Leutnant zur See Otto Mieth wrote an article that evocatively described the last operational flight of L-48, originally published in German in Frankfurter Zeitung Illustriertes Blatt on 28 February 1926 translated into Shot Down by the British, it was published in The Living Age on 17 April, 1926:

16 June 1917 was a bright beautiful summer day. Our naval airbase, Nordholz, near Cuxhaven, lay embosomed in idyllic heath country and amid clumps of pines and birches. Its gigantic sheds and grounds basked in the sunshine as if there were nothing but peace and goodwill on earth. Suddenly a wild, warlike shriek, beginning with a deep rumple and rising into a long, shrill tremolo, rent the dreamy atmosphere. Thrice did the siren call.

Thus Mars suddenly strode into the tents of peace, for this was the summons for a raid against England. Files of attendants rushed out of the barracks to the airship sheds, whose doors suddenly yawned wide open as if they had been burst out by the rising roar of the motorists within. A moment later two giant Zeppelins slowly emerged. One was L.48, the newest airship in the navy, to which I had been assigned as watch officer.

As I directed the operation of bringing her out, I studied with proud delight the slender, handsome lines of the giant, six hundred feet long and sixty feet through at its greatest girth. Four gondolas, one on either side, and one fore and one aft in the centre, were suspended below its body. They contained five motors, while the front gondola was reserved for the steersmen and their instruments. Our regular crew consisted of twenty men, including two officers, but today we carried an attack commander, Captain Sch— [Korvetten- Kapitän Viktor Schuetze].

Black is the colour of night and black was the colour of our ship. Our shield was darkness, for when she enwrapped the earth and nature and man on moonless nights she announced the hour for us to rise to lofty altitudes and to attack the enemy behind his ancient walls of water.

We did not look forward expectantly to the devastation we planned to wreak. That was in the line of duty, for which we risked our lives. But the real joy in our service was, after all, the charm of nature, the sense of isolation in infinite space for our fragile ship – alone with the heavens above and the waters beneath the earth.

As soon as I boarded the ship, our mooring lines were loosened, propellers began to whirl and the L.48 rose quickly but majestically into the air. A last wave of the hand, a shout of ‘Back tomorrow!’ and the North Sea rolled beneath us.

Our course lay due west. We were in the best of spirits and though our sailors were superstitious, no-one recalled the fact that this was our thirteenth raid. Our sealed orders were opened. They read briefly: ‘Attack South East England – if possible London.’ Willhelmshaven appeared on our port side. The vessels of our high sea fleet, lying on watch at Schillig Reede, signalled, ‘A successful trip.’

The North Friesland Islands came into sight and disappeared behind us. We pushed steadily onward. Slowly the homeland sank into the misty distance and over Terschelling we found ourselves already in the enemy zone of operation. Only a few days before, the British had surprised and destroyed two of our reconnoitring airships at this point. We rose to the three thousand metre level scanning the air anxiously in all directions but discovered no sign of the enemy.

On and on. Our motors hummed rhythmically, our propellers whistled. It gradually became darker. The last rays of the sun gilded the waves and a light mist spread like a thin veil over the earth making it difficult to pick up our bearings. We had gradually risen to five thousand metres and were close to the southeatern coast of England. But it was still too light for our purpose, so we were forced to bear away from land and wait for darkness. Suddenly a heavy thunder storm swept over England. Flashes of lightning a kilometre long rent the clouds. This wonderful scene lasted but a few minutes and then passed on but then we resumed our course we discovered that there had been a violent atmospheric disturbance and that the direction of the wind had suddenly changed and we were bucking a strong southwest gale that impeded our progress. By this time it was perfectly dark and we crossed the English coast in the vicinity of Harwich. Silver-white streaks of surf were clearly visible beneath us, so that we could easily follow the contours of the coast. But everything else was absolute blackness; not a light was visible.

We knew, therefore, that an alarm had been. Millions of people were aware of our coming and were preparing to give us a warm reception. We made our last preparations. Signals rang through the ship, ‘Full speed ahead,’ ‘Clear ship for battle.’ Now for the luck of war!

By this time it was bitterly cold, the temperature having fallen seventy-two degrees since we left Germany and we shivered even in our heavy clothing. At our high altitude, moreover, we breathed with great difficulty and in spite of our oxygen flasks several members of the crew became unconscious. Nevertheless we pushed on steadily against the southwest wind, driving our machines at their full power. But June nights are short in England and our chances of reaching London grew constantly less. Suddenly a starboard propeller stopped and an engineer reported that the motor had broken down.

As our forward motor was knocking badly, we had to give up London. Thereupon one bit of bad luck followed another. Our compass froze and we had great difficulty in keeping our bearings. At length we decided to attack Harwich, which lay diagonally ahead of us wrapped in a light stratum of fog so we made for the leeward side of the town in order to cross over quickly with the wind behind us. It was 2.00am and our altitude was 5600 metres, or nearly eighteen thousand feet.

When we swung around and pointed directly for Harwich it was still as death in the gondola. All nerves were tense. The only sounds that broke the silence were low orders to the steersman from time to time. Suddenly somebody work up below us. Twenty or thirty searchlights flashed out in unison, thrusting long, white groping, luminous arms into the air. They clutched hastily and nervously, crossed each other, passed so close to us that our gondola was as bright as day. Yes, they even flickered across the ship itself without detecting us. Meanwhile we drew closer and closer to our goal, sliding between the shafts of light with humming propellers. For several minutes this game continued. Then one searcher picked us up and held us fast in his circle of light. Thirty white arms grasped greedily at us as if they would tear us out of the air with their eager clutches. Our slender black ship was flooded with their radiance, which it reflected in jetty sparkles from its glittering body. Instantly it began to thunder and lighten below as if all inferno had been let loose. Hundreds of guns fired simultaneously, their flashes twinkling like fireflies in the blackness beneath. Shells whizzed past and exploded. Sharpnel flew. The ship was enveloped in a cloud of gas, smoke and flying missiles. Hissing like poisonous serpents, whistling, howling, visible during their whole trajectory, blue-white uncanny fire-shells and rockets sang past us. Peng! peng! bellowed the English guns in their sharp staccato, like a great pack of hounds at the heels of a stag. But we kept steadily forward into this witches’ cauldron. Every man stood at his post with bated breath. The weariness, the cold and the rarefied air had been forgotten. Our beating hearts fairly drummed against our sides. I kept my eye glued on my vertical glass, my right hand on the lever of the electric bomb-release. Gradually our target came into the field of vision until it reached the point set. I pressed the lever and at fixed intervals, one by one, the bombs fell. A new sound now punctuated the incessant roar beneath – the dull throbbing boom! boom! as our missiles struck the earth. The whole thing lasted only a minute or two, but in that brief interval was concentrated the experience of an ordinary lifetime. We steered straight ahead across the area of fire. To be or not to be was now the question. Were a single one of the countless shells that flew past us to strike our six hundred feet of unprotected body, our gas would be aflame in an instant and our fate would be sealed.

It seemed a miracle that we ever emerged from the tumult. The firing got weaker and at length ceased. The searchlights were extinguished. Night embraced us again and covered also the land with its opaque blanket. Only dull-red glowing spots far behind us marked the points where our bombs had started conflagrations.

It was half past two and from our altitude the pale glow of England’s midsummer dawn was already visible. So it was high time to get back over the open sea, for one there our principle danger would be over. But our frozen compass was our undoing. Instead of steering to the east, we inadvertently headed towards the north and before we discovered our error we had lost valuable time. Added to that, our forward motor also failed us, so that our speed was sensibly diminished.

I had just returned to my station after dispatching a radiogram reporting the success of our raid and was talking with Captain Sch—, when a bright light flooded our gondola, as if another searchlight had picked us up. Assuming that we were over the sea, I imagined for an instant that it must come from an enemy war-vessel but when I glanced up from my position, six or eight feet below the body of the ship, I saw that she was on fire. Almost instantly our six hundred feet of hydrogen were ablaze. Dancing, lambent flames licked ravenously at her quickly bared skeleton, which seemed to grin jeeringly at us from the sea of light. So it was all over. I could hardly credit it for an instant. I threw off my overcoat and shouted to Captain Sch— to do the same, thinking that if we fell into the sea we might save ourselves swimming. It was a silly idea, of course, for we had no chance of surviving. Captain Sch— realised this. Standing calm and motionless, he fixed his eyes for a moment upon the flames above, staring death steadfastly in the face. Then, as if bidding me farewell he turned and said ‘It’s all over.’

After that, absolute silence reigned in the gondola. Only the roar of the flames was audible. Not a man had left his post. Everyone stood waiting for the great experience – the end. This lasted several seconds. The vessel kept an even keel. We had time to think over our situation. The quickest death would be the best; to be burned alive was horrible. So I sprang to one of the side windows of the gondola to jump out. Just at that moment a frightful shudder shot through the burning skeleton and the ship gave a convulsion like the bound of a horse when shot. The gondola struts broke with a snap and the skeleton collapsed with a series of crashes like the smashing of a huge window. As our gondola swung over we fell backward and somewhat away from the flames. I found myself projected into a corner with others on top of me. The gondola was now grinding against the skeleton, which had assumed a vertical position and was falling like a projectile toward the earth. Flames and gas poured over us as we lay there in a heap. It grew fearfully hot. I felt flames against my face and heard groans. I wrapped my arms around my head to protect it from the scorching flames, hoping the end would come quickly. That was the last I remember.

Our vessel fell perpendicularly, descending like a mighty column of fire through the darkness and striking stern first. There was a tremendous concussion when we hit the earth. It must have shocked me back to consciousness for a moment for I remember a thrill of horror as I opened my eyes and saw myself surrounded by a sea of flames and red hot metal beams and braces that seemed about to crush me. Then I lost consciousness a second time and did not recover until the sun was already high in the heavens.

Gradually I collected my thoughts. How did I get here in these strange surroundings on this litter? It was like a dream. I half raised myself painfully and saw that my legs were wound in thick, bloody bandages. I could hardly move them, for they were broken. Then I made a new discovery, my head and legs were covered in burns, my hands were lacerated and when I breathed I felt as if a knife were thrust into me. I thought to myself ‘Am I dreaming or awake?’ Just then a human voice interrupted my groping thoughts: ‘Do you want a cigarette?’ And a Tommy stuck a cigarette case under my nose with a friendly grin. So it was no dream. I was a prisoner.

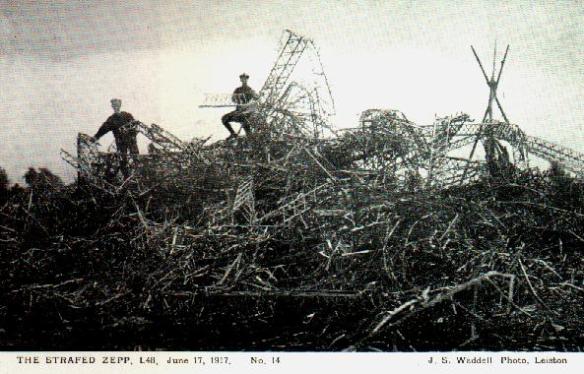

I now learned what had happened. An English aviator had crept up on us unobserved and had managed to fire our ship. We fell in an open field near Ipswich. All our crew were killed except myself and two subordinate officers, one of whom died later from his wounds. The other was in one of the side gondolas, which chanced to be out of reach of the flames and though he became unconscious for a moment he was not injured. The moment we struck ground he clambered out and ran away as if the Furies were after him but a person must be excused for losing his head under such circumstances. I have never been able to understand just how I personally escaped. Probably my comrades who fell on top of me when the ship settled aft shielded me from the flames, for I was not seriously, even though painfully, burned. When we struck, stern foremost, the light skeleton of the long vessel telescoped and this broke my fall and the prow stood upright above the debris, so that I was not hit by flying beams.

When I asked how my English captors found me, they said they heard me groaning and were able to pull me out of the flames before it was too late. I soon recovered from my shock and wounds, survived my long imprisonment and have even become accustomed to having everyone who meets me, who knows of my experience inquire solicitously, ‘ Do you feel any bad effects?’