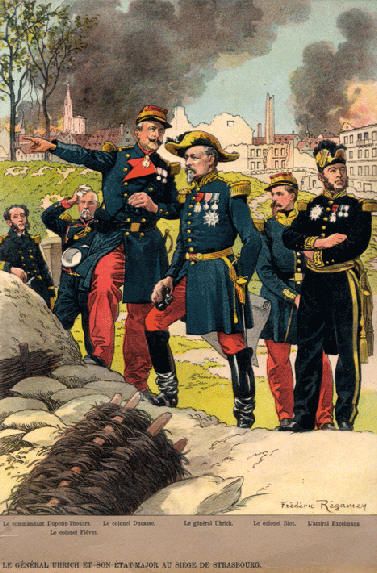

French staff at the siege of Strasbourg 1870.

Charge of the French Cuirassiers, Franco-Prussian War.

Confidence in an early French victory ran high. At the height of the crisis La Liberté, mouthpiece of Émile de Girardin, pioneer of the cheap press in France, crowed that ‘If Prussia refuses to fight we shall boot her back across the Rhine with our rifle butts in her back and force her to yield the left bank.’

A more temperate newspaper complained that ‘they talk about crossing the Rhine as if it were as easy as strolling across the Seine bridges’. Yet the high command initially shared in the general mood. On several occasions during the critical days of 14 and 15 July Marshal Edmond Le Bœuf, who as War Minister was the highest authority in the French army below the emperor, assured the Imperial Council and the Chamber that the army was absolutely ready. His confidence, his insistence that France must seize her opportunity by striking first and his urging of mobilization underpinned the French decision for war. Adolphe Thiers, one of the few Deputies with the courage to argue against declaring war, testified that:

At that fatal epoch, one phrase pervaded every conversation and was on every lip: ‘We are ready! We are ready!’ … There are moments in our country when everybody says a thing, repeats it, ends up believing it and, with every fool joining in, the pressure of the crowd overpowers all resistance … [This phrase] was first heard from Marshal Niel, and daily from Marshal Le Bœuf, and was no more true under the one than the other.

The army of the Second Empire certainly made an imposing sight, as the crowds who watched it on parade at its annual reviews at Châlons Camp every summer could testify. A march-past of over 30,000 men in front of the emperor, the Tsar of Russia and King Wilhelm of Prussia in Paris at the time of the Universal Exhibition in the summer of 1867 prompted the recollection that

At that time the French army had a rather ‘showy’ appearance. The tight frogged jackets of the grenadiers and light infantry of the Guard, the shakos with horse-hair tufts and short tunics of the line infantry with their yellow puttees gave the impression of theatrical costumes rather than battledress. However, in the mass these refinements were lost, and you saw only the thousand colours of an infinite variety of uniforms which led you to believe that far more men were present than was actually the case.

In 1870 the combatant arms of the French army consisted of one hundred regiments of line infantry, dressed following the 1867 regulations in blue coats, red trousers, white gaiters and red-topped kepis, together with twenty battalions of light infantry (chasseurs-à-pied) dressed in dark blue, fifty regiments of cavalry (10 of cuirassiers in their steel breastplates and helmets, 12 of dragoons, 8 each of lancers and hussars and 12 of light cavalry (chasseurs-à-cheval)), twenty regiments of artillery and three of engineers. The Imperial Guard, revived by Napoleon III in 1854, was an elite force which drew the best soldiers from the line regiments and enjoyed higher pay. It formed in effect a self-contained army corps with regiments of all arms – eight of infantry plus one battalion of light infantry, six of cavalry and two of artillery. More exotically clad still were the troops of the Army of Africa based in Algeria. Its infantry comprised three regiments of Zouaves in their short jackets, baggy trousers and tasselled fezzes; three regiments of Algerian sharpshooters (tirailleurs) known as Turcos – native troops with white officers; the Foreign Legion and the Zéphyrs – the latter delinquent types being punished for offences against military discipline. The cavalry of the Army of Africa was composed of four regiments of the famous (or to Mexicans infamous) African Light Cavalry (chasseurs d’Afrique) in their sky-blue jackets and tall caps; and three regiments of Spahis – native cavalry wearing Arab hooded cloaks.

The army was eager for war, which after all was its raison d’être. Officers looked forward to a campaign which would provide opportunities for decorations through feats of valour, and in which casualties would open the way to promotions that in peacetime depended largely on having the right connections. The victories of the last two decades reinforced confidence that they were the best army in the world and ‘had nothing to envy in a foreign army, nothing to borrow from it, and nothing to learn from it’.

Nevertheless, when pitted against an opponent more formidable than the Russians or Austrians, the French army proved to be dangerously inferior in strength, organization, war-planning, training and artillery. Budgetary constraints had kept troop numbers well below establishment since the Italian war. In 1870, 434,000 men were nominally serving with the army, but when the results of the plebiscite on constitutional reform were published in May they showed that only 300,000 men were actually on duty. Of these, France maintained 64,000 in Algeria and 5,000 at Rome. Awareness of French weakness was an element in the German decision for war.

Yet the size of her peacetime regular army was not the fundamental source of French weakness measured against the 304,000 strong standing army of the North German Confederation, or 382,000 if the South German states are included. The crucial difference between the opponents was that on the outbreak of war Germany could call upon a huge pool of fully trained reserves whereas France could not. In 1862 Prussia had adopted a system of universal military obligation whereby men aged 20 were conscripted into the army for a relatively short three-year term of service, but thereafter remained in the reserve for another four years and were subject to another five years’ service in the Landwehr, a territorial force whose role was to relieve the regular army by manning fortresses, guarding communications and maintaining internal order. After 1866 the Prussian system was extended to the North German Confederation and in modified form to her South German allies. Following a carefully prepared mobilization plan, by the first week of August 1870 the Germans had massed three armies on their western frontier with a combined strength of 384,000 men, excluding non-combatant troops. Facing them, by 1 August the French had assembled only 262,000 men, including officers and non-combatants, despite Le Bœuf’s promise to the emperor on 6 July that he could put 350,000 men on the frontier within a fortnight of the order to mobilize.

This disparity was due not only to defects in French plans for mobilization and transportation, but to her rejection of the sacrifices required by universal military service. Napoleon III intended the army reforms he initiated in 1866 after Sadowa to give France as large an army as Prussia, but parliamentary opposition emasculated the plan. The Left feared that if the emperor were given a larger army war would become more rather than less likely, as had been the case under his uncle. They mistrusted the army as the compliant instrument of the 1851 coup d’état, feared its increased use for the suppression of liberty at home, and pointed accusingly at Napoleon’s record of military adventures in Mexico, Italy and China. They preferred a citizen militia that could be used solely for defensive purposes. ‘These gentlemen,’ wrote Mérimée, who was close to the imperial family, ‘would willingly leave France defenceless against foreigners so that power might fall into the hands of the rabble-rousers of the Paris suburbs.’ The issue between the Left and the government, and the enduring dilemma for France, was epitomized during the debate on the new army law, sponsored by the then War Minister, Marshal Niel, in January 1868. Leading republican Jules Favre shouted at the minister, ‘Do you want to turn France into a barracks?’ Niel turned and responded in a low voice that would send a chill echo down the following decades of French history: ‘And you, take care that you don’t turn it into a cemetery.’

But opposition to the new law was not confined to the pacifist and anti-militarist Left. Many conservative army officers were contemptuous of the idea of a hugely inflated army composed of short-service conscripts, which in their view would lack the proper military spirit of an experienced regular force, and would be unreliable for maintaining order at home. Thiers, who as a historian of the First Empire considered himself an expert on military matters, ridiculed the idea that Prussia could put over a million men into the field. Deputies loyal to the government were swayed by the intense unpopularity of conscription in the country, and its likely impact on their chances of re-election.

Under the existing system Frenchmen had many chances of avoiding military service when they reached the age of 20. Conscription of the annual contingent – generally set at 100,000 but often much lower in practice for budgetary reasons – was decided by drawing lots. Men who drew a ‘good number’ did not have to serve. Even those who drew a ‘bad number’ could buy themselves out of service, and could even take out insurance for the purpose. A law of 1855 had allowed military service to be commuted for payment of a fixed fee to the government. The money raised was used to pay re-enlistment bounties to serving soldiers whose terms were due to expire.

The effects of this system were that the wealthy could buy themselves or their sons out of the army, leaving its ranks to be filled by the poorest classes. Roughly a quarter of infantry conscripts were illiterate. Nor did the number of men induced to re-enlist ever equal the number who had bought themselves out. The re-enlistment of NCOs under the bounty system encouraged long service, but at the price of pushing up the average age of sergeants and corporals who too often were well past their best and had acquired the bad habits of old soldiers. Lacking the potential for promotion to the officer corps themselves, they blocked the promotion prospects of younger and more able men.

The French army was in some respects the most open to merit in Europe, for by law one-third of junior officer vacancies had to be filled by promoting NCOs from the same unit rather than directly from the officer training schools. That in practice nearly two-thirds of officers had been promoted from the ranks bore witness to the army’s failure to attract enough suitable candidates into the officer schools. Compared to Germany, where all officers had to pass through a military academy, standards of education among French officers outside the technical arms remained generally low: ‘to get on one had above all to have a good physique, good conduct and a correct bearing’. Slavish obedience to regulations was valued more highly than theoretical study, which was rather frowned upon. Poor pay, slow promotion and restrictions on marriage made life in overcrowded barracks an unattractive prospect to ambitious young men, particularly at a time when commercial prosperity offered more lucrative opportunities elsewhere. Military service was widely seen as a stroke of bad luck, to be avoided if all possible. Nothing so alarmed the Deputies debating the new conscription law than the prospect that ‘there will be no more good numbers’.

Thus the new army law was only passed in February 1868 after long and divisive debates, and fell far short of its goal. The period of service was increased from seven years to nine, though the last four would henceforth be in the reserve. Although the system of cash commutation introduced in 1855 was ended, draftees were allowed to hire substitutes and the Legislature insisted on retaining its right to fix the size of the annual contingent. Niel’s idea of forming a vast trained reserve of all men who had hitherto escaped military service, whether by drawing a ‘good number’ or by exemption or early discharge, was rendered virtually useless by the restrictions on its training imposed by the Legislature. This new force, the Garde Mobile, was limited to a fortnight’s annual training with no periods of more than 24 hours away from home. Nor could it be mobilized in wartime without the passage of a special law. After attempts to muster it provoked local disorders, Niel’s successor Le Bœuf lost interest in the institution, preferring to spend the limited funds available on the regular army. When war came suddenly in 1870 the effects of the Niel law had yet to bear fruit, and France would pay a grievous price for declining to provide herself earlier with a sufficiently large and well-trained reserve.

France preferred to believe that quality would tell over quantity, and her leaders put great faith in her new weapons. In the wake of the Prussian victory over Austria Napoleon had ordered the introduction of the Chassepot model 1866 as the standard infantry weapon. This breech-loading rifle was accurate and robust, with a range of 1,200 metres – more than twice that of the Prussian Dreyse ‘needle gun’ which had been in service for three decades. The bolt action of the Chassepot allowed the trained soldier to fire up to seven shots per minute. The advantages of fighting the Germans before they could introduce a new rifle of comparable quality were not lost on Le Bœuf. Already the Bavarians were introducing the 1869 model Werder rifle which was superior to the Dreyse.