mounting, he and several other stars of the pre-war aviation circuit had met with Jacques Mortane. ‘If only they’d listened to us and consulted us in peacetime we’d be completely au fait with military aviation by now,’ argued Garros. ‘We could have been extremely useful. Instead we’ll have to start from scratch.’

One vital area of operations was aerial reconnaissance. Despite the lessons of pre-war manoeuvres, peacetime opportunities to rehearse observation skills had been few, compelling aviators and army staffs alike to learn on active service. In consequence, aerial reconnaissance had little impact during the battle of the Frontiers. Staff officers struggled to coordinate the activities of their squadrons, leaving much to individual initiative, and lacked confidence in the often conflicting and fragmentary reports produced by pilots battling to identify the enemy below. ‘The movements reported by our pilots do not allow us to conclude the enemy offensive has begun,’ opined Joffre, at news of enemy soldiers marching through Belgium in unexpected strength and of large troop concentrations in the Ardennes.

In Alsace the six squadrons attached to First Army remained underused in difficult terrain, while in the Ardennes Third and Fourth Armies simply blundered into the advancing Germans and were badly mauled. Brindejonc des Moulinais (DO22), by now a corporal, could find no sign of the enemy on a reconnaissance flight on 17 August, and it was another five days before he finally spotted a battle line: ‘[It] seemed to run between Virton and Robelmont. Towards Rossignol we caught sight of a long column of cavalry coming out of a forest. The mist was hampering us a little but we could still make out all the twists and turns of the firing line.’ Sadly, his sighting was too little, too late: the battle line belonged to 3rd Colonial Infantry Division, marching to near-annihilation. At Morhange in Lorraine Captain Paul Armengaud (HF1) managed to give warning of German intentions: ‘I could see all the guns behind the revetments, the lines of trenches, the abatis in the woods, the hidden reserves; it had every appearance of a trap set for our army and the left of the neighbouring army.’ However, GQG simply refused to believe him: Second Army duly advanced and was repulsed with heavy losses.

Sergeant Eugène Gilbert (MS23/MS49) focused on the army’s failure to practise cooperation work. ‘We made a big mistake by not thinking about aircraft working in tandem with the other arms,’ he insisted in July. ‘Our soldiers aren’t familiar with us and mistakes over aircraft nationality are inevitable. We should have established an aviation element within each army corps and had them perform joint exercises.’ Gilbert’s fears were soon vindicated. Although French aircraft were clearly designated with their red, white and blue roundels, aeroplanes were such a novelty that most ground troops mistrusted any machine flying over their heads, whatever its markings. The long, hot retreat that succeeded the battle of the Frontiers brought a member of 119th Infantry close to Esternay: ‘We were following a narrow road that zigzagged across a broad plain. Far ahead, the column was painfully strung out, and several stragglers were cutting across the fields to rejoin their units. Our section was in pretty good shape and had fallen in behind to scoop them up. Just then an aeroplane … passed some 200 to 300 metres over our heads. French or German? A roundel or a cross? Difficult to tell. But a couple of men ahead of us stopped and fired in the air like a hunting party shooting at pigeon or partridge. Nevertheless the plane carried on south and disappeared from view behind the nearest hill. A few hours later – when we were all back with the column – we passed a group of soldiers loading a plane, minus its wings, on to a big lorry. An adjudant stood alongside it, at the edge of the road. He had his arm in a sling and we regarded him with interest as we passed by. “Quite so!” he shouted, quite without rancour. “Take a good look, you set of ***! You almost did for me there. Try not to mistake me for a Boche next time.”’

The same evening an order arrived expressly prohibiting ‘firing on [our] aeroplanes’ – to little avail. ‘Our troops are still firing up at us whenever we fly over them,’ complained Lieutenant Alfred Zapelli (D6) on 4 September. The following day he decided further action was needed. ‘I’ve had my roundels repainted four times bigger,’ he claimed. ‘[Now they’re] 2 metres wide.’

French aircraft were performing little better as artillery spotters, a point rammed home to one group of resentful airmen by General Franchet d’Espèrey, the newly appointed commander of Fifth Army: ‘[The general said] our results have been fine from a strategic point of view, but tactically we’re lagging a long way behind the Germans because they’re so good at artillery spotting,’ noted one pilot in his diary on 3 September. ‘Then … [he] spouted some nonsense about the way the Germans adjust their fire (two aircraft crossing over the target). Most of us are only here to fly reconnaissance missions. It’s not our fault if the rest of the squadrons aren’t up to the mark. Blame the brass-hats. They don’t believe [in aviation] so they don’t give us enough support. And they’re not willing to learn how to use us to best advantage.’

In the fortress city of Montmédy, a group of hard-pressed artillerymen would certainly have backed the general. Around 3.00 pm on 23 August one of their officers was heartened by the arrival of three French planes: ‘A bit late, but an opportunity not to be missed. I went looking for one of the pilots. Sadly, their machines weren’t powerful enough to carry an observer. So be it. But the [pilots] swore that if required they’d be back the following day in armoured two-seaters. On that note, off they sauntered.’ Two days later, with no sign of the promised spotters, the officer turned in despair to the governor of Montmédy: ‘I asked him to call Stenay. Could he get them to send a machine capable of carrying an observer and a pilot, emphasizing this last point in particular? About two hours later, much to our delight, a French biplane appeared. I hurried over to say hello. “Can you carry an observer?” [I asked]. “No,” [came the reply], “the squadron only has single-seaters.” What a let-down! I was sorry to have brought this poor pilot on a wild goose chase, but I’m starting to understand why we see so few French planes. There can’t be that many to start with and they must all be occupied on long-range reconnaissance duties. We can’t have enough left over to spot for the artillery like the Germans.’

Flying his Dorand DO.1 over Luxembourg, Corporal Brindejonc des Moulinais was feeling very jumpy: ‘I was gripped by a crazy desire to get away, to make a rapid turn back towards the airfield. Honestly, anyone who’s ever experienced the sensation that thousands of pairs of eyes are following you, thousands of rifles pointing at you, while bullets clatter past, sometimes hitting a wire or a rib, will understand what I’m talking about, and why I might have been feeling on edge. Then the artillery joined in.’ Sergeant Lucien Finck (HF7) knew exactly what he planned to do if he came under fire: ‘Several pilots had persuaded me that you can’t be hit at 1,200 metres. The Moroccan campaign [1911–12] had proved it. Suitably reassured, I took off with every confidence. I climbed to 600 metres over Verdun and headed straight for my target. At 1,200 metres over Conflans, I realized my mentors might have been better advised first to acquaint themselves with our front. Rifle and machine-gun fire surrounded me on all sides. It all looked pretty chancy.’

Finck struggled up to 1,800 metres, where he found ‘things pretty quiet apart from the odd shell’. But even then he didn’t quite have the skies to himself, seconds later spotting ‘a German that very politely drew aside to let us pass’. And he quickly discovered that altitude could pose its own problems. ‘My engine cut out at 1,800 metres,’ he reported on 10 August. ‘I dived to 1,200 metres to stop my propeller jamming. My Gnôme [engine] started up again as soon as I pulled back on the throttle. Condensation in the carburettor had formed two blocks of ice in the air intakes.’

Sergeant Auguste Métairie was serving with the Camp Retranché de Paris (CRP), the Paris garrison, under the command of General Gallieni: ‘Our machines afforded us no more than relative safety, very relative indeed. The lines changed completely from one day to the next, so we had no idea where the opposing sides were. You had to keep your eyes open all the time. We were operating at altitudes which seem risible today, starting our reconnaissance missions at 2,000 metres and ending somewhere between 1,100 and 1,500 metres. Luckily, the Germans were lousy shots.’

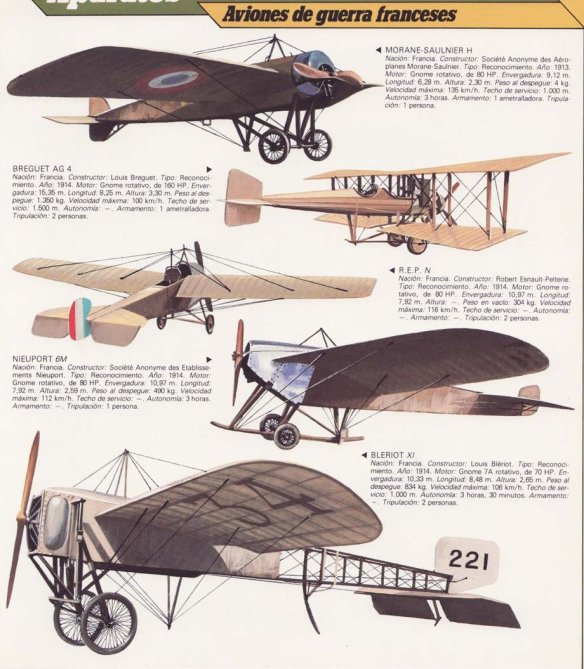

Métairie and his squadron were equipped with the Farman HF.20, whose ‘pusher’ configuration, with the engine behind the pilot, gave the crew a good field of vision over the countryside below. On 2 September, with the French in full retreat across the Marne, Gallieni ordered six reconnaissance sorties. One plane turned back with engine trouble, but four all spotted German columns moving south. The sixth and last sortie was flown by a 160hp Gnôme-powered Breguet AG.4, piloted by the aircraft’s designer and manufacturer Corporal Louis Breguet, with balloon officer Lieutenant André Wateau as his observer. They left the airfield at Vélizy at 3.30 pm. ‘Groups of cavalry and infantry moving … through the Automne valley,’ they reported. ‘Spotted fires in the forest of Compiègne … Saw nothing in the Ourcq valley.’ It seemed to Wateau that the German armies were turning south-east, away from Paris.

From their base at Écouen REP15 and MF16, the two squadrons attached to General Maunoury’s Sixth Army, were scouring the same area. At 8.00 am on 4 September Lieutenant Émile Prot (MF16) and his observer, Lieutenant Edmond Hugel, set off in fine weather in search of the German advance guard, expecting to find it moving south-west towards Paris. ‘To my utter astonishment, the road [between Nanteuil-le-Haudouin and Gonesse] was completely empty,’ noted Prot. ‘First German troops [spotted] at Nanteuil. They had passed the village but were [further east] close to the Brégy–Meaux road. The advance guard was over towards Sennevières. Lots of movement on the Nanteuil–Crépy and Nanteuil–Lévignen roads. Troops resting. Parks of all kinds. Apparently some kind of logjam. Another column at Lévignen; the head of the column already entering Betz.’

Prot and Hugel had confirmed Wateau’s findings. So too did further sorties flown the following day: von Kluck’s First Army had definitely swung away from Paris. However, the staff of Sixth Army had little confidence in their squadrons. Arriving hotfoot from Alsace, aviation commander Captain Georges Bellenger had received a brusque welcome from the chief of staff, Colonel Guillemin: ‘I can’t be bothered wasting my time with pilots,’ barked the colonel. ‘They’re nothing but ill-disciplined acrobats.’ Unfortunately, some of the reports produced by Bellenger’s crews had been confused and contradictory, and Major Duthilleul, the head of intelligence, refused to believe any of them.

‘The enemy columns march by while VI Army washes its linen in rivers all over the region,’ fumed Prot. ‘I went to [HQ at] Le Raincy to make my report. Pointed out a flank guard, its exact position mapped from first to last.’

Duthilleul had dismissed it as nothing more than an outpost line.

‘They’re not outposts,’ insisted the horrified pilot. ‘They’re whole columns.’

‘My men are despondent,’ reported Bellenger on 6 September. ‘They’re performing their duties half-heartedly and I no longer dare exceed my orders.’ However, by quietly slipping the relevant reports to his CRP counterpart and a British liaison officer, the feisty Bellenger had made sure the crucial information reached General Gallieni. Sixth Army was ordered to attack the German flank and the mood was transformed: ‘The faces of my aviators lit up at the news and this time they took off full of vim.’

Auguste Métairie (CRP) soon had a narrow escape: ‘My mission was to fly as far as Lizy-sur-Ourcq and reconnoitre the battlefield. It was all so strange and confusing that – I admit – I began to dawdle…. Everything was on fire. Eventually I stumbled across the heart of the battle. It affected me badly [and] I stopped checking my watch. Suddenly the engine started missing, then nothing. It was dead. Out of fuel. Damn it! Was I going to end up in the hands of the Boches? Ahead I could make out Meaux [and] to my right the Eiffel Tower. I had to descend. Between 1,800 and 1,600 metres I was very apprehensive. I couldn’t even summon up any sympathy for the burning villages. All I could think about was myself.’ Then Métairie spotted a Maurice Farman spiralling down. Was the pilot crazy? Or could it be a captured machine? Métairie followed the plane down and quickly realized the troops below were French: ‘What a sight for sore eyes! Everything’s fine! I can see some red monoplanes: they’re REPs, they’re French. I won’t be taken prisoner [after all].’ He landed, begged a little petrol and eventually flew home as calmly as possible.

On 8 September, near Triaucourt-en-Argonne at the eastern end of the battle line, information provided by two French spotters – one piloted by Lieutenant René Roeckel of HF7, accompanied by Lieutenant Mingal of 46th Artillery, and the other by Sergeant Joseph Chatelain – brought Third Army a significant success which finally persuaded GQG that aviation might have a role to play. ‘I helped our artillery destroy half the German batteries opposite,’ wrote Roeckel. ‘I carefully reconnoitred the enemy guns in the morning before directing our fire upon them. Then I had the pleasure of watching from the air as the shells from our 75s fell among the German batteries. We destroyed two caissons in under a minute. People can talk of nothing else.’ Two days later Roeckel was back in action, this time directing artillery fire on to enemy columns around Vaux-Marie, with heavy casualties again the result.