Despite having waged a series of small wars throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the opening of WWII caught the Italians unprepared militarily. Mussolini’s advisors had estimated that Italy could not possibly be prepared for major military operations until 1942, and the Italo-German negotiations for the Pact of Steel had stipulated that neither signatory was to make war without the other earlier than 1943. Although considered a great power at the time, the Italian industrial sector was relatively weak compared to other European powers. The Italian Royal Army (Regio Esercito) was comparatively weak at the commencement of the war. Italian tanks were of poor quality, radio communications were spotty, and the bulk of Italian artillery dated to the previous war. Italian authorities were acutely aware of the need to modernize and were taking steps to do so. Almost 40% of Italy’s 1939 budget was allocated to military spending. The Italians remained non-belligerants until June 1940, but their efforts should not be discounted—especially with respect to their air arm.

Since 1923, the Italian Air Force (Regia Aeronautica) had been praised as the quintessential Fascist service, and Mussolini banked on his air power to overcome Italy’s strategic and economic confinement. Italy, along with Japan and Germany, had begun its arms race by producing a new generation of warplanes. Through these means, the Axis Powers began WWII with highly competent air forces designed around some of the best airplanes in the world. In their theory of aerial warfare and in the organization of their air forces, the Italians initially seemed much further advanced than the Japanese or the Germans. The Italians were also pioneers in the use of armored cars and self-propelled guns, and their Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tank weapons were equally effective and as deadly as the infamous German 88s.

Mussolini had hoped that the Italian Air Force, with its approximately 2,600 aircraft, would prove a dominating factor in control of the airspace over the Mediterranean. The hope was not completely fulfilled because Italy’s aircraft industry proved particularly unequal to the demands of large-scale wartime production. The Italians began the war with no aircraft carriers, although they attempted to build some. Converted from a passenger liner, the Aquila, a carrier was begun in late 1941 at the Ansaldo shipyard in Genoa and continued for two years. It was unfinished when the Italians surrendered in 1943. Nonetheless, the Italian peninsula and the many Italian-held islands in the Mediterranean served them as permanent airbases for over-water operations.

Despite its lack of aircraft carriers, the Italian navy and air forces succeeded in fulfilling their two wartime objectives: preventing the Allies from severing Italy’s maritime supply routes to Axis forces in North Africa and maintaining themselves as viable “fleets in being” thereby requiring the Allies to expend scarce resources as a defense against them. Although Britain’s Royal Navy operated up to eight of its twelve aircraft carriers (1939) in the Mediterranean at varying times during the war, they utterly failed to achieve any decisive or long-lasting results in terms of halting the flow of supplies to North Africa largely because of the Italians.

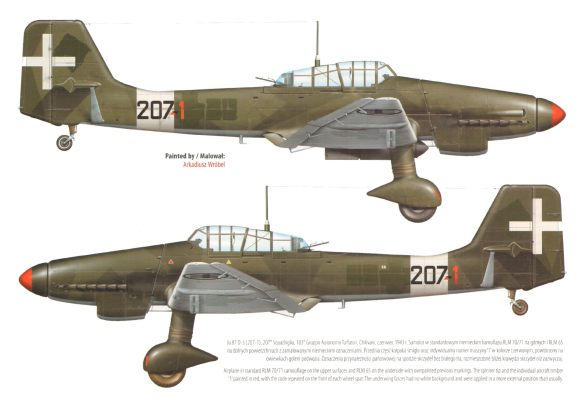

In 1939, the Italian government asked the Germans to supply 100 Ju-87s, and Italian pilots were sent to Austria to be trained on dive-bombing aircraft. In the spring of 1940, Ju-87 B-1s, some of them ex-Luftwaffe aircraft, were delivered to the Italian 96th, 100th, and 101st Bombardment Groups who flew them into 1942. Some of the Stukas, renamed Picchiatelli saw action in the Italian invasion of Greece in October 1940, against the island of Malta, and against Tobruk in North Africa.

In November 1940, as part of the Battle of Britain, two hundred Italian planes of the Corpo Aereo Italiano had flown the Channel in a daylight raid on Harwich Naval Base, England. Three RAF squadrons intercepted and brought down eight bombers and five fighters. One bomber and five Italian fighters were damaged. There were no RAF losses. The raid had consisted of a formation of Italian Sparviero bombers at 12,000 ft escorted by CR-42 fighters, which were biplanes. In purely technical terms, these were outclassed by more modern monoplanes, but this was not always the case in practice. Although Luftwaffe aircraft had difficulty flying in formation with the slower biplanes, the CR-42 Falcos could easily out-turn Hurricanes and Spitfires, making the Fiats more difficult to hit. A few days later, the Italians attacked a convoy, and for four nights running they dropped bombs on Harwich and Ipswich. Thought to be more of a hindrance than an asset, however, Hitler demanded that the Corpo Aereo Italiano be withdrawn to serve in Belgium. Italy’s over-the-Channel air war was over. Worse still, by early 1941, the Italian air force in Libya announced that it had lost nearly 700 aircraft.

Also, in late 1940, the Greeks broke through the Italian lines in Macedonia and seized the important town of Pogradec in Albania. It was important that the Axis deny land-bomber bases to the RAF in the region within range of the critical oilfields at Ploieste. Greek forces in Albania took city after city, thereafter, despite having inadequate supplies and facing a supposed Italian air superiority. By mid-January 1941, Greek forces occupied a quarter of Albania. The Italian troops were driven backwards toward ports jammed with equipment and reinforcements. It all had the look of an Italian Dunkirk. Preparing for the worst by the construction of a defensive wall in front of the ports of Valona and Tirana, only almost arctic weather conditions and rugged terrain came to the rescue stalling a Greek offensive before it could shatter the Italian lines and push them into the Adriatic. In an attempt to restore Italian prestige before German intervention was needed, an Italian counterattack was launched in March under Mussolini’s personal supervision. The attack failed, and both sides settled down to a war of attrition. The Italian failure caused Hitler to delay Operation Barbarossa, his planned attack on the Soviets.

A disconnect seemingly existed between Mussolini’s strategic vision for the Italian air force and the technical capabilities of its planes. When the war broke out Italian models were found wanting in up-to-date military equipment. High-altitude bombing proved ineffective over Malta and North Africa, the fault of rudimentary bombsights and a lack of radio contact between pilot and bombardier. Although having forged ahead with torpedo-bomber designs and models, the Italians had not formed combat units that contained them. Moreover, they lacked their own dive-bombers like the German Stuka largely because of the air philosophy laid out by Italian General Giulio Douhet, a contemporary of Billy Mitchell, who emphasized the destruction of enemy cities and industrial ports through level-bombing from the air.