From January to September 1918 Paris fell victim to a number of air raids conducted by German heavy bombers, popularly known as the ‘Gotha’ raids after the type most frequently used. These were just the latest in a series of attacks first launched at 12.45 pm on 30 August 1914, when a Taube overflew the city at a height of 1,000 metres and dropped five bombs, killing one civilian and wounding four others before flying off untouched by the guns of the city’s garrison, the Camp Retranché de Paris. Four armed Farmans operating as HF28 were immediately allocated to the CRP, but to little effect, and the raids continued over the next three months, killing eleven and wounding fifty. On 2 September one Farman did manage to get within range, but its machine gun jammed on the tenth round and the intruder got away unscathed.

Paris was also under threat from enemy Zeppelins, whose exceptional range required the capital’s air defences to be reinforced in all directions. ‘[Artillery and searchlights should be] located at key points outside the capital and linked by telephone, via the armies, to various posts distributed along the front,’ Joffre advised the minister of war. ‘This should give sufficient warning of the bearing of enemy dirigibles for our batteries to take the necessary action.’ General Gallieni favoured mobile motorized AA units but the lack of available chassis made his plan unviable. Instead, an outer ring of listening posts was set up about 100 kilometres from the city, with an inner ring of fifteen fixed batteries – each deploying two 75mm field guns, four machine guns and some searchlights – placed on the most likely access routes. As soon as the alert was sounded, a complete blackout would be imposed across the city. A second line of listening posts was soon added in a semicircle some 20 kilometres north and east of the centre, but all these dispositions remained untested until 21 March 1915, when two Zeppelins bombed the city with relatively little damage. The early warning system worked well enough, the artillery less so – the guns struggled to find the right range and tended to fire indiscriminately. An extra seventeen planes were added to the strength but during a raid on 28 May 1915 not a single CRP machine made it into the air. Standing patrols were then introduced, again with little impact. Details of the enemy bearing could only be conveyed via cloth panels laid on the ground, messages could take up to an hour to travel from listening post to airfield, and the latest and most powerful aircraft types always went to the front. In consequence, the planes seldom had time to reach interception height.

On 21 October 1915 Paris was cloaked by a thick blanket of fog: ‘We’ll cop it if we have to go up in that,’ remarked Adjudant Marcel Duret (CRP) to his observer Tavardon. But a Zeppelin was reported approaching the city and Duret received orders to mount a standing patrol. His comrade Sergeant Paul soon crashed, disoriented by the mist. However, Duret struggled on: ‘I was lost as soon as I left the ground,’ he later claimed. ‘I wanted to turn back after a near miss with a Voisin, then the drama began. I climbed to 2,200 metres, circling so I didn’t stray too far from the airfield. The pale moon cast an eerie light on my machine. It felt like the last dawn of the condemned man. I was starting to worry. “We’ve had it, old man,” I said, leaning towards Tavardon. “There’s nothing else I can do. I’ll try to hang on until we run out of juice.”’

Duret had plenty of fuel in the tank, time enough to find a landmark if he could. The lake at Enghien-les-Bains, just north of Paris, was the first obvious target. Then he spotted more lights. Convinced it was the centre of the city, he descended into a fog bank and promptly lost all vision: ‘My final recollection is of pulling back hard on the joystick. The next thing I was pinned beneath a pile of splintered wood. I called out twice without reply so I was pretty sure Tavardon was dead. I couldn’t breathe. I was choking. I couldn’t move. I thought, “If we’ve come down in the back of beyond, that’s it. I’ll suffocate before help gets to me.” Fortunately, a brave woman and two or three others came to my rescue just moments later.’

German planes penetrated the defences twice more, on 29 and 30 January 1916, when heavy fog again stopped the guns and searchlights from engaging the enemy. Twenty-six aircraft braved the weather on the first night, five spotting the intruder but none able to match it for height or speed. The following night a dozen planes went up, but the fog was thicker still, forcing them back to the airfield. ‘No use complaining!’ proclaimed La France illustrée. ‘It’s war. War, German style! Our enemies have handed us another lesson. We may equal them in will to win, but do we match them in our determination to develop weapons of war, acquire the technical superiority required to counter the threat of their evil genius, find new applications for science, or make new discoveries, however small?’

On 24 April 1916, a dark and cloudy night, several Farman MF.11 took off in search of a Zeppelin (probably LZ.97) returning from a raid on London. Their pilots included Captain Maurice Mandinaud (MF36/N81): ‘[Suddenly I spotted] a point, a long way off and very high in the sky. A point not of light but of darkness, more solid than the surrounding blackness. A cloud? No, it was moving too quickly. I thought at first it was a fellow pilot heading for home. I kept my eye on it. It seemed to be coming towards us, heading for the Belgian coast. Then another point appeared to its right. No sooner had I decided they were two of ours than I realized the first was a Zeppelin. It was very small, not much bigger than my finger end, so it was still a long way off. And it seemed very high. I circled to gain height, keeping my eyes trained upon it. It was still heading towards us and now we were both at the same altitude. At 2,000 metres it was clearly still oblivious to our presence. By the time it spotted us, we were at 300 metres, almost upon it, and my observer Lieutenant [Pierre] Deramond was preparing for combat. Then, to our astonishment, the gigantic airship reared up at an angle of at least 30 degrees and began to climb at … frightening speed, far beyond anything we could match…. Fortunately the Zeppelin stopped moving forwards while it climbed … so we could circle again to reach its new height.

‘By now the enemy was on the alert [and] we joined combat. We were close enough to obtain an excellent view down on to the envelope. Machine guns were mounted on platforms aft, right and left, and they opened fire. Our 130hp Farman only had seventeen bombs and a machine gun with a few tracer bullets, [but] we made seventeen passes around 100 metres above the enemy, returning fire each time. We were pretty certain we’d hit the target every time but we could see no outward signs of damage. With every pass came the same awful surprise…. It was no holds barred. We fired all our rounds from point-blank range without ever seeming to deliver the knock-out blow. But … the seventeen bomb holes must have compromised the airship’s buoyancy and produced a serious loss of gas. In an abrupt, daring and undoubtedly perilous manoeuvre, the huge mass began to dive towards the ground, zigzagging at speed before eventually crashing on to the Belgian plain. The ground was still swathed in darkness, but we were able to watch the Zeppelin fall by the first light of dawn. I wanted to spend longer observing its death throes, but the dense fire of the AA batteries and the state of our plane forced us to put safety first.’

Mandinaud had to put down in the neutral Netherlands, where he and Deramond were interned for a time before later escaping back to France. The Zeppelin survived the crash.

Night flying required particular skills, researched over the summer of 1917 by Captain Henri Langevin, CO of N313, from his base in the Dunkerque suburb of Coudekerque. He correctly identified the operational height of the German bombers (about 3,000 metres), so improving the accuracy of French anti-aircraft fire. He also demonstrated the effect of moonlit nights on visibility: aircraft silhouetted against the moon’s reflection in the water could be spotted over the sea but disappeared from view as soon as they crossed the coast. Impressed by his work, GQG transferred N313 to Avord to work up as a dedicated night-fighter squadron, an ill-timed move that removed it from the line just as the Germans stepped up their bombing campaign against Dunkerque. The French eventually set up a dedicated night-fighter school at Pars-lès-Romilly in September 1918, but only a handful of men had completed the course before the armistice.

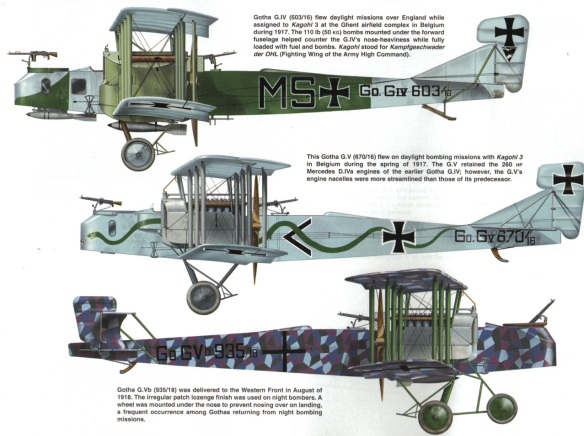

The German Gothas first appeared over the front in the late summer of 1916 and began raiding London the following year. Maxime Lenoir (C18/N23) was patrolling the front lines when he encountered his eleventh and final victim on 25 September 1916: ‘No ordinary opponent … but a three-seater [Gotha] equipped with two machine guns, each with its own crewman … How did I ever manage to defeat this flying house? How was I not blinded by the explosive bullet that brushed my eye …? How did I struggle home despite all the damage inflicted on my Nieuport Bébé? How did I, a mere David, eventually come to see Goliath strewn in pieces across the sky? I don’t know. But I do know the delight I experienced on witnessing the eventual outcome of this encounter. My victim crashed close to Fromezey, the wreckage burying the mangled bodies of the three Boches who’d tried to shoot me down – and very nearly succeeded. My engine had holes in two of its cylinders. The bullets had passed clean through the tank, thankfully without igniting the fuel inside, severing a strut and two cables. What’s more – and this shows how close we came in combat – my plane was drenched with German blood. It was streaming down the wings and the engine cowling.’

Georges Guynemer (MS/N/SPA3) also found the Gotha a tough nut to crack: ‘On 8 February [1917] I set off on patrol with my comrade [André] Chainat. Of course, the Boches still thought themselves untouchable and were planning a brazen attack on Nancy, but we were keeping our eyes peeled. Suddenly we spotted a huge plane with two Mercedes 200hp engines and a three-man crew firing in all directions. It was a Gotha, a truly formidable aircraft, but relatively unknown [at the time]. Without hesitation, we both attacked full tilt from opposite directions. I wasn’t worried about Chainat. He was very easy to work with – brave, skilful and cool. The [Gotha] offered a number of blind spots for a counter-attack and we quickly sought them out. It really would have been harder to miss [them]. We fired off entire strips and managed to silence the enemy guns. We forced the aérobus down behind our lines at Bouconville with a hole in its radiator. All three members of the crew were taken prisoner. Their plane had taken 180 rounds.’

Between January and September 1918 the Germans flew 483 separate sorties over Paris. The capital’s air defences had been strengthened with extra weapons, sound locators and searchlights since 1914, and decoy cities were also planned for Conflans and Villepinte to try to fool the raiders. So intense was the defensive barrage that less than a tenth of the enemy raids reached the city centre; eleven victories were claimed and many planes elected to drop their bombs on the heavily industrialized northern suburbs instead. The French hailed this as a moral victory, but the many factories in the area suffered significant damage, as did the important railway junction at Creil.

‘Everywhere – if one looks for them – large white cards are hung on doorways,’ wrote American Mildred Aldrich, visiting friends from her home near Meaux. ‘On them are printed in large black letters the words “ABRIS 60 personnes,” or whatever number the cellars will accommodate, and several of the underground stations bear the same sort of sign. These are refuges designated by the police, into which the people near them are expected to descend at the first sound of the sirènes announcing the approach of the enemy’s air fleet. More striking than these signs are the rapid efforts being made to protect some of the more important of the city’s monuments. They are being boarded in, and concealed behind bags of sand…. Sandbags are dumped everywhere, and workmen are feverishly hurrying to cover in the treasures, and avoid making them look too hideous. They would not be French if they did not try, here and there, to preserve a fine line.’ One night the alarm sounded: ‘My hostess and I tumbled out of our beds, unlatched the windows so that no shock of air expansion might break them, switched off all the lights and went on the balcony just in time to see the firemen on their auto as they passed the end of the street, sounding the “garde à vous” on their sirènes – the most awful, hair-raising wail I have ever heard – like a host of lost souls. Ulysses need not have been tied to the mast to prevent his following the song of this siren! We were hardly on the balcony when, in an instant, all the lights of the city went out, and a strange blackness settled down and hugged the housetops and the very sidewalk. At the same instant the guns of the outer barrage began to fire, and, as the night was cold, we went inside to listen, and to talk. I wonder if I can tell you – who are never likely to have such an experience – how it feels to sit inside four walls, in absolute darkness, listening to the booming of the defence, and the falling of bombs on an otherwise silent city, wakened out of its sleep. It is a sensation to which I doubt if any of us get really accustomed – this sitting quietly while the cannon boom, and now and then an avion whirs overhead, or a venturesome auto toots its horn as it dashes to a shelter, or the occasional voice of a gendarme yells angrily at some unextinguished light, or a hurried footstep on the pavement tells of a passer in the deserted street, braving all risks to reach home. I assure you that the hands on the clock-face simply crawl. An hour is very long. This raid of the 17th lasted only three-quarters of an hour. It was barely half-past eleven when the berloque sounded from the hurrying firemen’s auto – the B-flat bugle singing the “all clear” – and, in an instant, the city was alive again – noisily alive. Even before the berloque was really audible in the room where we sat, I heard the people hurrying back from the abris – doors opened and banged, windows and shutters were flung wide, and the rush of air in the gas pipes told that the city lights were on again.’

On 23 March 1918 the Germans also opened up with the ‘Paris Gun’, the so-called ‘Big Bertha’ – actually two weapons, both 210mm railway-mounted cannon, based near Crépy-en-Laonnois, 121 kilometres from the capital. The first shell landed at 7.15 am in the Place de la République; the second, fifteen minutes later in the Rue Charles V; and the third, in the Boulevard de Strasbourg. Over the next twenty-four hours a total of twenty-one shells landed in the city itself, and one in Châtillon. Only by reassembling the fragments did the French work out that they were dealing with artillery and not aircraft. René Fonck (C47/SPA103) was at the front that day. ‘We received a telephone message during the afternoon telling us they were shelling Paris,’ he recalled. ‘The news seemed so improbable that everyone burst out laughing. I preferred to keep my own counsel. How could a gun sited more than 120 kilometres away drop a shell close to the Gare de l’Est? Everyone thought the idea quite frankly ridiculous. But then, how could aircraft possibly conduct a daylight raid, pass unseen through a swarm of SPADs all positioned to stop them, and drop bombs all morning? The gun hypothesis offered the only possible explanation. Simply the range remained unexplained.’

Sound location gave the French the approximate position of the guns, quickly confirmed by the aircraft of SPA62. ‘Then we were over the Boches,’ recalled Lieutenant Jean de Brettes. ‘Nobody had fired at us yet. Not a good sign, it must mean that enemy patrols were around. North-east of the Saint-Gobain forest, the Germans suddenly opened up with anti-aircraft fire. The shells were all bursting at my exact height and I had to dodge to avoid them. My observer began taking photographs. Now we were over Crépy, the batteries still going hammer and tongs. The SPADs never left me for an instant. At one point they dived across me towards six German fighters. The [Boches] shot down one of our chaps, then headed towards Marie. Someone came spinning down. A Boche or a Frenchman? I got my answer five minutes later [when] just three SPADs followed me across our lines. I hoped our comrade had only been wounded. The mission was over: I was first to land and as each aircraft followed we all ran over in search of news. Once we were all down, we found out the missing pilot was Lieutenant Lecoq. We later discovered he’d been the one shot down over our lines by the six Boches. He’d taken a number of hits to the body. Although our photos weren’t great, they did show the exact location of the “Berthas”, so we could start correcting the fire of the guns detailed to destroy the enemy “colossi”. During the flight my colleague Adjudant [Charles] Quette spotted a flash that proved to be one of the Crépy guns firing. A few days later new photographs were deemed necessary to complete the information gathered during our first trip and to confirm the effects of our fire. I was picked again, with Lieutenant [Paul] Brousse as my observer. A second crew accompanied us: Adjudant Fabien Lambert (pilot) and Lieutenant [Robert] des Allées (observer). Despite adverse weather conditions, sustained and accurate anti-aircraft fire, and the continual presence of enemy fighters, we got [our] new photographs.’

French counter-battery work began immediately, but to little avail. The site lay hidden deep within woodland and was protected by a smokescreen as well as anti-aircraft guns. According to the authorities, 367 shells landed on Paris between 23 March and 9 August 1918, the most lethal attack taking place on 29 March, when the ancient church of Saint-Gervais-et-Saint-Protais in the fourth arrondissement took a direct hit during the Good Friday service: 91 worshippers died and 68 more were wounded. French artillery and bombers were all unable to halt the shelling, and only the allied advance during the second battle of the Marne in July prompted the Germans to withdraw the massive guns out of range.

‘Berthas by day, Gothas by night,’ proclaimed l’Illustration, ‘the dull rumble of the guns at the front, the uhlans just “five marches” from the boulevards … things should be pretty grim in Paris just now! [Yet] everyday life continues, no airs, no graces and no faint hearts. This is our Paris in wartime: no fuss, no panic, no bravado. A model of steadiness and self-control.’ Writing for the magazine Everyweek, Marie Harrison described the bombardment as a period of ‘acute unpleasantness’ because the shells arrived unpredictably, unlike an air raid which at least had a definite beginning and end. ‘Yet,’ she gushed, ‘I found Paris brighter than London, I found it more alive, more interested and so more interesting.’

Mildred Aldrich also detected few signs of panic: ‘Every one hates it. But every one knows that the chances are about one in some thousands – and takes the chance. I know of late sitters-up, who cannot change their habits, and who keep right on playing bridge during a raid. How good a game it is, I don’t know. Well, one kind of bravado is as good as another. Among many people the chief sensation is one of boredom – it is a nuisance to be wakened out of one’s first sleep; it is a worse nuisance to have proper saut de lit clothes ready; and it is the worst nuisance of all to go down into a damp cellar and possibly have to listen to talk.’

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, a Swiss national and trainee architect better known as Le Corbusier, was an unrepentant night owl. In February, when bombs fell close to his home and office, he stayed out on the Pont des Arts, ‘enthralled’ by the action overhead. He eventually decided discretion was the better part of valour. But, he boasted, he remained calm, unlike the females of his acquaintance: ‘The women are another set of bombs about to go off. They make such a fuss. [The raids] don’t worry me, although after the unusually lively events of the past few days I’ve decided to weave my way past the cellars each night. I’ll say it again. Danger doesn’t bother me … I’ll make a damn fine soldier.’