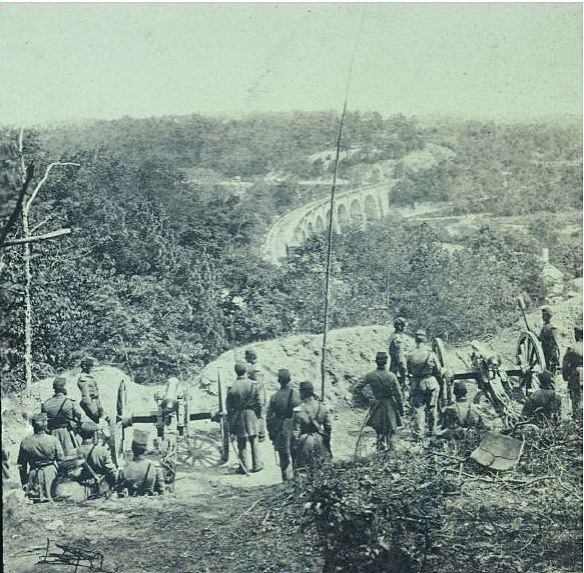

Federal artillerymen, guarding a railroad bridge near Relay House, watch for troublemakers from secessionist Baltimore, eight miles to the north. Their commander, General Benjamin F. Butler, had no fear of an attack, declaring that he had never seen “any force of Maryland secessionists that could not have been overcome with a large yellow dog.”

Struggling with a huge timber, troops of the Washington-bound 8th Massachusetts and 7th New York rebuild a sabotaged railroad bridge at Annapolis Junction, Maryland, reopening the route to the capital.

The city of Washington, whose population had reached 61,000 in 1860, spent the first two weeks of the War teetering on the brink of panic. Lucius E. Chittenden, a Vermont banker and prominent Lincoln supporter who arrived in the capital on April 17 to serve as Register of the Treasury, found every main thoroughfare blocked and guarded; he wrote that Washington wore “the aspects of a besieged town” and was “filled with flying rumors of various descriptions.” One wild report told of ships steaming up the Potomac loaded with Rebel cutthroats. Other tales had it that 5,000 armed men, or even 10,000, were on their way to attack the city or hijack the federal government.

Chittenden, whose sense of the Union’s strength had been bolstered by the fervent patriotic displays he had seen in Northern cities on his journey south, was jolted to find that his government was weak, frightened and ill-prepared to defend the capital. No more than 1,000 troops of the nation’s scattered 13,000-man Regular Army were on hand; they had the backing of 1,500 militiamen, but this number included many Southern sympathizers who were considered untrustworthy. For Chittenden, the greatest shock came on April 18, when he was assigned to help issue weapons and ammunition to the Treasury clerks in case of an enemy attack. Because the Treasury Building was considered Washington’s strongest, it had been decided that Lincoln and his Cabinet would take refuge there during any Confederate assault, and Chittenden realized with horror that he might be called upon to defend his President with his own hands.

In fact, the capital stood in no immediate military peril. Any serious attack on Washington would require a substantial amount of manpower and equipment-plus time to organize, train and mount the expedition. The governments in Richmond and Montgomery simply were not ready.

Nonetheless, Washington was in real danger- albeit danger of another kind, and from the opposite direction. The 10-squaremile District of Columbia was pinned against the Potomac and engulfed on all other sides by Maryland; if that state joined Virginia in secession, Washington might well lose its land routes and communication links to loyal states in the north and west. The Union could hardly function well without its head.

Moreover, Northerners had little reason to think that Maryland would stay in the Union. Marylanders did more than one third of their business with their fellow slave states. And there was alarming evidence of the state’s disenchantment with the Union. In the presidential election of 1860, Abraham Lincoln, running on his save-the-Union pledge, received fewer than 3,000 of the 92,000-odd votes cast in the state; the city of Baltimore, where rail lines from the north and west connected with the single line to Washington, gave Lincoln just a little more than 1,000 of its 31,000 votes. To some ex-tent, the figures were deceptive: Most Marylanders probably preferred the Union to the Confederacy. But pro-Union Marylanders, among them the vacillating Governor Thomas H. Hicks, were apparently intimidated by the more militant secessionists, who were strongest around Baltimore, in central Maryland and on the Eastern Shore.

Actually, it made no difference whether Washington was endangered from the south or from the north; the best counter to both threats was to bring soldiers to the capital, as many as possible and as soon as possible. On the day Lincoln sounded the call to arms, he voiced a special appeal for troops to the nearby state of Pennsylvania and was quickly obliged with a token shipment of a few hundred men.

It was questionable, though, whether the Pennsylvanians’ arrival from Harrisburg on April 18 was more reassuring than alarming. Most of the men were unarmed and poorly trained. Worse, they told cautionary tales of their trip through Baltimore: A jeering mob of secessionists had pelted them with rocks and paving stones. In any event, the Pennsylvanians contributed handsomely to the bizarre makeshifts that war foisted on Washington. Since there were no barracks in the city, the troops were quartered in the Capitol and were fed meals from an emergency kitchen set up in the basement.

The next regiment scheduled to reach Washington was the 6th Massachusetts Infantry. This volunteer unit was one of four that had been drilling in the Bay State for several months on the assumption that the secession of the Southern states had made war inevitable. The regiments’ commander was a brilliant, unscrupulous and exceedingly powerful Lowell attorney named Benjamin F. Butler, who had tirelessly helped organize these militia units but had never led so much as a squad into battle. It was then standard practice for a governor to reward or solicit important backers with appointments to high posts in the state militia, regardless of their military qualifications. On both sides, but especially the North, many political generals who took to the field would prove to be a curse.

Word of his appointment by Massachusetts Governor John Andrew reached Butler while he was in the midst of a trial. “I am called to prepare troops to be sent to Washington,” the brand-new brigadier general announced importantly in the courtroom, and the case being argued was postponed, never to be finished. Directing operations from Boston, Butler shipped two of his regiments to strategic Fort Monroe near Hampton Roads, Virginia. Then, leaving the 8th Massachusetts at home to complete its organization and equipping, he sent the 6th Massachusetts to the capital under the command of Colonel Edward F. Jones, a 32-year-old former businessman from Utica, New York.

Jones and his regiment boarded a train for New York on April 17 and arrived the next day to a tumultuous reception. The men marched down Broadway, cheered by thousands, then were treated to a lavish meal at the Astor House. That night they continued their journey via Philadelphia, intent upon completing the trip to Washington on the morrow. Some time before Jones loaded his regiment on 10 coaches in the Philadelphia rail yards in the early hours of April 19, he received word of the hostile reception Baltimore had given the Pennsylvanians. He distributed ammunition and ordered his men to load their weapons.

The train reached Baltimore’s President Street station around noon. This was the terminus of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore line, and for travelers bound farther south, horses would pull their railroad cars over a track through the city to the Camden Street station, where the Baltimore & Ohio line to Washington commenced.

At the President Street station, Colonel Jones made a critical mistake. Instead of detraining his 800-man regiment and marching it in a compact column through the city, he instructed the troops to ride their slow-moving coaches to Camden Street. As a result of this order the soldiers were sitting targets, with no opportunity for quick deployment or maneuver. Moreover, the regiment could be split up.

The first seven cars arrived at Camden Street quickly and without mishap. But the last three cars were slowed down by a crowd that grew to perhaps 8,000 as the citizens learned what was happening. At Pratt Street, the mob halted the horses, and the Bay Staters were forced to pile out and march for their lives. Before long the men were hurrying through a hail of missiles. Soon bystanders began to wrestle with them, wrenching their muskets from their hands. Then pistol shots rang out.

Moments later, a soldier in the front rank fell, killed by a civilian’s bullet. At that, the officer in charge ordered his men to return fire. Their fusillade cut a path through the mob, and the companies completed the march at a quickstep, helped rather tardily by the pro-secessionist Baltimore police.

At the Camden Street station. Colonel Jones was enraged by the rattle of gunfire, and as his beleaguered rear elements rejoined him, he tried to form the regiment for an attack on the mob. Cooler heads dissuaded him, however, and the troops crowded aboard the railroad cars bound for Washington. A locomotive was attached, and they set off for the capital, leaving behind three soldiers and 12 civilians dead, more than 20 troops injured and 130 unaccounted for. When the train finally pulled into the capital at 5 o’clock in the afternoon, Lincoln himself was there to meet it. Shaking Jones’s hand, he said, “Thank God you have come.”

Lincoln’s problems with Baltimore and Maryland were not over-far from it. Governor Hicks, buckling under to secessionist leaders, agreed that the best way to keep the peace was to keep the troublesome Yankee troops out of the state. Gangs of secessionists quickly acted on this conclusion, demolishing four railroad bridges leading to Baltimore. The destroyed bridges, together with the losses suffered by the 6th Massachusetts in transit, temporarily halted Lincoln’s efforts to squeeze troops through the Baltimore bottleneck. Reinforcements for Washington would have to come by another route.

The most promising alternative was to send regiments by ship from northern ports to Annapolis, on the Chesapeake Bay 20 miles south of Baltimore. From there the troops could march overland 40 miles to Washington. Embarkation orders went out to the 7th New York, a fine parade regiment, and several units from Rhode Island.

Hearing of this, Maryland secessionists threatened to block the new route, and when representatives were called to the White House, they demanded that Union soldiers cease defiling the state’s sacred soil. Lincoln refused. “I must have troops for the defense of the capital,” he told the delegation, which included Mayor George W. Brown of Baltimore and the Police Marshal of Baltimore, George P. Kane. Lincoln went on, “Our men are not moles and can’t dig under the earth; they are not birds and can’t fly through the air. There is no way but to march them across, and that they must do.” He concluded with a lame warning: “Keep your rowdies in Baltimore and there will be no bloodshed.” In other words, the President of the United States had no choice but to abandon Maryland’s first city to secessionist rabble in the hope of quarantining the state’s rebellion.

The sea-land route was long and slow, and days passed in Washington with no sign of the promised regiments. The President was frequently seen by his secretaries anxiously pacing about his office, and he was heard muttering, “Why don’t they come? Why don’t they come?” During a visit to the men of the 6th Massachusetts, who were billeted with the Pennsylvanians in the Capitol, the President uncharacteristically allowed his frustration to show in public: “I don’t believe there is any North!” he exclaimed. “The 7th Regiment is a myth! Rhode Island is not known in our geography any longer! You are the only Northern realities!”