The Allied and Central Powers entered World War I in various states of readiness and with a number of artillery doctrines. Confident in its much vaunted 75mm field gun, France based much of its faith in mobile, relatively light-caliber, rapid-fire tactical artillery. By 1914, Germany and Britain, as well as Russia, had also developed reasonably efficient quick-firers. In addition, Germany also saw heavy yet mobile guns and howitzers as the key to rapidly neutralizing Belgian and French fortifications in accordance with their Schliefen Plan. Other belligerents, such as the United States, were less prepared and were forced in many cases to improvise rapidly to meet the challenges of a world war. The United States thus fought the war with predominantly foreign-designed and -manufactured ordnance.

The war also saw the introduction of new, more lethally efficient projectiles. In their search for a compound stable enough to withstand the shock of firing yet explode violently on target, British scientists experimented with picric acid, a chemical used in the dyeing industry. Using picric acid, they ultimately developed lyddite, to create a practical high-explosive (HE) shell for British service. The other major powers quickly followed suit, and high-explosive shells became a standard component in the world’s arsenals. In 1914, Germany began using even more explosive TNT as a high-explosive bursting charge. Other new projectiles included smoke shells containing white phosphorus, to obscure troop deployments, and, as World War I progressed, shells containing poison gas.

In an effort to produce inexpensive cast iron projectiles capable of inflicting maximum casualties, Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for the Advancement of Science developed a xylyl bromide gas shell in 1914. Although the first German shells proved largely ineffective on the Eastern Front the following January, other, more lethal shell designs followed. The French replied with much improved, larger shells filled with just enough explosive to crack the shell casing and release their deadly phosgene gas. First used at Verdun, the French shells set the standard for future developments. Soon after Germany fielded an array of gas shells, including the so-called Blue Cross projectile containing arsenic-based smoke, phosgene-filled Green Cross, and the insidious Yellow Cross, containing mustard gas. As the war progressed, gas became an everyday threat to frontline troops of all sides.

Although both the French and German artillery saw limited success during the early stages of the war, the realities of trench warfare forced both sides to modify their initial doctrines. Because entrenched troops were protected from the flat trajectory of direct-fire guns such as the French 75, the war saw the ascendancy of the indirect fire of the howitzer, with its arcing trajectory and heavy shells. Other new weapons also arose during the war, including antiaircraft artillery and self-propelled and antitank weapons, as well as the super heavy long-range railroad gun.

Long-range indirect fire also necessitated advances in fire control. Although notoriously unreliable, field telephones gave forward observers unprecedented communication with artillery officers far to the rear. Artillery officers also learned to formulate timetables to coordinate preparatory barrages before infantry assaults to avoid casualties from “friendly fire” and yet disrupt the enemy’s defensive capabilities.

During the September 1917 siege of the Russian-held Baltic city Riga, General Oskar von Hutier, commander of the German 8th Army, demonstrated a degree of originality rarely matched by Allied commanders. Aided by his artillery commander, a Colonel Bruchmuller, he proved the effectiveness of coordinating the infiltration of the enemy’s lines by specially trained storm troops combined with flexible artillery deployment. At Riga, von Hutier divided his 750 guns and 550 mortars to perform two distinct roles. These included the Infantrie Kampfzug Abteilung, or IKA, to provide direct infantry support, firing high-explosive and gas shells, and the Artillerie Kampfzug Abteilung, or AKA, which provided long-range fire to suppress the Russian artillery and disrupt their reserves and command structure. Von Hutier’s tactics proved so successful at Riga that he and Bruchmuller were reassigned to the Western Front, where they successfully applied them during the German April 1918 offensive.

The first modern equipment in the class was the 10.5-cm Feld Kanone (FK) 14, introduced in 1915. This was a box-trailed carriage with shield carrying a 35-calibre gun with sliding block breech, all made by Krupp. It formed a major proportion of the divisional heavy support during the First World War, though after 1917 it was supplemented by an improved version, the Model 17, which had a 45-calibre barrel and correspondingly better performance. These were backed up by the 15-cm Kanone 16, simply an enlarged model of the 10.5-cm weapon, and a 15-cm howitzer Model 13. This was the usual shorter-barrelled weapon firing a heavier shell and with the ability to lob the shell high in the air to drop behind cover.

German Field Artillery

Germany was decidedly behind France in field artillery development during the immediate prewar years. Constructed of steel and designed for use by the horse artillery, the light 80mm Model 73 field gun was an early attempt at producing a modern field piece. It employed a breech mechanism consisting of an expanding steel ring in the breech face against which a removable cylindrical breechblock pressed a steel plate to create a gas seal. Although a good weapon for its time, the Model 73’s breech mechanism wore out rapidly, it lacked a recoil mechanism other than wheel brakes, and it lacked sufficient range when loaded with shrapnel. Improvements in metallurgy and experimentation later allowed German designers to lighten the Model 73’s barrel. The result was the 90mm Model 73/88, which was then issued to both horse artillery and field batteries. After being refitted with nickel steel barrels, the design was finally redesignated the Model 73/91.

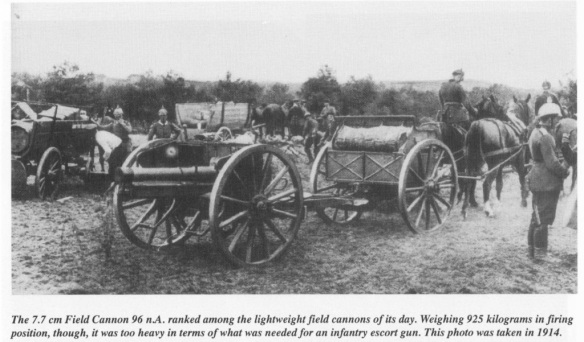

Although by no means a match for many more advanced foreign breechloaders, the 77mm Field Gun Model 96 (the Americanized form of the German Feldkanone M96) was at least an improvement over the Model 73/91 that it replaced. Adopted in 1896, it had improved horizontal sliding block and case extraction mechanisms as well as better sights and a capability of traversing 4 degrees to either side. Its design, however, did not adequately address controlling recoil, as it utilized only a wire-rope brake and a spade at the end of its trail that anchored it to the ground.

As the leading German arms producers, such as Krupp and Ehrhardt, found it more profitable to market their latest designs to Asian and Latin American governments, the German army found itself in the ironic position of fielding essentially obsolescent artillery. Rushed to provide a stopgap weapon in the face of foreign quickfiring advances, German engineers radically redesigned the Model 96 to produce the Model 96 New Model, the basis for German field guns for the next twenty years.

The New Model 96 shared the caliber, elevation capabilities, and range of the earlier model yet did incorporate a number of significant improvements. Weighing one ton, it had the ability to traverse to the left and right on its carriage, and it was equipped with a more efficient one-movement breechblock. More significantly, the barrel itself rode in a trough-like cradle, its recoil buffered by a hydraulic and spring-operated recoil device. The combination of the new model’s breechblock, fixed ammunition, and recoil system at last provided the German army with its own quick-firing field piece capable of a firing rate of about 20 rounds per minute. To protect the crew, who could now remain behind the piece during firings, the New Model also mounted a 4-millimeter-thick steel shield on either side of the barrel.

In addition to the M96, Germany also issued the 135mm FK 13, the 77mm FK 96/15, the heavy yet excellent 77mm FK16, and the 105mm K17. The improved 105mm Model FH98/09 howitzer incorporated an improved recoil system over the earlier FH98, and its box trail was fitted with an opening directly behind the breech to allow higher elevation of the barrel. Other field howitzers included the 105mm 1eFH16 and the 105mm FH 17.