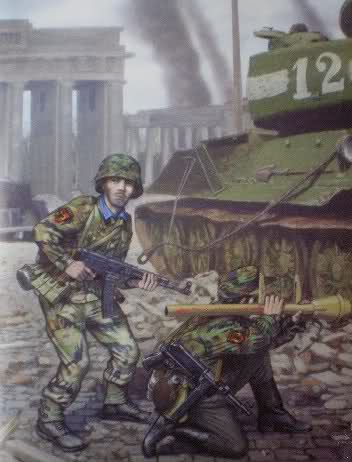

“Einheit Ezquerra”, Berlín 1945.

The Nazis, scrambling to find more soldiers, by D-Day had recruited 450 Spaniards to serve in the Waffen-SS. Spanish diplomats in Germany warned Madrid about this recruitment effort repeatedly during the summer of 1944, but despite Spanish protests, German officials in Madrid claimed ignorance of the matter or an inability to do anything about it. While most recruits were Spaniards already living in Nazi-occupied Europe, to these must be added the 150 Spaniards who crossed into France in June and July 1944.

The Spanish soldiers who had joined the Waffen-SS and other German military units fought most extensively on the Eastern Front, but also in the Balkans, against the Resistance in France, and in the final defense of Berlin in 1945. It is difficult to estimate the numbers of Spanish veterans of the Blue Division who served in the Waffen-SS because German records of these enlistments are scarce. We can say something about the potential manpower pool, however; of the over 40,000 Spaniards who served in the Blue Division and Legion, slightly under 400, excluding casualties, known deserters, and those captured by the Soviet Union, did not return to Spain at the end of their tours of duty on the Eastern Front. Of these, 34 were officers (only one of whom was over the rank of captain), 139 were noncommissioned officers, and 210 were soldiers at the rank of corporal or below. Although exact numbers are unavailable, the best estimate puts the number of these Spaniards who fought in the military and security forces of the Third Reich after June 1944 at just under 1,000.

One Spaniard who established a clear and indisputable record within the SS was Rufino Luis Garcia-Valdajos. Born in 1918, he enlisted in the Blue Division in late 1942, remaining as a volunteer until March 1944, when he remained in Germany rather than be repatriated to Spain. He gained a position with the SD in Paris and worked against the French Resistance until the Nazi retreat forced him to return to Germany in late 1944. There he joined Belgian collaborator Leon Degrelle’s SS-Freiwilligen-Grenadierdivision-Wallonie (SS Wallonian Volunteer Grenadier Division) in November 1944. In February 1945, Garcia-Valdajos, now an SS first lieutenant, applied to the SS Rasse- und Siedlungshauptamt (RuSHA, Central Office for Race and Resettlement) for permission to marry a German woman living in Berlin, Ursula Jutta-Maria Turcke. After determining that neither Garcia-Valdajos nor his bride had any Jewish ancestry, this permission was granted.

While the case of Garcia-Valdajos is better documented than most because of his request to marry a German, he was not alone in his enlistment. Many of those who left home to enlist in the German army and Waffen- SS were very young, some still in their teens, who essentially ran away from home to sign up with the Germans, much to the consternation of the Franco regime. The Spanish government’s attempts to lobby the German government for the return of these men and boys were unsuccessful. As Franco’s ambassador in Berlin informed the Spanish Foreign Ministry, Berlin was unlikely to surrender precious laborers and soldiers to an increasingly unfriendly Madrid, especially as these were volunteers who in many cases did not want to return to Spain.

The Allies protested strongly to the Spanish Foreign Ministry about these enlistments in German military and intelligence services. Of particular concern to the United States and the Free French representative in Madrid was the alleged service in the Gestapo of dozens of Spaniards in France and rumors that hundreds more were preparing to join them. The Spanish Foreign Ministry vehemently denied knowledge of any enlistment or service in the German military, indicating that perhaps these soldiers and agents might be Spanish expatriate communists who, for “the spirit of adventure and economic necessity,” might have enlisted. In any case, the Spanish government asserted, their numbers could not compare with those of Spaniards enlisting in the ranks of the Allies. According to the Spanish foreign minister, the Spanish government had not and would not authorize the enlistment of Spaniards, Blue Division veterans or not, in German military, security, or police forces, nor allow them to aid German forces in France. The foreign minister did, however, admit knowledge of the many Spaniards who had joined the French Resistance or were fighting for the Allies in Northern Italy. Despite these enlistment on both sides, he declared that Spain would not deviate from its “strict neutrality.”

The Spanish Foreign Ministry, despite its statements to the Allies, had extensive knowledge about the illegal service of Spaniards in the Gestapo, Waffen-SS, and Wehrmacht. As early as the spring of 1944, the Spanish Foreign Ministry had confirmed reports from its European embassies that Spaniards were enlisting in German military and intelligence services. This information came, in its most direct form, from Spanish veterans of German service, who began to show up at Spanish legations, consulates, and embassies throughout Europe in early 1944. Often destitute, they told of service in the Balkans, France, and the Eastern Front. While many claimed to have served in the German army, most had worn the uniform of the Waffen-SS.

The Foreign Ministry was also well aware that recruitment of Spaniards occurred in Spain as well as in Nazi-occupied Europe. The Deutsche Arbeitsfront-DAF (German Labor Front) office in Madrid, which formerly had contracted workers openly, was responsible for much of this recruitment, providing papers, funds, and directions to Spaniards wishing to enlist in the Nazi cause. The Spanish Foreign Ministry also suspected that elements of the Falange were aiding Nazi recruitment efforts. In August 1944 one of the foreign minister’s deputies sent a letter to Falangist secretary-general Jose Luis Arrese, asking if the party knew anything about a group of 400 young falangistas allegedly preparing to leave Spain for France to join German occupation forces there. For the Spanish government to publicly admit knowledge of Spanish volunteers would have meant admitting it was unable to stop these clandestine activities, however. Franco may also have feared Allied retaliation.

After the dissolution of the Blue Legion, Spaniards served in different units of the German armed forces. Most served in two companies (the 101st and 102d) of a unit in the Waffen-SS, the Spanische Freiwilligen Einheit

(Spanish Volunteer Unit), which recruited from Spanish workers in Germany, veterans of the Blue Division, and a few adventurers who had crossed illegally from Spain into German-held France. Others served with Leon Degrelle’s SS Division, incorporated into the organization as the 3d Spanish Company of the 1st Battalion. The Belgian unit found it easy to recruit Spaniards from those already serving in Germany, as most Iberians found the Prussian discipline of the Wehrmacht too strict and humorless for their “Latin temperaments.”

Throughout the rest of the shrinking Nazi empire, other small units of Spaniards were organized in late 1944 to fight against the Allies in northern Italy, near Potsdam, on the Franco-German border, and elsewhere. The unit in Italy, under the command of a Lieutenant Ortiz, fought against partisans in northern Italy and Yugoslavia. Unlike other Spanish units, it gained a mixed reputation, with accusations of looting, rape, and plunder. Other Spaniards claimed to have served with Otto Skorzeny’s commando unit in the Battle of the Bulge.

One of these units, the 101st Company of Spanish Volunteers, fought a desperate rearguard action near Vatra-Dornei, Romania, defending the Carpathian mountain passes against the Red Army. Led by a German officer, this unit contained some 200 men, mostly veterans of the Blue Division and the Spanish labor force in Germany. During the last half of August 1944, these Spaniards fought doggedly until the defection of Romania on 27 August. Turning their backs to the advancing Soviets, on 31 August what was left of the 101st began a slow retreat northwest. Fighting against attacks from both Soviet forces and Romanian guerrillas, deserted by the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS, the unit was caught between Soviet armies in Hungary and Romania. At the end of October, the few dozen survivors of the unit finally reached Austria. The 101st and its parallel unit, the 102d, were quartered together in Stockerau and Hollabrunn, north of Vienna. The 102d had fought Tito’s Yugoslav Partisans in Slovenia and Croatia during the summer of 1944, where it was as mangled as the 101st. All of these units also suffered from desertions, as individuals and small groups fled the front lines to seek what they hoped would be safety in the hands of the Allies or in the interior of Germany.

Miguel Ezquerra, a veteran of the Blue Division and then a captain in the Waffen-SS, led another small unit into the Battle of the Bulge. He and his men previously had served German counterintelligence in France, fighting against Spanish exiles in the Resistance. Later called the Einheit Ezquerra (Ezquerra Unit), this formation was closely linked to General Wilhelm Faupel, former German Ambassador to Spain, and his Ibero- American Institute, a research center in Berlin that promoted closer Hispano-German and Nazi-Falangist ties. In January 1945, Ezquerra was commissioned to enlist all the Spaniards he could find into one unit, which he would command as a Waffen-SS major. These enlistments greatly troubled the Spanish government, which viewed with alarm news of Spaniards serving in the SS and other Nazi organizations. Apart from the dangers confronting these men, the Franco regime was concerned that they were still wearing the emblem of the Blue Division, a shield with the colors of the Spanish flag, and the word word “Espana” on their uniforms, an obvious and visible compromise of Spanish neutrality. Franco ordered his diplomats remaining in Germany to dissuade Spanish workers from joining the Waffen-SS or German armed forces, but despite the dramatic changes in the European situation, as late as October 1944 some volunteers were still petitioning to be sent to work in Germany.

Even the Ibero-American Institute, long a stalwart ally, had turned against the Spanish party. Still under the direction of General Faupel, in early 1944 the Institute had taken over the publication of Enlace (Liaison), a newspaper for Spanish workers in Germany published by the Spanish embassy in Berlin from mid-1941 to late 1943. Faupel had gained control over the newspaper by paying its debts to the German government. Edited under Faupel’s direction by Martin Arrizubieta, a defrocked Spanish Basque priest and former Republican captain in the Spanish Civil War, the newspaper took on a decidedly anti-Francoist bent in the fall of 1944. Promoting a strange mixture of Nazism and Basque separatism, the paper, continuing under its old title, produced a great deal of confusion among the remaining members of the Spanish colony in Germany. Claiming to be both Falangist and National Socialist, the paper insisted that “the salvation of humanity … is … in us, the defenders of the New Order.” Identifying with Nazism, Arrizubieta promoted anti-Francoist sentiments among Spanish workers, declaring that “if Germany wins the war, it should not respect the Spanish frontier.”

Faupel, still bitter at Franco for asking Hitler to replace him as ambassador to Spain in 1937, fought to assert control over the dwindling Spanish community of 1944-45. Together with his wife, Edith, the old general won over the most ardent Falangists left in Berlin. The Faupels hoped to use these collaborators someday to overthrow the Franco regime. Despite the protests of the Spanish embassy, the German government refused to silence Faupel and Enlace.

The Red Army launched its final offensive against Berlin on 16 April, sending into battle hundreds of thousands of men, tens of thousands of tanks and artillery pieces, and an air force that owned the German skies. The city was a fortress, surrounded by five rings of fortifications guaranteed to make the Soviet assault a costly one. Rejecting the pleas of his military and political advisers to fly out of the Berlin pocket, Hitler decided to remain and personally lead the defense of the city, entrusting Joseph Goebbels to embolden the last defenders of Nazism. The Battle of Berlin was an international struggle, pitting Stalin’s multiethnic Soviet Army against the outnumbered and outgunned remnants of Hitler’s New Order. While the vast majority of Berlin’s defenders were Germans in the regular army of the Wehrmacht, Frenchmen, Norwegians, Danes, Italians, Dutch, Romanians, Belgians, Hungarians, and other nationalities, mostly in the Waffen-SS, also defended the dying capital of the Third Reich. In the “apocalyptic atmosphere” of this brutal battle, Spanish accents could be heard from the small band of Iberians remaining in Germany.

Those non-Germans who kept fighting had abandoned their homes and families to fight for the disappearing dream of the New Order. By 1945, this continental vision was confined to a shrunken remnant of Central Europe, stretching from the Alps to the Norwegian Arctic Circle. In the final months only the most deluded could still have expected victory, the rest hoping for a last minute collapse of the Allied coalition. Fantasy was all that remained, with the surviving Spanish soldiers perhaps dreaming of a last desperate battle, where by force of will Germany and its remaining supporters would expel the invaders from the home of the New Order. What else could they do? They had made their choice: 1945 was not a time for second thoughts. For the most part, however, desperation had replaced hope. Surrender meant imprisonment or death at the hands of the Allies. Desertion was still a crime against Germany, punishable by death. In uniform, these exiles could at least hope to die among comrades.

From January to April, the Einheit Ezquerra fought on what remained of the Eastern Front, suffering tremendous casualties without much result. After additional recruiting and transfers from other units, by mid-April Ezquerra cobbled together just over 100 Spaniards for the final defense of Berlin. This recruitment was stymied by the actions of journalist and press attache Rodriguez del Castillo, who used his contacts in the DAF, Nazi party, and Armaments Ministry to secure exit permission, work releases, and safe-conduct passes for several hundred Spanish workers.

Most Spaniards serving in various units of the SS and German armed forces remained at their posts, however. Some, like Miguel Ezquerra, who became a schoolteacher after the war, survived; many did not. Like the millions of Germans and others who laid down their lives to preserve the Third Reich, they did so in the hopes of building a better Europe than the one they had inherited. Whether Falangists or convinced Nazis, the Spaniards of the Ghost Battalion defied their own government to fight for a destructive regime even as it collapsed around them in 1944-45.

Franco, who had boldly declared in 1942 that one million Spaniards would defend Berlin if need be, retreated under Allied pressure from these declarations as soon as the course of the war changed. The hundreds of Spaniards who wore the uniform of the Waffen-SS and Wehrmacht after D-Day made no such retreat. Franco survived the war with his power base intact: they and their ideology did not.

The presence of the Spanish volunteers in the final phase of the Third Reich represented a failure for Spanish foreign policy, which was characterized after 1943 by an effort to end collaboration with Nazi Germany. Ironically, the greatest impact of the Ghost Battalion was to undermine the New Order in Spain. After the war, the Franco regime was branded a collaborationist state, and its subsequent exclusion from the United Nations, the Marshall Plan, and the Western alliance structure until 1953 largely resulted from its wartime support to the Nazis, support which it found itself unable to end as cleanly or as quickly as Franco would have preferred.