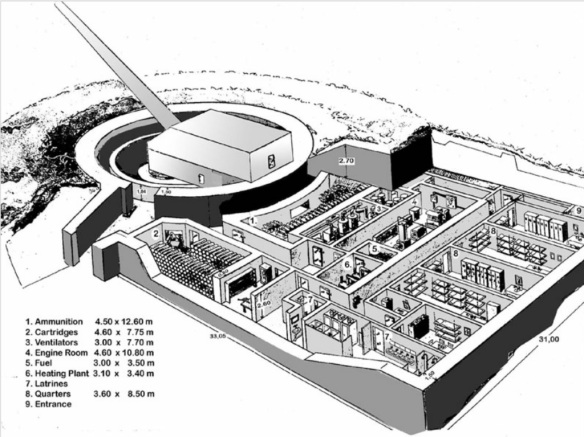

Cross-section of one of Mirus Battery’s gun emplacements. Modified drawing from Report on German Fortifications (Office of Chief of Engineers, US Army, 1944). The Germans captured four Russian 305mm Mle 1914 guns in Norway and installed them in Battery Mirus on Guernsey in the Channel Islands. These guns came from a Russian battleship salvaged in the 1920s. Eight of the guns had arrived in Finland before April 1940, but the ship carrying them was trapped in Norway.

Wn-70, Hamel-au Prêtre, a resistance nest above Omaha Beach between the Vierville and St Laurent exits. From Report on German Fortifications (Office of Chief of Engineers, US Army, 1944).

The Atlantic Wall was a porous barrier along the northern coast of France, extending to Belgium and Holland. Extremely strong in some areas, it was almost nonexistent in others because Germany lacked the troops to man the hundreds of miles required.

Nevertheless, beginning in 1940–41, the German armed forces and the Todt Organization of labor battalions began digging fortifications and pouring concrete. From the water inland, the wall consisted of obstacles, mines, barbed wire, automatic weapons, mortars, and artillery. Indirect-fire weapons such as mortars and artillery were far enough removed from the beaches to prevent any invaders from gaining a direct view of them without aerial reconnaissance.

From Japanese experience the Germans knew that once an American landing force was ashore, the island was lost. Similarly, no Anglo-American amphibious assault had yet been defeated in the Mediterranean. Therefore, without the option of defense in depth, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel determined that it was necessary to stop a landing on the beach, especially since he conceded air superiority to the enemy. The likeliest landing zones were well known, both in Normandy and the Pas de Calais area, and were defended accordingly. By June 1944 the wall extended eight hundred miles with some nine thousand fortified positions.

Beach Obstacles

Some of the most innovative defenses were the various obstacles deployed between the low and high tide marks. Spread from fifty to 130 yards below the high tide line, all were designed to destroy, disable, or impede Allied landing craft.

Farthest seaward, Belgian Gates (“Element C”) were welded steel structures in the form of grills, as their name implies. Variously six to ten feet in height and weighing upward of three tons, they were propped from behind by triangular frames and mounted on concrete rollers. Protruding above the top of the gate were three prongs that could be tipped with mines or left exposed to tear out the bottom of a landing craft.

Primarily intended to prevent assault craft from reaching shore, the gates also were placed astride main exits leading inland. Defenders could shoot through the gates at attackers, who could find almost no cover on the opposite side.

The next defensive line was a series of mined posts, slanting seaward with Teller mines attached to the top. They were set twelve to seventeen feet above low tide so that a landing craft striking the post at high tide would detonate the mine.

The third obstacles were tetrahedra—pyramid-shaped log frames with as many as three mines on the seaward leg, arrayed at different heights for better prospects of exploding on the bow or keel of a landing craft.

Finally, hedgehogs were both antiboat and antitank devices. Typically they consisted of three or four wide steel beams welded together, jutting upward from the sand. They could impale a landing craft or amphibious tank and, deployed farther inland, hedgehogs formed obstacles that no vehicle could cross. Rather than a solid line, they were often placed in apparently random fashion, when in fact the routes around them had been sighted in by mortars or antitank guns.

Concrete Bunkers

Most of the concrete structures along the Normandy coast were built to standard specifications. They included massive casemates housing heavy-caliber guns and smaller emplacements generically called “Tobruks” after similar defenses in North Africa. Nearly all were reinforced with steel bars, and some were thick enough to withstand direct hits from Allied bombers or warships.

The bunkers, also mostly built to standard specifications, housed a wide variety of coastal defense artillery ranging from 100 to 210 mm (See Artillery, German). Of the thirty sites in Normandy, fourteen contained 105 mm guns and ten contained 155 mm weapons.

Knowing that any such structures would draw Allied attention, the Germans constructed dummy bunkers. They lacked artillery pieces, but some were defended by riflemen and machine gunners to convince the invaders of their validity as targets.

Additionally, hundreds of prepared fighting positions were dug, linked by communications trenches, some of which were underground. Many were camouflaged to seaward as well as overhead, making the exact location and nature of the defense difficult to ascertain from any distance. Such positions were termed Wiederstandneste, or resistance nests. Each was assigned a number for easy reference in case one required reinforcement.

Inshore Defenses

The German army had vast experience with automatic weapons dating from the First World War, and it laid out carefully calculated fields of fire from bunkers and open positions. The excellent MG-34 and MG-42 machine guns were placed to provide overlapping coverage of most landing beaches, a technique well demonstrated in Saving Private Ryan.

On some beaches antitank ditches were dug, usually inland of a natural rise or seawall. The ditches were wide enough to prevent Allied tanks from crossing without dropping into them, and the opposite grade was too steep to scale easily. The ditches were preregistered by artillery, mortars, and antitank guns sited for good fields of fire.

Well inland, many open fields had been spiked with tall poles (“Rommel’s asparagus”) to deter Allied gliders. The poles were tall enough to shear off their wings, thus preventing a controlled landing. In some instances the poles worked effectively.