In the wake of the Battle of Nagashino, Oda Nobunaga went on to conquer much of central Japan before he was ambushed by a traitorous subordinate, Akechi Mitsuhide, in 1582. Mitsuhide’s men surrounded the temple at Honno-ji and fought their way into the courtyard, where one of them shot Nobunaga in the side with an arrow. Supposedly he pulled out the arrow, then took up his own bow and killed many of the attackers. He finally received a musket ball in his arm, which ended his resistance. It is said he turned and walked into a burning temple to end his own life.

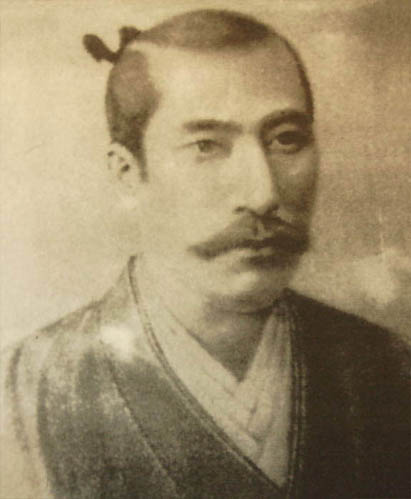

Modern judgments of Oda Nobunaga’s character are not kind. Unlike many of the generals discussed thus far, he had few redeeming characteristics. One thinks of modern views of Alexander, best summed up in the title of one of his recent biographies, “killer of men.” But as George Sansom notes in his history of Japan, Oda’s methods “were utterly ruthless in a ruthless age.” A successful general, he was not an inspirational leader, though he received the loyalty of two talented men, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, who would lead his armies and succeed him as unifiers of Japan.

Perhaps his primary military importance in Japan was his ability to innovate. He was among the first to recognize the potential of match-locks, learning how to shoot and acquiring as many manufacturing centers as possible. Here he also encouraged the production of cannon. These had been used, as had the teppo, by pirates, but Nobunaga was the first to use them on a large scale on land, for both offense and defense. It is the arquebus, however, that is most important. Most accounts of the Battle of Nagashino credit Nobunaga with ordering firing according to rank, one group firing while the others reloaded. If indeed he fought in this manner, he was decades ahead of armies in Europe. It was Gustavus Adolphus who introduced massed matchlock fire into European warfare during the Thirty Years War a half-century after Nagashino. Oda Nobunaga promoted the manufacture of gunpowder as well, in order to be less dependent on foreign supply. He promoted the use of ashigaru as regular troops rather than militia, and by making them full-time soldiers gave them discipline and status that heretofore had only been in the hands of the samurai. He also began his own navy and experimented with the concept of ironclad ships.

In the principles of war employed in this work, Nobunaga’s strengths were objective, the offensive, security, and exploitation. From the beginning of his career, Oda Nobunaga set as his political objective the leadership of Japan: “Rule the Empire by Force.” Strategically, he used his central location as a power base to which he would gradually gain land and men until he attracted the attention of the shogun and gained the necessary legitimacy to wage war on other enemies. In battle, the center of gravity for him was always the enemy army, whether in the open as at Okehazama and Nagashino, or in forts as at Mt. Hiei, Osaka, or Nagashima. Nobunaga benefited from the practice of the age of having daimyo lead their own armies, so “cutting off the head of the snake” was always a goal since surrender was not an option for such leaders. Subordinate commanders could become vassals, and he built his army in such a fashion, but rival daimyo (or religious leaders) ultimately would not survive defeat.

With the exception of taking up the tactical defensive at Shitaragahara, Oda favored the offensive. Although facing an invasion in his opening campaign, he refused to follow the advice of his older subordinates to defend his home castle. Instead, he took the initiative with a smaller force to ambush the Imagawa army at Okehazama. The speed of his reaction to the invasion, the analysis of the Imagawa position, and the fortuitous hailstorm amazed friend and foe alike. It was not, however, a tactic Nobunaga used often. He usually would not attack without a superior force and consistently did so after careful planning.

Although the battle at Nagashino is famous for Nobunaga’s use of firearms for defense, he introduced the widespread use of both hand-held matchlocks and cannon primarily on the offensive. He defeated the warrior monks in their castles with gunpowder weapons, including seaborne cannon aboard the ships of mercenaries hired for the assaults on Nagashima. Nobunaga’s early victories at Okehazama and Anegawa seem to have had no firearms employed, but the bulk of his campaigns after 1570 have them as an integral part of his army. His campaigns after Okehazama were strategic offensives, and he used this characteristic to his advantage tactically by choosing his battlegrounds when having meeting engagements. This is most apparent at Nagashino.

Nobunaga’s attention to the principle of security is best seen in two well-recorded instances. When alerted to the Imagawa invasion of his province, he met with his advisors in Kiyosu Castle. As mentioned earlier, his conversations that night consisted of social gossip. Even though this was his first battle and he was but twenty-six years old, Nobunaga knew enough to keep his plans to himself. If any of his less-than-enthusiastic subordinates decided to transfer his loyalty to the stronger invader, he could have taken Imagawa some men but no information.

At Nagashino, Oda was again holding a council on the night before the battle. One of his younger officers, Sakai Tadatsugu, suggested a sneak attack on the small force besieging the castle. He spoke out of turn and was quickly reprimanded. Turnbull comments, “However, Nobunaga interviewed him in private later, and assured him that he supported the plan. His anger had merely been a camouflage to throw any spies off the scent.” Kure also comments on security precautions within the Oda forces that night, asserting that one of the reasons for Katsuyori launching the foolish attack was because Takeda’s ninja scouts had all been killed by the Oda-Tokugawa troops before they could report the layout of the defensive position.

Surely the principle of exploitation is the one at which Oda Nobunaga excelled. As noted above, the center of gravity was always the enemy army. Nowhere was this more true than in his battles against the warrior monks. In his battles against rival daimyo, his forces killed large numbers of defeated troops in pursuit, but with the monks it became a matter of massacres. Whether he held a grudge against the Buddhists for their broken promises to keep his father alive or he crushed them with a view to keeping the newly arrived European Christians happy so he could maintain a steady supply of gunpowder, he was intent on wiping them out. In his initial victory at Mt. Hiei, he left few survivors. Turnbull says, “Mount Hiei was virtually undefended except by its warrior monks. The attack had the prospect of being a pushover, but the ruthlessness with which it was pursued sent shock waves through Japan. … The next day Nobunaga sent his gunners out on a hunt for any who had escaped, and the final casualty list probably topped 20,000.” At Nagashima in 1574, Oda had another 20,000 monks and local inhabitants surrounded in a temple and fort compound. He refused to negotiate with them as they starved, and finally set fire to the complex and burned them all.

Following his victory at Nagashino, Nobunaga invaded the province of Echizen, north of Lake Biwa, the home of a large population of Ikkoikki. As in the assault on Mt. Hiei, Nobunaga ordered a sweep through the province, killing anyone his soldiers encountered. They killed untold thousands; while his troops took countless men and women with them as slaves to their respective home provinces, they took no monks prisoner. Only at his victory at Osaka Castle, the headquarters of the warrior monks, did Nobunaga show mercy. A long siege finally ended with an appeal for clemency by the emperor. Oda had arranged for the imperial letter to be sent in order to bring the battle to an end, but he honored the surrender agreement. He burned the buildings, but killed no more monks.

It is as an innovator that Oda Nobunaga stands out in Japanese military history. Like other commanders discussed in this work, he saw the technological wave of the future, and he rode that wave to both military and political victory. By creating larger standing armies of peasant warriors to supplement the traditional samurai, and by using that increased manpower to implement massed firepower, he was key to the decline of cavalry in Japan. A similar decline had been taking place in Europe for a century thanks to archers, pikes, and guns, but it came about much more rapidly in Japan because of the tactics Nobunaga implemented. Though remembered as ruthless and dispassionate, Nobunaga remains a critical figure in the formation of the Japanese military and the ultimate unification of Japan.