U-119

The new VII U-449, commanded by Hermann Otto, age twenty-nine. On June 14, a B-24 of British Squadron 120, piloted by Samuel E. Esler, which was escorting Outbound North (Slow) 10, inflicted “slight damage” to the boat. When Otto reported that he urgently required a doctor to tend his wounded, U-boat Control directed the veteran VII U-592, commanded by Carl Bonn, age thirty-two, which, as related, had sailed from France in the last days of May with a doctor, to close U-449’s position at maximum speed. On the chance that this meeting might fail, Control ordered Otto in U-449 to abort to France at maximum speed and to join two other boats inbound to France, including the big Type XB minelayer U-119, commanded by Horst-Tessen von Kameke, age twenty-seven, who was returning from a mine-laying mission off Halifax and also had a doctor on board. The U-119 had just given the new tanker U-488, commanded by Erwin Bartke, all possible spare fuel and Otto in U-449 found U-119 before U-592 found him. Otto obtained the necessary medical assistance from U-119, then commenced a crossing of Biscay in company with her.

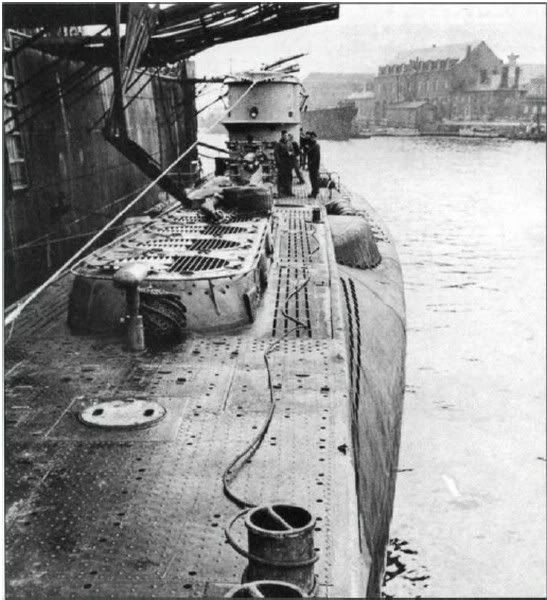

As part of the saturation ASW campaign in the Bay of Biscay, the Admiralty had assigned Johnny Walker’s Support Group 2 to patrol the western edge of the Bay of Biscay, in cooperation with Coastal Command aircraft. Early on the morning of June 24, Walker in the sloop Starling got sonar contacts on U-119, while some other ships of the group got sonar contacts on U-449. Walker immediately attacked U-119, dropping ten depth charges that brought the U-boat to the surface with “dramatic suddenness.”

All warships that could bring guns to bear opened fire, but after one friendly shell hit Starling in the bow, Walker ordered the others to cease fire while he rammed. He smashed into von Kameke’s U-119 solidly, riding up over her forward deck and capsizing her. The impact bent Starling’s bow 30 degrees off kilter, wiped off the sonar dome, and flooded the forward ammo magazine. For added insurance, Starling and the sloop Woodpecker each fired another salvo of depth charges. For proof of a kill, Starling’s whaleboat collected “locker doors and other floating wreckage marked in German, a burst tin of coffee and some walnuts.” There were no survivors of U-119.

Thereafter four sloops of this group, Kite, Wild Goose, Woodpecker, and Wren, ganged up on Otto in U-449. Exchanging commands with D.E.G. (Dickie) Wemyss in Wild Goose, Walker led these four warships in renewed attacks. They hunted and depth-charged U-449 for six hours before wreckage and oil rose to the surface, giving proof of a kill. There were no survivors of U-449 either.

Having sunk two confirmed U-boats in one day, Walker’s group followed the damaged Starling into Plymouth, where there was a stack of congratulatory letters from First Sea Lord Pound, Max Horton at Western Approaches, and others down the chain of command. For his part, Walker-undisputed king of the U-boat killers-sharply criticized the lack of cooperation the Coastal Command aircraft had shown his ships.

#

The North Atlantic boats were supported in September and October 1942 by five U-tankers. These included two Type XIV “Milk Cows,” Wolf Stiebler’s U-461 and Leo Wolfbauer’s U-463, and three big Type XB minelayers on temporary tanker duty: the U-116, commanded by a new skipper, Wilhelm Grimme, age thirty-five, which sailed on September 22 and disappeared without a trace, probably the victim of an as yet unidentified Allied aircraft; the new U-117, commanded by Hans Werner Neumann, age thirty-six, who first laid a non-productive minefield off the north-western coast of Iceland; and the new U -118, commanded by Werner Czygan, age thirty-seven.

All the U-boats sailing in September and October were equipped with the meter-wavelength FuMB radar detector made by Metox. The primitive but remarkably successful Metox (“Biscay Cross”) reduced U-boat losses, damage, and delays in crossing the Bay of Biscay to such a marked degree that on October 1 the British cancelled the intense ASW aircraft offensive in the bay. But Metox gear was not able to detect centimetric-wavelength radar, which was fitted in the British surface escorts and the long- and very-long-range aircraft in the North Atlantic area. Although few in number, those radar-equipped aircraft were able to catch U-boats by surprise, disrupt numerous group attacks, and sink or damage an ever-increasing number of U-boats.

#

Leaving from France, Hans-Joachim Schwantke in the aging IX U-43 and Hermann Rasch in the XB U-106 arrived in Canadian waters first. Both reported intense air patrols. Rasch likened them to the air threat in the Bay of Biscay. Newly installed Metox gear gave warning of aircraft using meter-wavelength ASV radar, but Rasch, who dived and surfaced U-106 so often that he felt like a “dolphin,” suggested that if at all possible, Metox should be upgraded to provide the range to the detected aircraft.

Both Schwantke and Rasch cruised boldly up the St. Lawrence River Schwantke farther upstream that any U-boat skipper ever had-but attentive air patrols and noticeably improved cooperation between air and surface ASW forces thwarted attacks on convoys and single ships. Moreover, it was at about this time that Canadian authorities closed the St. Lawrence River to ocean shipping. In these arduous, nerve-racking operations, Schwantke sank no ships and Rasch sank but one: the 2,100-ton ore boat Watenon, escorted by the armed yacht Vison and an RCAF Canso. After the attack, Vison got U-106 on sonar and dropped twelve well-placed depth charges, forcing Rasch to lie doggo on the bottom at 607 feet for eight hours. Upon withdrawing from the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Schwantke advised Donitz that Canadian ASW measures were now so effective that he should not send any more boats to the area. Rasch concurred, but Donitz did not.

Harassed by aircraft, neither Schwantke nor Rasch had any further success. Homebound, the boats were to meet the tanker U-460, commanded by Ebe Schnoor, for replenishment. A raging storm delayed the refuelling for six days, during which time they-and some other U-boats-literally ran out of fuel and drifted. Finally the refuelling was carried out on November 29 and most of the boats returned to France, but Rasch in U-106 was temporarily diverted to help repel the Torch invasion convoys. For past successes and for his tenacity and aggressiveness in the St. Lawrence River, Donitz awarded Rasch a Ritterkreuz.