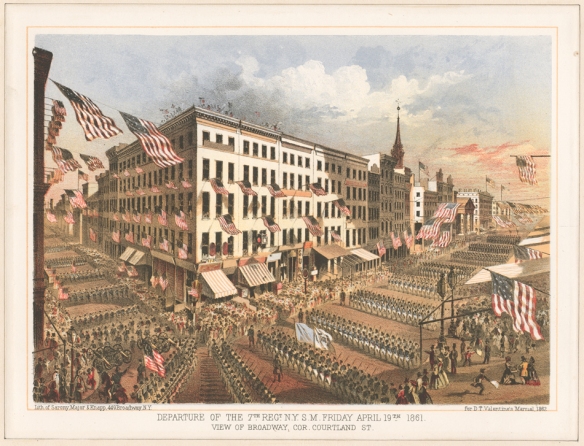

Cheered by thousands of well-wishers, soldiers of the elite 7th New York Militia parade down Broadway en route to Washington on the 19th of April, 1861. “It was worth a life, that march,” wrote a young private, who would pay exactly that price less than two months later.

Lincoln’s mainstay during the uncertain days of late April was Winfield Scott, the General in Chief of the Army. Scott had been a national hero since the infancy of the republic, had commanded the American army that won the Mexican War of 1846-1848, had served in the Army for 53 years and had been its top general since 1841. The handicaps of age, poor health and enormous bulk-Scott was almost 75, matched Lincoln’s height of six feet four and tipped the scales at almost 300 pounds-made it impossible for him to lead an army in the field; he had enough difficulty merely hauling his great weight up from his desk. But he stayed at that desk 16 hours a day during the crisis, calmly deploying his meager, motley forces in defense of Washington, planning strategy, sending frequent reports to the White House and doing the voluminous paperwork necessary to bring a genuine army into being. And although Scott conceded that the Confederate force of about 30,000 men at Charleston was larger than his whole army east of the frontier, he remained serenely confident that all would be well.

Because the new regiments were so slow to arrive. General Scott improvised a few colorful units of irregulars. One, made up of overaged veterans, was aptly called the Silver Grays. Another outfit was the Clay Battalion, formed and led by a rough-and-tumble Kentucky newspaper editor and politician named Cassius Marcellus Clay, whose vigorous support of Lincoln had earned him the post of Minister to Russia. Clay was in Washington waiting to depart for St. Petersburg when Sumter fell, and he went to the War Department to offer his services as an ordinary fighting man to Secretary of War Simon Cameron. “Sir,” said Cameron, “this is the first instance I ever heard of where a foreign minister volunteered in the ranks.” Said Clay, “Then let’s make a little history.”

Gathering some friends and associates, the Kentuckian formed his unit, which stood guard at the Executive Mansion and the Navy Yard. The Clay Battalion remained on duty until May 2, when Lincoln paid tribute to Clay and sent him off to Russia.

While Lincoln and Scott waited for the troop strength in Washington to build up, they were dealt repeated cruel blows by the defection of pro-Southern officers-a trend that had kept the Army in turmoil since South Carolina began the secession movement in December 1860. Many of West Point’s most brilliant graduates had felt that their first loyalty was to their home states, and had “gone South” to cast their lot with the Confederacy. Louisiana’s General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, commander of the siege of Fort Sumter, had been one of the first to defect, and he was followed by the Army’s highest-ranking active staff officer, Virginia-born Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston. In all, 313 officers-nearly one third of the experienced Regulars the Army possessed-resigned to take arms against the Union. The situation was nearly as bad in the Navy. Out of 1,554 officers of all ranks, 373-or almost one fourth-left the U. S. Navy, and most of them joined the Confederate Navy.

The defection that Lincoln and Scott regretted most deeply was that of Colonel Robert E. Lee. As an officer of engineers, Lee had served brilliantly under Scott in Mexico, and Scott had followed his career with almost paternal concern ever since. Lee was the first choice of Scott and the President to lead the Union armies into battle.

On April 18, Lincoln sent an emissary to sound out Lee and judge if he would accept the command. Lee listened politely and expressed the belief that “I look upon secession as anarchy.” If he owned every slave in the South, he would “sacrifice them all to the Union.” But, he sadly concluded, “how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native state?” He would return to his home at Arlington House, just across the Potomac, “share the miseries of my people and save in defense will draw my sword on none.”

After this interview, Lee went to see his friend and mentor, Scott. It was a tearful moment for them both. “Lee,” said the aged general, “you have made the greatest mistake of your life, but I feared it would be so.”

A number of Southern officers remained loyal to the United States-and paid a high price for their choice. Major George H. Thomas of Virginia, who was to become one of the Union’s best generals, was reviled and disowned by his own family when he refused to resign his commission. General Scott, himself a Virginian, suffered cruelly for his allegiance to the Union. When the Old Dominion declared for secession on the 17th of April, many Southerners assumed that Scott would join the Confederacy, and Governor Letcher even smuggled a delegation of Virginians into Washington to discuss with Scott his expected defection. The general cut their spokesman off in midsentence. “I have served my country, under the flag of the Union, for more than 50 years,” he said, “and so long as God permits me to live, I will defend that flag with my sword, even if my own native state assails it.”

Scott’s decision stirred up a storm of Southern vituperation. “With the red-hot pencil of infamy,” raged an editorial in the Abingdon, Virginia, Democrat, “he has written upon his wrinkled brow the terrible, damning word, ‘Traitor.’” In Charlottesville, students at the University of Virginia burned him in effigy. His nephew tore the general’s portrait from the wall of the family home and ordered his slaves to chop it up and throw it into a millpond.

Of much greater concern to General Scott was the situation in Baltimore, which failed to improve despite the President’s chary decision to bypass the city. A secessionist cut the telegraph wires from Baltimore southward, forcing Washington to rely for a while on a single line westward. Baltimore Police Marshal Kane sent out messengers in all directions to raise secessionist sharpshooters and hustle them back to town. The British consul in Baltimore reported, “The excitement and rage of everyone, of all classes and shades of opinion, was intense.”

But the secessionists failed to discourage that reckless opportunist from Massachusetts, Benjamin Butler. On April 20, General Butler was in Philadelphia with his 8th Massachusetts. He heard of the violence in Baltimore and, unable to communicate with Washington, deduced that Baltimore was impassable. Clearly he had to find a way around that city. It did not take him long. He and the Massachusetts men went by train to Perryville on the banks of the Susquehanna, commandeered a big ferryboat and sailed down to Annapolis. So far so good.

Butler’s plan was to travel on the Annapolis & Elk Ridge Railroad from Annapolis to Washington. However, secessionist officers of the line saw to it that a little hitch developed. To stop Butler, they sent their locomotives out of town and had work gangs tear up the rails behind them. But Butler discovered a broken-down locomotive in an abandoned shed and, on asking if anyone in his command could fix the engine, received a singularly gratifying reply. A private took a look and said, “That engine was made in our shop; I guess I can fit her up and run her.” The private did so. In the meantime. Secretary of War Cameron and Thomas A. Scott, Vice President of the Pennsylvania Central Railroad, assembled a group of trained railroad men-including a young Scot named Andrew Carnegie-and the railroaders repaired the tracks. The first trainload of troops chugged off toward Washington on April 25.

That day started out in doleful fashion in the capital. The news from all points was bad, and General Scott was preparing to issue an alarm saying, “From the known assemblage near this city of numerous hostile bodies of troops it is evident that an attack upon it may be expected at any moment.” But instead of an attack, the city received, at about noon, the men of Butler’s 8th Massachusetts and the crack 7th New York. Cheered with fraternal pride by the 6th Massachusetts and with almost hysterical relief by the citizens of Washington, the New Yorkers and the Massachusetts men paraded up Pennsylvania Avenue and past the White House grounds. President Lincoln came out to wave to them and, said an aide, “He smiled all over.”

The logjam had been broken; henceforth 15,000 men a day could travel the rail line from Annapolis to Washington, and it no longer mattered so much what happened in Baltimore. But a great deal more did happen in Maryland, and once again the venturesome General Butler played a leading role in the events.

On April 26, Governor Hicks called the Maryland legislature into session at Frederick, 50 miles west of Baltimore and 18 miles northeast of Harpers Ferry. There was still a danger that secessionist agitators might panic the legislature into taking Maryland out of the Union. Frederick itself was a key point in Maryland, lying athwart the Baltimore & Ohio rail line to Harpers Ferry and the route to and from the Shenandoah Valley.

To neutralize Frederick, General Scott decided that a railway junction eight miles from Baltimore on the line to Frederick should be seized and held by Federal troops. He ordered General Butler to take the junction- called Relay House, after a local hotel -with his Massachusetts men. At about the same time, Union troops closed in on Baltimore, reinforcing Fort McHenry and garrisoning Fort Morris, and construction crews went to work restoring the sabotaged railroad bridges.

Butler’s sortie to Relay House turned out to be easy. On May 5, he and the 6th Massachusetts traveled north from Washington by rail, occupied the junction and emplaced artillery batteries. In the following days, other Massachusetts units arrived at Relay House to reinforce Butler, but they were not needed. Relay House was so dull, in fact, that Butler quickly lost interest in his assigned mission. The general’s natural instinct for sensation drove him toward Baltimore. Although the city had quieted down considerably since the rioting in mid-April, the secessionists there were still restless-so much so that Lincoln authorized preventive arrests and the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus along the rail line.

Butler, disdaining to seek General Scott’s permission, launched a bold but complicated coup from Relay House on May 13. First, for deception, a troop train traveled west into Frederick, and along the way the men arrested the noted secessionist agitator Ross Winans. Then the train retraced its path past Relay House and steamed into Baltimore, Butler’s men piled out at the Camden Street station and occupied Federal Hill, overlooking the city’s ship basin. Since the Yankees arrived under cover of a violent thunderstorm, their presence was barely noticed by the Baltimoreans until the next morning, after the skies had cleared. When the citizens came outdoors, they were astonished to find nearly 1,000 Union troops and a battery of artillery glowering down at them from the harbor heights. The secessionist jig was nearly up in Baltimore.

Scott reproved Butler for acting without orders and removed him from his post. But nearly every Northerner was grateful to Butler. Though the political general had run the risk of sparking a nasty incident in Baltimore, he had faced down the secessionists with a fine show of vigor and daring-this at a time when both were in short supply in the Federal military.

Washington was now secure as the forward base for Union troops pouring in from all over the nation; thanks to the strong and prompt Federal action, there was no need to fight battles for Maryland. As a result, the armies of the Union and the Confederacy would fight out most of the great battles of the War in the 100-odd miles of rough terrain between Washington and Richmond.