On December 8, 1941-the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor-the VS-300 was first flown in its final configuration. By New Year’s Eve it was flying in all directions and handling better than ever. Meanwhile, the much larger Sikorsky XR-4 was being fitted with the same control scheme, and on January 14. 1942, the new helicopter was wheeled out of its hangar for a trial flight.

Four men hung on to the landing gear to prevent a premature lift-off as test pilot Charles Lester Morris checked out the engine and controls. Ready at last, Morris opened the throttle, raised the collective pitch lever and lifted off the ground. As Sikorsky stood below and waved. Morris stayed in the air for three minutes and then set down for some adjustments. The second time up, he remained aloft for a little more than five minutes before quitting for lunch. By the end of the day. Morris had made four more flights, logging 25 minutes of air time in the XR-4.

Sikorsky and his engineers continued to refine the XR-4’s design, and by May the craft was ready for delivery to the Army at Wright Field, in Dayton, Ohio. Les Morris flew the finished helicopter to its destination in 16 careful hops, taking five days but spending little more than 16 hours in the air. With Sikorsky beside him in the enclosed cabin, he would hover and check the route by reading highway signs or by asking information of a startled motorist. On one occasion he deliberately overshot the landing site and flew on for 100 feet. Then he slowly backed the helicopter to the spot and gently landed it. According to Sikorsky, one of the airport mechanics who had been watching from the ground remarked, “I don’t know whether I’m crazy or drunk.” Sikorsky and Morris touched down at Wright Field on May 17. The next day Orville Wright was among those who came to congratulate them.

In December, after running the new craft through extensive shakedown flights, the Army contracted for production to begin and also placed an order for a new, larger model. Four months later, in April 1943, it requested still another version. Sikorsky was clearly taking the worldwide lead in helicopter design and manufacturing. The Platt- LePage experimental model was not performing well enough to warrant a production contract, and in Germany, Allied bombing raids were disrupting the planned production of Henrich Focke’s Fa-223 and Anton Flettner’s nimble Kolibri-though Flettner’s machines saw limited service during World War II.

More than 400 Sikorsky helicopters would roll off the assembly lines by the end of the War. The novel craft would not alter the course of the conflict. Helicopters were still too limited in their capabilities. They lacked speed; they could carry only small loads, and when used at sea, they had difficulty operating from the windswept, pitching decks of warships. But then, in April 1944. Lieutenant Carter Harman of the U. S. Army Air Forces flew into the steamy jungles of northern Burma and proved that the helicopter had a definite military role to perform.

Harman, piloting a Sikorsky YR-4 (the X for experimental was replaced by a Y for a service-test model), had been summoned from his base in India to a secret outpost behind Japanese lines in the Burmese jungle. There, American forces were supporting British raiders who were seeking to reopen the Burma Road, a vital supply link between Allied forces in India and China. After following a circuitous 600-mile route to his destination, Harman received his orders: He was to pluck a stranded American pilot and three British casualties from the jungle 30 miles to the south. The pilot, flying a tiny L-1 liaison plane, had been bringing the Englishmen out when engine trouble forced him down. With no suitable landing strip nearby, the four men seemed doomed.

After watching Harman whirl down out of the sky for a vertical landing in a nearby paddy, the American L-1 pilot said to him: “You look like an angel!” But the angel faced a problem. The altitude, humidity and heat had thinned the air, sharply reducing the engine’s power and the rotor blades’ lifting capacity. Harman knew that the YR-4 could barely hover with only himself on board. His single hope was to jump abruptly aloft, then ease quickly into forward flight (one of the peculiarities of helicopters is that they need much more power to hover than to fly forward at moderate speeds), taking the men out one at a time.

With one of the injured Englishmen beside him in the cabin, Harman gunned the engine, revving his rotor to the limit, and pulled up on the collective pitch lever; the straining copter jumped nearly 20 feet above the paddy, quickly dissipating the stored-up kinetic energy in its rotor blades. Then Harman nosed forward to pick up forward speed and vaulted over some nearby trees. About 10 miles away, he unloaded his passenger in a dried-out riverbed from which L-5s could operate, then went back for the next rescue. After the second trip out, his engine became so dangerously overheated that he had to stop for the day, but he returned the next morning for two more lifts.

Harman performed several more such jungle rescues before returning to India two weeks later. The helicopter had shown that it could be a truly useful aircraft, a rotary-winged angel of mercy. In the years to come it would be that and more, in peace as well as war.

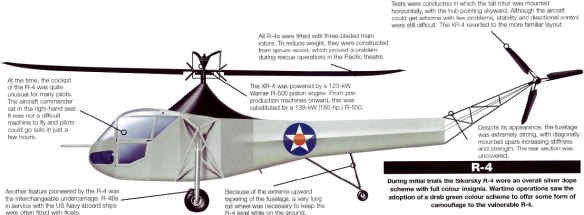

For the wounded on Luzon in 1945, the Sikorsky R-6A transport doubled as an ambulance. (38TH DIVISION PHOTOGRAPHER)

Because the R-4B had no external stretcher mounts, a removed a seat so an injured man could lie on the floor.(NASM 9A07871)

A pioneering rescue mission

In the closing months of World War II, the virtually impenetrable jungles of Southeast Asia provided a rigorous testing ground for the capabilities of the newly operational Sikorsky R-4 as a rescue vehicle. There, where dense foliage, precipitous terrain and the presence of the enemy often prevented the overland evacuation of the wounded, the ability of a helicopter to land and take off from a small clearing or a narrow riverbed meant the difference between life and death for many an Allied soldier.

A pilot, Captain James Green of the U. S. Tenth Air Force, had crashed just three minutes’ flying time from Shinbwiyang Air Field in northern Burma, but he was too badly injured to be carried back to base. In fact, once his plane was spotted from the air, it took rescue and medical teams a day and a half to reach him.

A helicopter was the only answer. However, the territory for miles around the crash site was so hilly and thickly forested that there was no spot for one to touch down. For two weeks, a detachment of combat engineers, a special Air Transport Command rescue crew and a group of Tenth Air Force volunteers labored to clear and level a nearby hilltop, using supplies and equipment dropped by air. When the landing area was ready, the rescue itself went so smoothly as to be almost anticlimactic. A Sikorsky R-4 picked up Captain Green early on the morning of April 4 and delivered him minutes later to the hospital at Shinbwiyang Air Field.