For more than two years the Germans had been turning Crete into a near-impregnable Mediterranean fortress. Operating out of Cretan bases, the Luftwaffe reconnaissance bombers of I./KG1, II./LG1 and Aufklaerungsgruppe 123 were a constant menace to Allied warships and convoys negotiating ‘Bomb Alley’. Meanwhile, word had been seeping out from Crete about the atrocities the Germans were committing on the population in reprisal for the islanders’ fierce guerrilla resistance. Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas, the RAF C-in-C Middle East, thinking in terms of morale, thought it might be a good idea for the Greek squadrons to take part in aerial attacks on Crete’s German strongholds. In preparation, Douglas and King George II visited 335 and 336 Mirai to gauge their resolve.

There wouldn’t be room, though, for all the Greeks. As well as 335 and 336 Mirai, at least five other RAF squadrons would also be having a go at Crete, including 94 Squadron with mixed British and Serb crews, 213 Squadron with Spitfires and 252 Squadron with deadly swift ground-attack Bristol Beaufighters. So there was no choice for the Greeks but to draw lots for who would go. The lucky ones whose names were called ‘jumped up and shouted out loud like children’. The rest were sunk in gloom. A few of the latter offered to buy their way onto the mission, but no one was selling.

Morale among the Greek flyers was probably never so high as in the early morning of 23 July 1943, when on airfields from Alexandria to Tobruk they slammed their throttles forward to finally exact some revenge for the brutal occupation of their homeland. Pilot Officer Eleftherios Athanasakis of 336 Mira lost a wing tank on take-off but was damned if he was going to miss out on the big day. His wingman, Pilot Officer Constantine Kokkas, drew alongside and signalled to Athanasakis to turn back, but no way!

Leading the formation of 120 attacking aircraft in a Beaufighter was Wing Commander Max Aitken, the son of Britain’s minister for aircraft production and media baron, Lord Beaverbrook. In the first stage, Aitken was to knock out the German radar station at Ierapetra on the south coast of Crete. The formation headed swiftly in at low level. Aitken, Athanasakis and Kokkas were in the wave that bombed the Ierapetra radar. Flying on, they found themselves over the Aghios Nikolaos plain in eastern Crete, where Athanasakis, having flown on only one wing tank, ran out of fuel and radioed that he would have to force-land.

Kokkas later recalled:

The flak was ferocious but we gave as good as we got. I saw a German flag fluttering in a building on my right and sent a machine gun burst into it. We were almost touching the windmills and the milk-white houses, while the Cretans were throwing their hats into the air and dancing with joy, waving their hands all the time.

The Cretans were overjoyed to see the blue and white spinners on the Hurricanes. Near Heraklion the Greek pilots caught some Germans bathing at a beach and dyed the sea with German blood.

The sky over Heraklion was black with flak bursts. A shell hit Pilot Officer Sotirios Skatzikas, the brother of Sarandis Skatzikas, covering his Hurricane in oil. Kokkas, alongside, saw Skatzikas make a thumbs-down motion and that’s the last he saw of him. When the formation turned to go, thirty planes had been either shot down or forced to land. Athanasakis paid the ultimate price for his valour, as he may well have expected to. After belly-landing he tried to elude a German a patrol chasing him; when he saw he was cornered he drew his pistol to defend himself and was shot dead.

Skatzikas survived his crash but was captured, ending up in Stalag Luft III at Sagan. When the March 1944 Great Escape was organized he eagerly joined, and was one of the first to break out of the famous tunnel. Fifty recaptured Allied airmen were executed by the Gestapo, and Skatzikas was one of them. He may have remembered in his last moments that the date — 25 March — was Greece’s independence day.

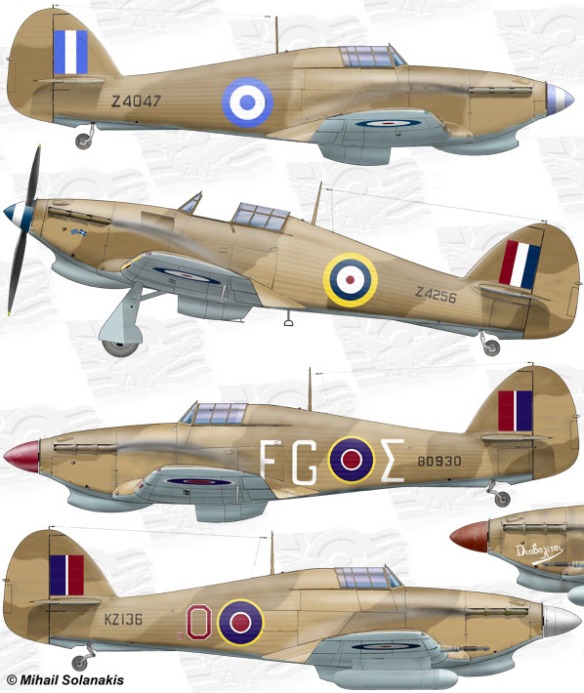

The first Crete operation cost the Greeks four pilots. The fact that they were lost in defence of their homeland fired the others to fresh resolve. In November they got a second chance to strike a blow for Crete in another joint raid with the RAF. This was to support amphibious landings on the Dodecanese islands by shooting up German targets on the Cretan coast. Again, the crews were chosen by lot. Diamantopoulos, the CO of 336 Mira, personally picked the names out of his own hat. The ground crews got to work polishing the Hurricanes and writing encouraging messages to the Cretans on the jettisonable wing tanks.

Before dawn the Greek Hurricanes roared off with their canopies open, hugging the dark waves, the sea spray stinging the pilots’ faces. They sped over Gavdos, the small island to the south of Crete, and into the mountains. Again, the Cretan peasants, glimpsing the blue and white spinners, erupted in joy. ‘Midshipman’ Stavropoulos, the incredulous hoots of his messmates still ringing in his ears after his inadvertent five-day naval career, had the satisfaction of shooting up German fuel tanks and weapons dumps. Diamantopoulos, ignoring intense machine-gun fire from the surrounding heights as his orders were to make one pass only, caught sight of a fuel tanker on fire and on its way to Heraklion aerodrome. Intent on hitting it, and constrained by the defile he was flying through, he exposed his starboard side to a flak burst, which smashed into his engine and blinded him with flying glass from his windscreen. Already perilously low, the Hurricane dropped a wing and crash-landed.

Diamantopoulos, seriously injured, was picked up by a German patrol. The Germans didn’t think he would live, so they didn’t bother to give him emergency medical treatment. It would be ‘a waste of medicine’, the German doctor told the officer who found him. The officer, a major, turned out to be a rather kinder soul, however, and that same night put Diamantopoulos on a transport to Athens. The Ju52 had barely started its engines at Heraklion when a flight of Beaufighters appeared above Heraklion, plunging the city and aerodrome into blackness. It occurred to Diamantopoulos that it would be ironic in the extreme if an RAF rocket killed him while the Germans were trying to save his life.

His sense of unreality increased when the Ju52 landed at Tatoi, the site of the former Icarus School, which had been turned into a German military hospital. When he was placed in the ward that had been his pre-war dormitory as a cadet, he was so moved he couldn’t speak, until the curious German airmen in adjacent beds started a conversation by asking him what kind of planes the Greeks were flying in the Middle East. He was later moved to a civilian hospital north of Athens where he found some survivors of the Greek submarine Katsonis, which had been sunk about that time, and a few British prisoners captured in the Dodecanese landings. All were later piled onto a train for the long trip to POW camps in Germany.

Flak had also hit Stavropoulos as he was making his third pass at 150 feet. He looked nervously at his port wing, which was full of holes, hoping the fuel tank wasn’t hit. It wasn’t, so with his mission completed, he turned for home. Strict radio silence had been imposed on all returning pilots up to fifty miles from the Cretan coast. When that point was passed, and Stavropoulos’s Hurricane was at 1,000 feet, he called up his wingman, Soufrilas, who he had last seen pulling up out of a ravine. By way of reply, Soufrilas came up by his side. Then Stavropoulos thought he was going mad.

Peering ahead over his gunsight, he saw two eyes looking back at him. The eyes came nearer, followed by two tiny legs. A weird fear crept over him. What was this monstrous hallucination? The eyes became a tiny face that resembled a piglet with a moustache and a great long tail. It took some moments for him to realize that it was a giant brown desert rat that somehow had got into his plane at the base and had been his fellow aircrew-member on a combat mission! The engine noise and gun bursts had terrified the poor creature. Stavropoulos felt sorry for it, reflecting that the rodent could have been a mascot that saved his life. Back on the ground, he took the rat back to its desert home.

The loss of Diamantopoulos cast a pall over 336 Mira. Sarandis Skatzikas, the brother of prisoner-of-war Sotirios now in Stalag Luft III, and meanwhile promoted to flight lieutenant, was given temporary command. The following day a flight of 336 Mira was again ordered to shoot up the important road between Heraklion and Chania on the north coast of Crete. The flight took off from Tobruk in depressed spirits. Skliris was the last in line astern as the flight swept into Crete. In an unguarded moment, while he stooped to switch fuel tanks, he hit a couple of trees, damaging the propeller. There was no alternative but to turn around and ditch, but before doing so he thought he’d get in a couple of hits at the enemy flak, which he did. In the event, Skliris’s battered propeller didn’t give up and eventually got him back. Each of the three propeller blades was found to be missing about six inches of its length.

By the middle of 1943 the Allies had acquired complete effective radar coverage of the North African coast. The Luftwaffe, naturally, tried to counter this by low-level under-the-radar raids. In response to that, the RAF organized wave-top-height sweeps in approximate three-hour shifts covering the daylight hours, starting out from airfields from Beirut to Benghazi. Each sweep would cover about 150 miles. It was tedious work and dangerous as well, as the very low height left no room for baling out or ditching safely in case of emergency.

Both 335 and 336 Mirai had their share of the sweeps, which they had to do over and above their normal convoy escort duties. A typical escort mission would involve an hour or more of circling at 2,000 feet above a convoy, and that was it. Thousands of flying hours were racked up this way, and naturally most Greek pilots chafed under the boredom of it all. The attacks on Crete were a tantalizing taste of what they could accomplish in real combat. Death by drowning after an engine failure over the sea, or in a fireball while releasing some pent-up high spirits, was not the way most men of the RHAF wanted to fall in battle. Kartalamakis, for one, was beset by mental images of ‘Death greedily prowling the Mediterranean, brandishing his scythe to cut down the first unlucky, absent-minded or novice pilot in the momentary absence of his protecting Saint.’

Pilot Officer George Xanthakos’s Hurricane of 336 Mira caught fire over a convoy eighty miles north of the coast. As he parachuted into the sea a rescue amphibian flew to the scene, but as it touched down a great swell overturned it and it began to sink. The five-man flying boat crew now joined Xanthakos bobbing in the rough sea, while back at base, his squadron mates waited anxiously by the telephone. Towards morning it rang with the news that while a rescue ship had picked up the five British airmen, it had found no sign of Xanthakos. Grimly, as daylight was approaching, the squadron got ready for another escort mission.

For the next two days, when they had time, the Hurricanes swooped and dived over the spot where Xanthakos had last been seen. Worst of all was the thought that their squadron mate may well have been waving frantically at them, but — as happened all too often — all that could be seen from the cockpit were the endless, undulating grey and white flecks. A terse order arrived from 219 Wing headquarters that all searches be stopped and Pilot Officer Xanthakos be considered lost. The RAF allowed a maximum seventy-two hours for searches at sea. A week later a camel with a donkey tied behind it lumbered slowly out of the desert towards 336 Mira’s base. A few pilots lounging outside the ops room idly watched them approach in the company of a band of jellaba-clad locals. Hatzilakos, now a pilot officer, saw a hand shoot up from among them. It was Xanthakos, weak, and suffering from burns, whom the Bedouin had picked up on the coast.

He had floundered in the heavy seas in his Mae West for three days, seeing all too clearly the planes sent out to look for him. He was tortured by hunger and thirst, sunburn by day and cold by night, and salt water stinging his burns. Eventually, the waves cast him up on the shore. For two days the Bedouin nursed him in their huts until he could walk. He was driven to a hospital in Alexandria, where he recovered enough to be back flying with 336 Mira above the same treacherous seas. When asked about how he felt, he would laugh it off, saying that the sea had made its peace with him now.

Re-equipment, meanwhile, was in progress at 13 Light Bomber Mira, based at Gabut. Its ageing and increasingly cantankerous Bristol Blenheim IVs and Vs had reached the end of the line. One of them had just been serviced at a maintenance unit at Tobruk and Flying Officer Nikolaos Hartokolis was deputed to fly it back to the base with Sergeant Anastasios Bales, a fitter, as his passenger.

The Blenheim’s engines had been problematic. Though the RAF maintenance men insisted they were all right after the service, an initial engine run-up had found the twin Bristol Mercury radials unsynchronized. Hartokolis had been warned about that, but seems to have made light of the problem as he set out to pick up the aircraft. Shortly afterwards, witnesses heard the sound of a Blenheim taking off — followed by the unmistakable discordant sound of engines out of synch, and an explosion. Men ran out to see the Blenheim crumpled on the ground, awash in blazing kerosene and its ammunition belts going off. The sick odour of burning flesh wafted over the sand.

The fire eventually was brought under control to reveal the blackened bodies of Hartokolis and Bales still strapped into their seats. Then three more bodies were brought out — those of RAF men who had, against regulations, gone along on the proving flight! Officially, the crash was caused by a faulty control cable connection to the elevators, pushing the plane down when it should have gone up. But what seems equally likely, according to an engineer of 13 Mira, is that one engine failed on take-off, causing a wing stall. When the pilot pitched the nose up to deal with the wing stall, the weight of the three unauthorized passengers could have kept the tail down, causing a full stall.

It was just after that tragic loss that 13 Mira received its shiny new Martin A20 Baltimore twin-engined light bombers supplied by the RAF and paid for by wealthy Greeks in America. Faster, tougher and much more powerful than the Blenheim, the Baltimore bristled with ten guns in the nose, dorsal turret and belly, and could carry nearly 2,000 pounds of bombs. The new attack bombers had their baptism of fire on 14 October 1943 with orders to hit the German fuel dumps on Gavdos, the small island south of Crete. A three-Baltimore formation led by Flight Lieutenant Stratis, the CO, roared in low over Gavdos under the radar. Stratis could see farm chickens scattering in panic. Just as he and his fellow-pilots, Angelidis and Flying Officer George Pattas, were turning away after bombing, a volcano of flak erupted around them. Pattas’s plane, on the inside of the curve, took the most punishment. Miraculously, the crew were unhurt and nothing vital was hit. All three returned safely to base. The Baltimore was starting out with a good omen.