Admiral Byng.

March 1757

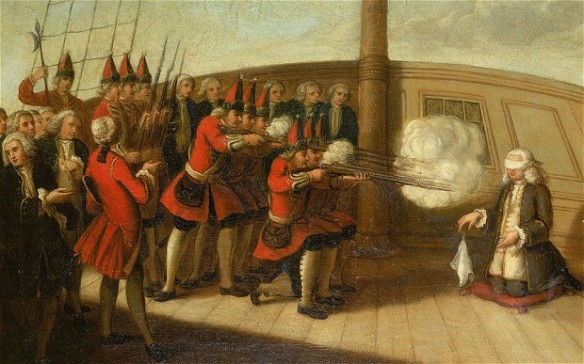

‘At twelve the Admiral was shot upon the quarter-deck,’ recorded the log of HMS Monarch moored in Portsmouth Harbour.

On 14 March 1757, John Byng, an Admiral of the Blue, died with courage and composure before a Marine firing squad. The trial and execution of Admiral Byng was one of the more disgraceful miscarriages of justice in the annals of the Royal Navy even by the standards of the time. Byng was the luckless scapegoat for the inadequacy of the navy and its commanders, a vacillating and neurotic British government and a mob, whipped to a frenzy by political pamphleteers.

By 1756, the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48) was still very much in the public consciousness and had planted the seeds for what was now to become the Seven Years War. The civilised world was in a state of anxiety and tension verging on paranoia. The War of the Austrian Succession began when Maria Theresa succeeded her father, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, to the vast Hapsburg possessions in Europe, and the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in October 1748 drew matters to an uneasy close.

The simmering enmity between Prussia and Austria had never really dissipated and the alliances forged after the War of the Austrian Succession were, again, thrown into disarray in 1756. In January, Britain and Prussia formed an alliance against the two old enemies, France and Austria. Conflict began in the autumn of that year with the invasion and defeat of Saxony at the hands of Frederick II of Prussia. Britain’s worries were compounded by colonial rivalries with France and Spain, which had begun in 1754 in America over control of the Ohio valley.

Governance and leadership in Britain at the time was fragile. Cabinet was rent by petty quarrels, jealousies and rivalries. In March 1754, the Duke of Newcastle had assumed the leadership of the Whig party as first minister. Although facing the difficulty of controlling his ministry from the House of Lords, he had had long experience in government and was reasonably adept at handling the difficult George II. He was not a bad organiser, and had a good deal of common sense and integrity, unusual for the times. However, although his drawbacks were relatively minor, they were very obvious. He was perpetually in a state of anxiety and overexcitement. He also had great difficulty in concealing a substantial lack of self-confidence that led to public ridicule and mockery. In the House of Commons, Pitt and Fox were men of real stature, drive and political ruthlessness. Lurking in the wings was the redoubtable Duke of Cumberland, intent on making mischief. Admiral Lord Anson, an experienced and practical sailor, was First Lord of the Admiralty.

In May 1755, a small fleet under Admiral Boscawen was dispatched into the Atlantic to prevent the French reinforcing their troops in Canada and America. With France and Britain still technically at peace, this was a high-risk strategy. Boscawen’s orders from the Admiralty were half-hearted and deliberately vague. In the event, he captured a mere two ships instead of the whole squadron that Newcastle had hoped for. The French, understandably, were indignant and rumours suggested that they were planning to invade England. There was a good deal of information being gathered but little of real substance. However, well-sourced intelligence was coming from the Mediterranean, particularly concerning the assembly of men and ships in Toulon. The objectives were obvious: Gibraltar and Minorca.

For controlling shipping movement in the Mediterranean from Gibraltar to the important ports in Italy, Greece and the Levant, Minorca was the ideal naval base. It had been a British possession since 1708. He who could hold Minorca for his fleet could control the exits from the ports of Toulon and Marseilles, and the Spanish from Barcelona, as well as reinforcing Gibraltar when necessary. The threat alone of a strong and efficient fleet based there would be enough in itself. Land forces on the island, without naval support, would not be as effective because they could be denied reinforcement and resupply, and eventually starved out or picked off at will.

Minorca had a perfect natural harbour adjacent to the capital of Mahon, on the eastern side of the island, for basing the fleet. This harbour was well protected by the strongly built Fort St Philip. By 1756, however, the defences had been neglected and there were doubts as to its strength against an assault by land. The garrison itself had been allowed to dwindle. The commander was the 82-year-old Lieutenant General Blakeney. In theory, there were four regiments (about 2,860 men) to defend the island but of these, an unbelievable forty-one officers were on leave in England, including all four of the regimental commanding officers, and the governor of the island and fort.

Administrative corruption, financial abuse and embezzlement in the British Navy at the time was serious. Speculators would buy up old and unseaworthy ships as war was approaching, knowing that they could let them out later, at exorbitant costs, to a desperate Admiralty. Shipbuilders used low-grade timber and nails that rotted and rusted soon after the ship put to sea. Rope was shortened and, when coiled up, looked the correct length but the moment it was first put to use, the sleight of hand by the suppliers became apparent. Work was charged for many times over with disabled, if not actually non-existent, people on the pay roll. Fraudulent dockyard bosses became rich on the proceeds. The fact is that there was very little confidence in the Royal Navy; its outstanding reputation was yet to be made and Anson, a brave and resourceful sailor, was not confident in the political scene and loathed the shenanigans of wily civil servants and ministers. His main job was to ensure that operations were carried out without too much loss, disaster and courts martial.

Into this unstable world stepped John Byng. Born in 1704, he was the fifth surviving son of George and Margaret Byng. George was one of the most respected admirals in the navy. He had gained early political and career progression by enlisting the navy’s support for William of Orange during the Glorious Revolution and thwarting the efforts of the Old Pretender in 1715 by cutting off Jacobite supplies from the Continent. In 1718, he was given the command of a large fleet in the Mediterranean to counter the Spanish and Austrian competition over their possessions in Italy. Off Cape Passaro, he decisively defeated the Spanish, preventing their attack on Sicily. Praise and honours were heaped upon him by a grateful government. He was made an Admiral of the Fleet in 1718, created Viscount Torrington and given the lucrative position of Treasurer of the Navy in 1721. On his accession, George II appointed him First Lord of the Admiralty.

Sons of illustrious fathers do not always live up to the hopes and expectations of their families but, in John’s case, he appeared to do so. As a 14-year-old midshipman, he was present at Cape Passaro when the Superb, in which he was serving, captured the flagship of the Spanish commander-in-chief. Although not involved in significant action until the final chapter off Minorca in 1756, he rose steadily through the ranks of the navy. His first command, as captain, was of the Gibraltar, a twenty-gun frigate, in 1727. Various commands followed, but despite the War of the Austrian Succession starting in 1740, Byng was not involved in action, rather in relatively humdrum appointments in Newfoundland and the Channel. However, in August 1745, at the age of 41 he was made a rear admiral. While this was not as rapid an advancement as some others, he was, nevertheless, probably lucky to have reached this rank so soon. He then commanded a small squadron in home waters, preventing the French from helping Bonnie Prince Charlie.

In 1747, he was made second in command to Admiral Medley in the Mediterranean with a large fleet, preventing the French from attacking the Austrians, now British allies, in Italy. In August of that year, Medley died. Byng was promoted to Vice Admiral of the Blue and assumed command of the Mediterranean fleet. No doubt apprehensive about the French threat of invasion of the homeland, the government withdrew about a third of the fleet, putting Byng in the unenviable position of being able only to blockade Toulon properly or spread his ships, generally, along the French southern coast. He chose the latter, but with the conclusion of the war in 1748 Byng was recalled home having never actually been in action. Though never having commanded a ship, let alone a squadron, in battle, he had made no mistakes and the government, confronted with the difficulties of many who had, were happy to promote someone whom they clearly thought would be a safe pair of hands, and, after all, they told themselves, he did have experience of the Mediterranean.

But what of Byng the man? Society of the time expected men of Byng’s background and standing to maintain a certain air of superiority and contempt for men who were perceived to be of lower status, particularly civilians. Society would not have been disappointed. Byng, a bachelor, now MP for Rochester with middle-aged widow Mrs Hickson as his mistress, knew his place. He ran a house in Berkeley Square and had built an imposing country seat, Wrotham Park, in Barnet. He was a well-built man and a contemporary portrait shows him in a flamboyant admiral’s coat, with large cuffs and protruding lace, to full advantage. He surveys his world with an air of pride and superiority. But does this cloud the insecurity of the son of a great man, particularly in the same profession? He was not known for his popularity and perhaps hid some of this lack of confidence behind strict and austere behaviour—he was known as a disciplinarian. He was fussy and precise over unimportant and trivial details. Decision-making did not come to him easily and although it is unfair to class this, in battle, as cowardice, it did not help when the need was to encourage subordinates who looked to him for guidance and leadership under stress.

In 1756, as the government realised the French threat of invasion was becoming more and more hollow, its concentration returned to the Mediterranean and the key strategic value of Minorca. Significant, and worrying, intelligence was being received in London from the various legations and consuls in the area that confirmed massing of French troops and shipping in Toulon. Commodore George Edgecumbe, a high-quality naval officer, was in command of the small Mediterranean squadron, consisting of some eight ships. His force was far too small to be able to carry out all the operations of blocking the French ports and projecting British power at sea. The French threat was all too obvious. They could destroy British trade and influence in the Mediterranean, combine with the powerful fleet in Brest and create a significant force in the Atlantic or send heavy reinforcements to the Americas. Nevertheless, the French did not have it all their own way; they experienced supply difficulties in making ships ready for sea at Toulon and the French court was as riven with jealousies and back-biting as the British Government over what direction to take. The two countries were still not at war. However, by February, with the appointment of the redoubtable Marquis de la Galissonnière to command twelve ships of the line and the arrival of the Duke of Richelieu in Toulon to command the army and stiffen resolve, the British could vacillate no longer and decided that Edgecumbe required reinforcing.

On 11 March 1756, Byng was promoted admiral and ordered to Portsmouth to fit out a squadron for service in the Mediterranean. He was not told how big it was to be or when it was to sail. This should not have been a problem. The Admiralty estimated that it required a fleet of forty battleships to defend England against invasion. At the time, there were some sixty-five in port or home waters, thus freeing twenty-five for a Mediterranean force. But there was still the nagging feeling that Britain was vulnerable to invasion, despite the increasing knowledge that it was virtually impossible. Of course, it suited the French to keep the pressure up. So Byng was allocated a mere ten ships of the line, with no frigates, store ships or hospital vessels—the Admiralty’s theory being that, once he joined up with Edgecumbe, they would be just superior in numbers to the French.

Byng arrived in Portsmouth on 20 March and quickly discovered all was not well. His squadron was present with the exception of one ship, but he was 700 men short. The Admiralty made it quite clear he was not to make up numbers from the other ships’ companies lying at Portsmouth and, moreover, he was to ensure one of the other ship’s companies, not in his squadron, was to be made up before any of his. To compound this, he was astonished to hear that three ships of the line and two frigates, with crews he desperately needed, were to be sent off on a frolic of their own to deal with some French convoy in the Channel. It cannot have done his blood pressure any good to be told that he was also to take two drafts of soldiers with him; one lot were the absentees from the Minorca garrison and the other a small reinforcement for Gibraltar. On top of that, he was to distribute his Marines to the other ships and, in lieu, take on Lord Robert Bertie’s 7th Regiment of Foot (now the Royal Fusiliers). The Fusiliers were not to replace the Marines (as close protection for the ships and boarding parties, etc.) but to be landed at Gibraltar. The governor of Gibraltar, Lieutenant General Fowke, was then to embark one of his Gibraltar battalions on board Byng’s ships for Minorca. Order, counter-order and disorder followed. Anson protested that the Fusiliers must remain on board to carry out the Marines’ tasks. The government then decided that Minorca would only need reinforcing with infantry if the French were actually invading, so the Fusiliers were to remain on board and Fowke was to add one of his battalions to the force only if Minorca was likely to be attacked. This shambles only added to Byng’s anxieties.

The next day he received a letter from the Admiralty that he was to set sail ‘with the utmost dispatch’ and would receive sailing orders on the 24th. This was the result of a panic message from the British minister in Turin that the French fleet were on the point of leaving Toulon to invade Minorca. In the meantime, Byng’s men were scouring the countryside for ‘recruits’ and the press gangs managed to collar the few who were either too drunk or disabled to escape. Nevertheless, Byng had made reasonable progress and, apart from lack of men, was ready to depart on receiving his orders to do so on 1 April. One can sympathise with Byng’s heavy heart as he replied, ‘With regard to the Instructions I have received, I shall use every endeavour and means in my power to frustrate the designs of the enemy, if they should make an attempt in the island of Minorca, knowing the great importance of that island to the Crown of Great Britain . . . and shall think myself the most fortunate if I am so happy to succeed in this undertaking.’

His shortage of men, even having scoured the hospitals, was still acute but over the next couple of days was largely made up with some pretty questionable individuals from other ships. The last ship of his squadron to join, the Intrepid, arrived but was in a state of disrepair, had not been warned for foreign service and was therefore short of provisions and ammunition. The remainder were better, but not much. All had been cleaned since December but two were leaky and others had been upgraded from old seventy-gun ships into more efficient sixty-fours, but were still not as good as the newly built sixty-fours. Others were below their gun rate. Out of a squadron of ten ships on a mission vital to the country, it was disgraceful that there should be so many deficiencies in ship capability, crew numbers and efficiency. None of this was the fault of the Admiral.