Frederick II, King in Prussia, ‘Frederick the Great’: picture by David Morier

1761

1761 turned out to be a year without a major battle on the main eastern front. There is a weary sense of déjà vu about the allied strategy. Marshal Daun, still recovering from the wound sustained at Torgau, anxious to resign and more static than ever, was in command in Saxony. His more enterprising subordinate, Laudon, was to join forces with a Russian army, now commanded by the tsarina’s favorite, Count Alexander Borisovich Buturlin, and seek to win a second Kunersdorf. Frederick left Prince Henry and 28,000 in Saxony to keep an eye on Daun, while he headed off to Silesia with the main army of about 55,000. His attempt to keep his two enemies apart failed, not least because he ducked an opportunity to attack the Russians at Liegnitz on 15 August. As things turned out, this was probably wise. Buturlin linked up with Laudon four days later but then proved very reluctant to go on the attack. On the day before their junction, Frederick told Prince Henry that “the Russians still have no desire to attack, but I think Laudon will force them to.”

The Austrian commander certainly tried but Frederick mounted a persuasive counterargument by taking his army into a fortified camp at Bunzelwitz to the northwest of Schweidnitz. Nature was given a helping hand by intensive spadework. Working in twelve-hour shifts around the clock, the Prussian soldiers created a formidable network of trenches and palisades. The Saxon Captain Tielke reported admiringly:

In this location the Prussian army stood on a series of low and mostly gentle eminences, which were utilized in a masterly fashion. The approaches were by no means physically insurmountable, but what rendered them difficult to reach were the little streams, the swampy meadows, and the enfilading and grazing fire from the batteries on every side.

Breaking into this fortress would have proved extremely costly, given the 460 pieces of artillery that guarded it. The Russians blinked first. First Buturlin told Laudon he would cooperate in a joint attack, then he had second thoughts. On 9 September he finally gave up and took his army back east to the river Oder and beyond.

At this point, this uneventful campaign should have come to an end with the two sides going into winter quarters. Frederick certainly thought it was all over. From Pilzen on 27 September he wrote to Prince Henry that it was next to impossible that the Austrians in Saxony would attempt another raid on Berlin, now that the Russians had gone, and as for those in Silesia “I believe you do not need to have any worries about us because essentially the campaign is over, given that neither we nor the Austrians intend to undertake anything.” He was wrong. There were three more incidents to come, one welcome, the other two decidedly not. The first was a brilliant piece of work by General Dubislav Friedrich von Platen and a corps of about 8,000, sent by Frederick to harry the retreating Russians and already underway. On 15 September they had attacked the main Russian supply base at Gostyn in Poland, destroying 5,000 wagons and taking 1,845 prisoners and seven artillery pieces. From there they moved on towards the Prussian fortress of Colberg (often spelled Kolberg) on the Pomeranian coast, disrupting the Russian supply lines as they went. But no sooner had Frederick sent off congratulations on this coup than the truly terrible news arrived that on 1 October Laudon had taken the great fortress of Schweidnitz with a sudden night attack. Frederick was completely nonplussed by this “so extraordinary and almost incredible turn of events.” It was indeed a devastating blow, for Schweidnitz covered the passes from Bohemia via Friedland and so was “the key to Lower Silesia,” especially since Glatz, which covered the routes from Königgrätz to Neisse, was already in Austrian hands. Given all he had suffered at Laudon’s hands in the past, most notably at Glatz and Hochkirch, Frederick’s complacency was as surprising as it was damaging. The third piece of bad news which arrived just before the end of the year was that Colberg had fallen to the Russians on 16 December, which gave them for the first time a port through which they could bring up supplies. For the first time, the Russians could winter in Pomerania and the Austrians in Silesia. Meanwhile in Saxony, Prince Henry had been forced out of his camp at Meissen by Daun.

The only chink of light was visible in the west, where the French had gone into winter quarters in the middle of November, having achieved nothing durable in the course of a long campaign. This was all the more disappointing for them because a major effort had been made that year. Two large armies were sent east, one totaling c. 95,000 from the Lower Rhine commanded by the Prince de Soubise and the other with some 65,000 from further south commanded by the Duc de Broglie. They thus outnumbered Prince Ferdinand’s forces by at least two to one. What then followed was a bewildering succession of marches and countermarches, maneuvers and countermaneuvers, the only real point of contact being the battle of Vellinghausen near Hamm on the river Lippe on 15–16 July, which was a clear victory for Prince Ferdinand. Although this did not end the campaign, it helped to ensure that there would be no conquest of Hanover in 1761.

1762

On 6 January 1762 a depressed Frederick wrote from Breslau to his chief minister, Finckenstein, that if the Turks could not be induced to open a second front against the Austrians in the Balkans, he was finished. So negotiations would have to be initiated in the hope of saving something from the wreckage for his successor, which was a hint that Frederick was contemplating suicide—again. Just two weeks later, on the 19th, he received news from his man in Warsaw that at long last the Tsarina Elizabeth had died, on the 5th. His immediate reaction was cautious. He wrote to Finckenstein that they could not be sure how her successor, Peter III, would act and whether he would succumb to the blandishments of Russia’s existing allies. The indolent British ambassador in St. Petersburg, Sir Robert Keith, should be stirred up to counter French and Austrian influence. He ended by adding gloomily that he did not suppose this change of ruler would do him any more good than had the accession of Charles III in Spain three years previously.

He could not have been more wrong. As the French complained, the new tsar had not so much an attachment as an “inexpressible passion” for Frederick, whom he hailed in a personal letter “one of the greatest heroes the world has ever seen.” He often wore the uniform of a Prussian major-general, displayed in his apartment all the portraits of his hero he could find and repeatedly kissed Frederick’s image on a ring sent from Potsdam as a present. This was partly hero worship and partly motivated by Peter’s need for Prussian assistance in regaining the duchy of Schleswig from Denmark for the House of Holstein from which he descended. It was not long before very good news was bringing cheer to Frederick. At a dinner at the Russian court on 5 February, Peter had expressed himself so intemperately about the shortcomings of his Austrian ally that the Austrian ambassador, Count Mercy, felt unable to repeat his actual words in his dispatch to Vienna. Orders were sent to the Russian generals to cease all hostile action against Prussia. The Turks and Tartars were encouraged to attack Austria. A treaty of alliance with Prussia was signed on 5 May. Peace between Prussia and Sweden was brokered by Russian diplomats and signed on 22 May. Frederick had to rub his eyes. Within just a few weeks, the north and east had been neutralized and Russia turned from enemy into ally. No wonder that he exulted when he came to write up his history of the episode:

The summary of events we have related will present to our view Prussia on the brink of ruin, at the end of the last campaign; past recovery in the judgment of all politicians, yet one woman dies, and the nation revives; nay is sustained by that power which had been the most eager to seek her destruction…What dependence may be placed on human affairs, if the veriest trifles can influence, can change, the fate of empires? Such are the sports of fortune, who, laughing at the vain prudence of mortals, of some excites the hopes, and of others pulls down the high-raised expectations.

Whether or not Frederick was saved by the death of the tsarina is so contentious an issue that it deserves separate treatment. Here it need only be remarked that Frederick was overdoing it. Had he known just how desperate was the situation of his enemies, he might have modified his view. When he heard that 20,000 men had been discharged from the Austrian army, he assumed it was because Maria Theresa was so confident of total victory. In fact it was because there was no money to pay for them. So many new taxes had been imposed and so many old ones increased, so many loans had been raised, that the Austrian well was bone-dry. Around 40 percent of annual revenue was now needed just to service the accumulated debt. By the time the war ended the following year, the debt had reached a total equivalent to seven to eight years’ regular income. The situation was no better in France, where a state bankruptcy began to look like a real possibility. When the Austrian financial expert Count Ludwig Zinzendorf was asked by the French ambassador about the fiscal structure of the Habsburg Monarchy, his response was: “Can one blind man show another the way?”

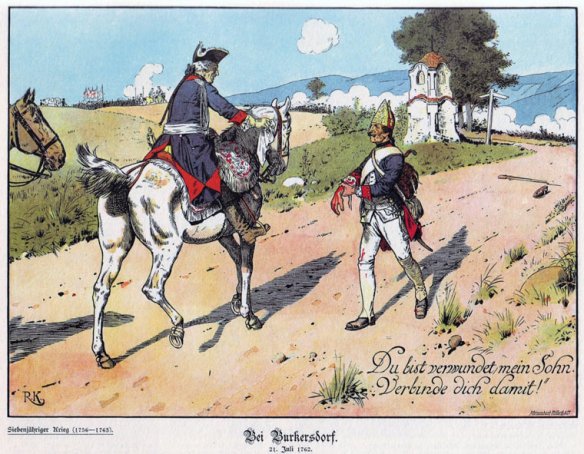

Once it became clear just how much had changed in St. Petersburg, Frederick turned positively jaunty. On 6 March 1762 he wrote to d’Argens that peace with Russia was certain, that this had caused great alarm in Vienna and that “the storm clouds are breaking up and we can look forward to a beautiful calm day, shining with rays bursting from the sun.” But there was still work to be done. Pomerania was being evacuated by the Russians. That left Silesia and Saxony to be regained. The chief target had to be Schweidnitz, for if the Austrians remained in control of Lower Silesia, they would have a strong hand to play at the peace negotiations. Leaving Prince Henry and 30,000 to keep an eye on Saxony, Frederick took an army variously estimated at between 66,000 and 72,000 to Silesia, where he found Daun and about 82,000 in defensive positions around Schweidnitz. There he was joined by 15,000 to 20,000 Russians under Chernyshev. Together, they pushed Daun back to Burkersdorf, southwest of Schweidnitz.

During the first two weeks of July, Frederick tried to induce Daun to move away by sending General Franz Karl Ludwig von Wied zu Neuwied (the younger son of a German prince) and a corps of 20,000 to cause mayhem in northeastern Bohemia. Daun appeared not to move, so most of this force was recalled. In fact, substantial numbers had been sent off to guard communications, with the result that when battle was joined at Burkersdorf, Frederick for once enjoyed numerical superiority. This would have been even greater if the Russians had been actively involved. On 18 July, however, Chernyshev had to tell Frederick that a palace revolution in St. Petersburg had deposed and killed Peter III and that he and his army had been recalled. With the aid of what amounted to a large bribe, Frederick persuaded him to stay put for three days, albeit in a noncombatant role. In fact, Chernyshev’s corps played a crucial role when the battle began on 21 July. Frederick placed it, together with eleven battalions of his own, opposite the Austrian army to fool Daun into thinking that it was there that the main attack would be launched (see map). Meanwhile, the main Prussian brigades were sent off to take up positions to the northeast and east, which were weakly guarded. It was their assault which threatened to turn Daun’s flank and forced him to order a general retreat. As battles of the war went, this was a relatively bloodless affair, with each side suffering around 1,600 casualties but the effects were of the greatest political and strategic importance. Burkersdorf would also turn out to be Frederick’s last battle. Daun was pushed back into the Bohemian mountains and was cut off from Schweidnitz. The siege lasted sixty-three days, as the Austrian garrison commanded by General Peter Guasco, an experienced engineer, defended the fortress with enterprise and resolution. Only after a lucky Prussian bomb blew up a magazine and opened the way for an assault did he surrender, on 9 October. This was a crucial moment, for in effect it returned Silesia to Prussian control. Commenting on Daun’s inactivity as the siege progressed, Jomini wrote: “Modern history offers no comparable example of cowardice.” In the west, the campaign ended with the capitulation of the French garrison at Kassel on 1 November.

By this time, Kaunitz’s great coalition was falling apart. It was clear that Great Britain and France would soon negotiate a peace (a preliminary treaty was signed on 3 November 1762) and also that the new ruler of Russia, Peter’s widow, Catherine, would not resume hostilities against Frederick, for the good reason that Russia was financially exhausted. Austria was soon going to be on her own. The last straw was the decisive victory achieved by Prince Henry on 29 October at Freiberg, southwest of Dresden, which in effect restored Prussian control of Saxony. An exultant Frederick wrote to tell him that the news had made him feel forty years younger: “Yesterday I was sixty, today I am eighteen again.” He told the Duchess of Saxony-Gotha that Fortune, having persecuted him for seven campaigns, now seemed to have decided to treat him more leniently, and that peace was within his grasp. He was right. At Vienna, even the hardest of hardliners could now see that he could not be defeated. Of all the combatants, it was Saxony which had suffered most and so it was appropriate that a Saxon, Karl Thomas von Fritsch, should have been chosen to inform Frederick that Austria was ready to negotiate. That happened on 25 November at Meissen.