A couple of weeks later 13 Mira was ordered back onto the Crete run. This time the task was harder — to cross the width of the island and bomb Souda Bay near Chania, where German warships and supply ships were berthed. Stratis led eight bombers on this operation. The squadron was supposed to rendezvous with a South African and Australian squadron at about the same time. When 13 Mira arrived, though, the sky over Crete was already black with fighters and flak bursts — the other two squadrons had got there early. Gritting his teeth, Stratis gave the order: ‘Turn to starboard, dive and bomb individually.’ One by one, the Greek planes peeled off and unloaded their high explosives onto the German ships.

In the middle of his dive through the deafening flak, Pattas heard something metallic hit his plane. Unknown to him, it was an unexploded flak shell that had penetrated the fuselage between the wireless operator’s seat and the British upper gunner’s position, and was rolling back and forth on the floor as the plane bucked and weaved. It was supposed to be common knowledge that flak shells either exploded on impact or not at all, but the wireless operator kept a wary eye on it. Pattas, meanwhile, started his own bombing dive a bit steeply. When he pulled up sharply he blacked out for a few moments. He came to, finding himself still flying north, with several Messerschmitts on his tail, and so made a sharp about-turn over western Crete, shaking off the fighters. When the Baltimore made its belated landing the nervous wireless operator jumped out first. ‘There’s a shell in plane!’ he yelled. That was the first Pattas knew of it. The projectile was soon neutralized.

Crete, bristling with German flak, was proving a tougher proposition than expected. To minimize losses the RAF Middle East command changed tactics. From now on, smaller formations of three aircraft each would attack Souda at low level from the seaward side. Stratis didn’t think much of the idea. In his view, losses would rise rather than fall, as the bombers would be turning in over the sea in plain view of the defences instead of weaving through the Cretan hills. In fact, it would be bloody suicide. But when orders for the first operation with the new tactics came through, Stratis felt honour-bound to lead it as an example to his crews.

Pattas protested. ‘It’s my turn, sir, and anyway, you’re married with children,’ he told his commander.

As Stratis blinked back tears, wondering what to do, the RAF liaison officer present got in touch with 201 Wing headquarters to see what it thought. ‘I aven’t got the luxury,’ Stratis told headquarters on the phone, ‘to lose crews applying tactics I don’t believe in.’ 201 Wing agreed.

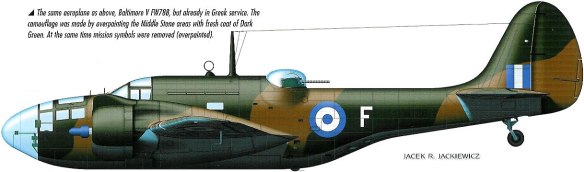

The Greeks enjoyed flying the Baltimore, especially when the rugged American attack bomber left the Luftwaffe’s fighters panting behind. To be able to fly it well, the crews of 13 Mira had to take a short conversion course. One newly arrived officer, Squadron Leader Dimitrios Dritsas, a former seaplane pilot, felt he knew enough not to have to take the course. Accordingly, when he took the controls of a Baltimore at Derna and attempted to take off, the powerful plane slewed off the runway, shearing off the undercarriage and slamming into the sand. As the plane was fully bombed up, the three other crew members leapt out of the plane. One of them tried to pull out Dritsas who was fumbling with the unfamiliar harness while flames licked at the cockpit. At that moment an RAF fire engine sped up and the three crew members were ordered away. Dritsas, one of them recalled, lifted his arm feebly and tried to crawl out of the blazing aircraft. Then the bombs went off, pulverizing Dritsas and the Baltimore.

On 24 October Flying Officer Nikolaos Koskinas took off to bomb any enemy shipping caught off the southern coast of Crete, or failing that, unload the bombs on the German positions on Gavdos island. The only thing he found even vaguely resembling a hostile target were a couple of fishing boats at Gavdos that supplied the German garrison. Koskinas had just let his bombs go at low level when a barrage of flak hit his Baltimore and it had to ditch. The bomb-aimer and New Zealand wireless operator sank with the capsized bomber, while Koskinas managed to get the dinghy out and pull his wounded navigator-observer, Flying Officer Panos Tsirikoglou, into the dinghy with him.

The current dragged the dinghy south into the open sea, so Koskinas decided to swim to Gavdos, about three miles away, to seek help. He had swum about a mile when a German boat picked up both airmen. They were taken in stages to Chania, Athens and Thessaloniki. Koskinas made the gruelling trip barefoot, as he had shed his flying boots while exiting the downed plane. In Thessaloniki he finally got a pair of shoes and some food. He and Tsirikoglou were then put on a train to Stalag Luft I in Germany. The slow trip took two weeks, interrupted by bombing alerts and the activities of Tito’s partisans in Yugoslavia.

Stratis, the 13 Mira CO, was well-liked by his men, even the left-wing faction that still haunted the squadron. But according to Kartalamakis, the 201 Wing command never forgave Stratis for his near-insubordination in refusing to waste his crews in what he considered would be suicide missions against the lethal German flak batteries in Crete. One day Nasopoulos, now a flight lieutenant and the squadron’s second-in-command, was called to Alexandria where a couple of senior RAF officers told him crisply that Stratis was being relieved of command and that he, Nasopoulos, was being recommended to replace him. Nasopoulos flat out refused and went grimly back to base to tell his CO what had happened.

Stratis didn’t appear to be surprised. In fact, he was already thinking of asking for a transfer from the squadron. Nasopoulos suspected the British were making Stratis’s life difficult. In retrospect, the fault appears to have lain with the heavily left-leaning clique in the Greek Air Ministry-in-exile in Cairo, where ‘power-mad’ Fanis Metaxas, the instigator of the Rhodesia mutiny, held the key to personnel promotions and transfers. Stratis’s superiors in Cairo told him with straight faces that he was being replaced for not being ‘democratic enough’ with his men.

‘I belong to my country,’ Stratis retorted, ‘and to no political party. As long as I wear this uniform I will not allow anyone to tell me what my politics must be, or demand to know what I believe.’

Soon 13 Mira found itself in the hands of Squadron Leader Panayotis Papapanayotou, a highly regarded and respected officer. It’s a moot point whether Stratis was the victim of British resentment of his independence or leftwing fear that he was becoming too popular in the squadron. Kartalamakis, our sole source for the above exchange, leans towards the latter theory.

None of this, of course, made it any easier over Crete, whose German defences were becoming notorious. The sheer strength of flak on the island made any bombing mission an ordeal. No matter how fast and low a Baltimore could come in over the danger zone of Souda Bay, the blue Cretan sky would turn into a grey-black hell of flak bursts in a matter of seconds. The shock waves from the explosions buffeted the planes about violently, with serious risk of mid-air collision. The tension during the bombing run and the seconds of level flight needed to take the aiming-point photo was such that Pilot Officer George Tsitsoglou, for one, would whoop and sing uncontrollably during the pull-out. As Tsitsoglou would have been the first to admit, however, much of the bombing was wildly off. And it was a rare Baltimore that turned for home without some damage.

Even then the danger wasn’t over. Luftwaffe fighters usually prowled the coast for the unwary straggler, but the Baltimores almost always shook them off by diving for speed and hugging the waves. One of those that didn’t dive, though, was that of Tsitsoglou, who after one raid was seized with battle fever and decided to test his mettle against the Luftwaffe. His dorsal gunner soon saw a pursuer. ‘Tally-ho!’

‘Where’s the enemy?’ Tsitsoglou said.

‘Enemy aircraft behind and upper port,’ the gunner said.

‘Stand by for attack.’

The adversary was an Arado Ar240 heavy fighter, which Tsitsoglou turned to meet head on, shoving the throttles to maximum power. The Baltimore’s nose guns blazed first, throwing the Arado off and possibly unnerving its pilot who promptly fled. Shaking and sweat-soaked with the excitement of the encounter, Tsitsoglou barrelled home at top speed, forgetting to throttle back, at 12,000 feet. Much later, he felt more than a tinge of regret at unnecessarily endangering the safety of his crew. ‘I still wonder if that really happened or if it was some nightmare brought on by the hell of the flak over Souda,’ he wrote.

The two Greek Hurricane squadrons also shared the hazardous Crete operations. Towards midnight on 13 November Flight Sergeant George Mademlis of 336 Mira went to bed after being briefed for the following morning’s mission: to attack a concentration of enemy shipping in Mirabello Bay in north-eastern Crete. He slept fitfully if at all, very conscious of the adjacent empty bed that belonged to his squadron mate who had disappeared over Crete the previous day. Early in the morning Mademlis joined three other bleary-eyed pilots for hot tea while the ground crews ran up the Merlins.

It took the four Hurricanes an hour to cross the miles of sea to Crete, flying at no more than thirty feet above the waves. On the south coast the formation spotted a German military column and dived to rake it with cannon fire. At the same time a flak gun opened up on a hillside. They were entering the notorious Ierapetra plain that narrows at its northern end where it enters the hills. This narrow point formed a funnel into which German flak could pour murderous fire. Flight Sergeant Dimitrios Sarsonis’s plane took two hits, caught fire and dived straight into a farmhouse; Sarsonis was flung out on impact, aflame from head to toe. The crash also killed a fourteen-year-old Cretan girl visiting her newly married sister in the house. Flying Officer Constantine Psilolignos’s plane was also hit but stayed in the air. Mademlis flew in close to take a look and saw Psilolignos slumped over the controls, dead. The unfortunate pilot’s plane flew on a while and crashed in the hills.

Flak shrapnel holes appeared in both of Mademlis’s wings. Karydis, the mission leader and now a flying officer, led the way to the designated target and the two remaining Hurricanes found themselves over the brilliant blue of Mirabello Bay — and flak that the pre-mission briefing had said wouldn’t be there. Their attack was successful and they were turning to go when a flak shell exploded in Mademlis’s oil tank. He radioed Karydis that he was going to force-land, to hear the mission leader say that he, too, was hit and going to do the same. Once on the ground, Mademlis limped to hide in a small country church, wounded in the leg. The following morning a German patrol flushed him out at gunpoint. Karydis managed to reach the south coast of Crete, where he ditched in the middle of a marine minefield and was captured in short order.

Crowds of Cretans attended the funeral of Sarsonis and Psilolignos, the two dead Greek airmen, at Ierapetra cemetery. The Germans buried them with full military honours. The local German commander delivered a remarkable graveside eulogy, indicating that the sense of honour in the German military had by no means been extinguished. The officer said:

Yesterday, our uniforms and flags divided us. Today, though, we are called upon to honour the soldiers who fell for their country . . . These soldiers, however, were enviably favoured: they fell on the soil of their beloved country, a favour that all fallen soldiers would wish for, especially our own soldiers on the Eastern front, where the bodies of our dead are exposed to the cold and inhospitable snow.

Four losses by 336 Mira in a single mission was the most concentrated blow the Greek air force suffered while based in North Africa. Crete was turning out to be a Russian roulette. Souda Bay had earned notoriety as a suicide target. An Australian squadron had recently been devastated over it. The Allied strategy was to use the Souda raids to disorient the Germans and confuse them as to the intentions of the Allies in the eastern Mediterranean. Costly, yes, but the other side of the coin was that Greek pilots browned off by constant convoy duty often sought the Crete operations for some excitement, however dangerous.

Spyros Diamantopoulos, the 336 Mira CO who was shot down and captured, had no regrets about Crete. Convoy duty, he wrote long afterwards, was fatiguing and boring to the point of neurosis. But the Crete operations ‘were a kind of escape, something different, something exciting, a chance to fire our machine guns at the enemy . . . the Crete operations gave the exiled Greek air force a chance to prove itself the equal of the mighty RAF.’

Deepening the gloom in 336 Mira was the creeping realization that the Greeks’ Hurricanes were ageing, slow and vulnerable to the bristling defences in the Ierapetra plain and Souda Bay. Requests to the RAF for newer machines were routinely turned down with Air Vice-Marshal Park’s excuse that convoy escorts didn’t need anything better. The pilots may be excused for not seeing it that way. In both mirai they had to suffer the regular humiliation of being unable to pursue the Luftwaffe’s faster Junkers Ju88 and Heinkel He111 reconnaissance bombers. And nothing, oddly enough, was said about the Hurricanes’ Crete missions. Soon, though, the tables would turn.