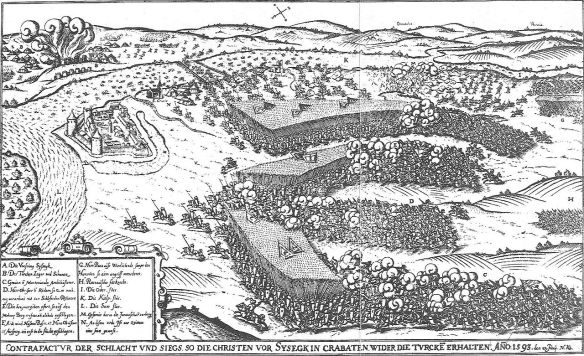

“DIE CHRISTEN VOR SYSEGK IN CRABATEN Anno 1593”

(“The Christians Before Sisak in Croatia A.D. 1593”)

(Hieronymus Oertel, Nuremberg 1665)

Europe 1600.

Habsburg–Ottoman Relations after 1606

More immediately, the Peace of Vienna cleared the way for Matthias to end the debilitating conflict with the sultan by concluding the Treaty of Zsitva Török on 11 November 1606. This fell short of a permanent peace that neither side was willing to accept. Nonetheless, both the sultan and the emperor were obliged to recognize each other as equals, and the humiliating annual tribute of 30,000 florins paid by the Habsburgs since 1547 was to be replaced by a final ‘free gift’ of 200,000. The sultan retained Kanizsa and Erlau, but had to permit the emperor to construct new fortresses opposite them. The arrangement was to last twenty years, during which cross-border raiding would be tolerated, provided no regular troops were involved.

It was the Habsburgs’ good fortune that the Ottomans were unable to renew the war after 1606. The sultan managed to suppress his own revolts by 1608, but was forced to accept peace with Persia by 1618, confirming the loss of Azerbaijan and Georgia. The Persians exploited ongoing unrest within the Ottoman Empire to renew the war in 1623, capturing Baghdad and slaughtering all the Sunni inhabitants who failed to escape. The loss of Iraq triggered convulsions throughout the Ottoman Empire, including major revolts in Syria and Yemen which disrupted revenue collection and the routes to the holy sites. The sultan meanwhile lost control over the Crimean Tartars who provoked an undeclared war with Poland that lasted, intermittently, until 1621. Faced with these problems, he was only too happy to confirm Zsitva Török in 1615, accepting minor boundary adjustments that improved Habsburg defences around the Gran salient. The Bohemian Revolt coincided with Persia’s victory, and the sultan went out of his way to conciliate the emperor, even offering him a few thousand Bulgarian or Albanian auxiliaries in the summer of 1618. Though these were politely declined, Osman II sent a special ambassador to congratulate Ferdinand II on his election as emperor the following year. Ottoman benevolence was doubly welcome, because the Reichstag did not renew the last frontier subsidy when this expired in 1615. The Bohemian crisis forced the Austrians to denude the frontier of troops, raising 6,000 cavalry from Croatia and Hungary in 1619. Around 4,000 frontier troops served with the imperial army thereafter until 1624, largely under the command of Giovanni Isolano, a Cypriot with property in Croatia who established his reputation during the Long Turkish War. There was little money left to pay the remaining garrisons on the frontier, prompting mutinies in the Slovenian and Croatian sectors in July 1623. Though the Transylvanians sided with the Bohemians, the sultan refrained from exploiting the opportunity, and without his help their intervention soon collapsed.

With their respective governments distracted by war elsewhere, cross-border relations devolved to the Hungarian palatine and the Ottoman pasha in Buda. The former position was held by Miklós Esterházy between 1625 and 1645. He fostered the humanist vision of Hungary as Christendom’s bulwark and encouraged the Magyar nobility to place their faith in the Habsburgs as the best guarantors for immediate defence and the eventual recovery of the lands lost to the Turks. His negotiations at Szöny with the pasha of Buda in 1627 secured a fifteen-year extension to Zsitva Török, buying more time for the emperor to confront his Christian enemies. The Ottomans did exploit the Mantuan War to plunder fourteen villages in the upper Mur valley in 1631, but they rejected a Venetian suggestion to extend their attacks. Though Sultan Murad IV finally restored order in the Ottoman Empire around 1632, suppressing the provincial revolts, he preferred to turn against the Persians, hoping to defeat them while the Habsburgs were preoccupied in Germany. Ottoman armies recovered Azerbaijan, Georgia and Iraq, retaking Baghdad in 1638 and forcing Persia to accept these losses the following year.

The relative quiet allowed the emperor to draw more soldiers from the frontier as the war in Germany intensified from 1625. An initial Croat regiment was raised that year, followed by two more by 1630. Swedish intervention that year prompted a dramatic expansion to fourteen regiments by 1633, as well as 1,500 Kapelletten, or light cavalry recruited in Friuli and Dalmatia. The number of Croat regiments peaked at 25 in 1636, falling to 10 three years later and 6 by the end of the war. Constant recruiting nonetheless depleted the frontier garrisons, leaving only 15,000 effectives by 1641, around 7,000 below official establishment. This was still a large force, equivalent to the numbers deployed in a major battle during the latter stages of the war. It represented a major commitment in men, money and materials at a time when the emperor was increasingly hard-pressed, a factor that has been mostly overlooked when assessing the imperial performance during the conflict.

The continued military presence along the frontier indicated how deeply the Habsburgs still feared the Ottoman menace. Their concerns seemed justified when the Turks followed their peace with Persia in 1639 by launching major raids intended to consolidate their hold on Kanisza. Things might have got much worse if the Persian war had not resumed, prompting the sultan to renew Zsitva Török again in 1642, this time for twenty years. The sultan’s problems weakened his hold over Transylvania, which had remained nominally under his suzerainty after 1606. As Transylvania grew more independent, its prince felt emboldened to intervene again in the Thirty Years War in 1644–5. Thus, while Ottoman weakness kept the sultan out of the war, it paradoxically enabled Transylvania to join it. Still, it was always preferable to face the Transylvanians rather than the more powerful Ottomans. Fears that the pasha of Buda would back the prince with infantry and artillery never materialized, which rendered Transylvanian intervention in the war largely ineffective. Just as Transylvania made peace, the sultan became preoccupied with a new conflict against Venice that dragged on until 1669. Demobilization following the Peace of Westphalia obliged the emperor to withdraw his troops from the Empire, and he moved them into Hungary where they deterred further Ottoman raids until 1655. It was not until the late 1650s that the Ottomans were strong enough to pose an active threat and their attempts to reassert influence over Transylvania prompted another war with the emperor after 1662 that ended with a further renewal of Zsitva Török in modified form two years later. The stalemate only broke with the failure of the Ottoman siege of Vienna that opened the Great Turkish War of 1683–99. International assistance enabled the Habsburgs to drive the Turks from Hungary, which was converted to an hereditary kingdom in 1687, followed by the annexation of Transylvania four years later. The victory transformed Austria into a great power in its own right, lessening the significance of the Holy Roman title.

These glories would have appeared an impossible dream to the Habsburgs surveying the wreckage of Rudolf’s policies by 1606. The frontier had been weakened by the loss of two of its greatest fortresses, the dynasty had lost ground in Hungarian politics, and all influence in Transylvania had been extinguished. However, the repercussions went well beyond the Habsburgs’ eastern kingdom to shake the very foundations of their monarchy. Despite receiving over 55 million fl. in subsidies and taxes during the war, Rudolf’s debts had climbed to 12 million. Key sources of revenue, such as the Hungarian copper mines, had been pawned to raise further loans. The border troops were already owed 1 million fl. in back pay by 1601, while the field army had arrears of twice this by the end of the war. Six thousand soldiers loitered in Vienna demanding at least a million florins to disperse. Habsburg inability to keep order in their own capital underlined their failure. Disappointment and disillusionment spread to the Empire where the princes found it hard to believe that their money had not bought victory. The imperial treasurer, Geizkofler, was formally charged with embezzling half a million florins, and though he was acquitted in 1617, many princes failed to pay their share of the last border subsidy, voted in 1613, which was still 5.28 million fl. in arrears by 1619.