Building a Viking-Ship

The earliest Viking vessels were copied from Roman or Celtic designs and powered by oars instead of the usual paddles. Like all ships of the time they were slow and prone to capsizing in rough seas, appropriate for short trips that hugged the shore. Sometime in the eighth century, however, the Vikings invented the keel. This simple addition is among the greatest of nautical breakthroughs. Not only did it stabilize the ship, making it ocean-worthy, but it provided a base to anchor the mast. A massive sail, some as large as eight hundred square feet, could now be added as the major source of propulsion. The impact was immediate and stunning. In a time when few Europeans ventured far from land, the Vikings criss-crossed the Atlantic with cargoes of timber, animals, and food, covering distances of nearly four thousand miles.

To aid steering on these long voyages, the Vikings used a special oar which they called a Styra bord, or ‘steering board’. In deference to the dominant hand of most sa ilors it was placed on the right side of the ship near the stern to make the ship easier to control. From this we get the nautical term ‘starboard’, which refers to the right side of a vessel. The opposite term also owes its existence – albeit more indirectly – to the Vikings. When ships reached the port they would usually be docked on the left side to avoid damage to the steering oar. Over time, ‘port’ was used as a shorthand for ‘left’.

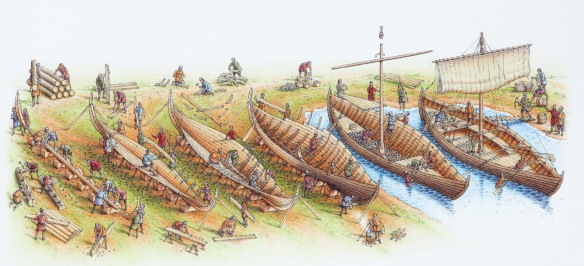

A number of different ships were developed – cargo vessels, ferries, and fishing boats – but the warships, or longships, in particular were a brilliant combination of strength, flexibility, and speed. Built to glide over the surface of the water, the longships could be made from local materials, without the specialized labor needed for Mediterranean vessels. The ships of the south were both costly and clunky, held together with multiple rivets and braces, and several decks. The Viking ships, by contrast, were clinker-built with overlapping planks of oak – always green instead of seasoned for greater flexibility – which allowed them to bend with the waves.

Viking ships were mostly undecked, unless made to stow cargo, which made the long Atlantic crossing a brutal affair. During rough seas, the waves would frequently break over the sides, and there was little protection against the lashing rain or sleet other than a simple tent pitched on the deck.

But what they lacked in comforts, they more than made up for with lethal simplicity. Viking longships lacked the keels of the larger ocean-crossing ships, and their relatively shallow drafts allowed them to be beached virtually anywhere instead of just the deep-water ports required by other vessels. This made it possible for a longship to navigate up rivers, and some were light enough to be carried between river systems.

The Viking poets called the longships ‘steeds of the waves’, but they were more like prowling wolves. The hapless victims of Viking attacks took to calling the northerners ‘sea-wolves ‘, after the predators that roamed the darkness outside of human habitation. The longships could accommodate up to a hundred men, but could be handled on the open sea by as few as fifteen. They were agile enough to slip past coastal defenses, roomy enough to store weeks of loot, sturdy enough to cross the stormy Atlantic, and light enough to be dragged between rivers.

But the most frightening thing about them was their speed. They could average up to four knots and reach eight to ten if the winds or currents were with them. This ensured that the element of surprise would nearly always be with the Vikings. A fleet in Scandinavia could cover the nine hundred miles to the mouth of the Seine in three weeks, an average of over forty miles per day. Under oar they were nearly as fast. One Viking fleet rowed up the hundred and fifty miles of the Seine – against the current and fending off two Frankish attacks – to reach Paris in three days. The medieval armies they faced, assuming they had access to a good Roman roads, could only average between twelve and fifteen miles per day. Even elite cavalry forces pushing hard could only manage twenty.

It was this speed – the ability to move up to five times as fast as their enemies – that made Viking attacks so lethal. With shallow draughts that could pass under bridges or up shallow rivers, fierce dragon prows, and brightly painted shields fitted onto the sides that glittered like scales, they must have been psychologically unnerving. In a single lightning attack, they could hit several towns and disappear before their opponents could even get an army into the field. Nor was there any hope for the victims of challenging Viking supremacy at sea. Between 800 and 1100 most major naval battles fought in the North Atlantic involved Vikings fighting each other.

As the ninth century dawned, all the pieces of the Viking Age were in place. The Scandinavians had an advantage at sea that was impossible to defend against, knowledge of the major trade routes, and an unsuspecting world in full view. The only thing that remained was to select a suitable target.

#

Charlemagne’s defenses, particularly the fortified bridges and army, were still formidable enough to blunt a large attack, but there were ominous signs that the situation would soon change. A Frankish bishop traveling through Frisia found help from ‘certain northmen’ who knew the routes up the rivers that flowed toward the sea. The Vikings were clearly aware of both harbors and sea routes, and the empire lacked a fleet with which it could defend itself.

The Franks, however, seemed oblivious to the danger. Life was more prosperous than it had been in many generations, and they were enjoying the benefits of imperial rule. The archbishop of Sens in northern France, confident in the protection of the emperor, had gone so far as to demolish the walls of his city to rebuild his church. The towns on the coast were equally vulnerable. A lively wine trade had developed along the Seine between Paris and the sea, and the coast of Frisia was dotted with ports. Thanks to the Frank’s access to high quality silver – a commodity largely absent in Scandinavia – coins had replaced bartering and imperial markets were increasingly stockpiled with precious metals.

The only thing preventing a major attack was the confusion of Louis’ Viking enemies. The Danish peninsula had been in turmoil since the death of Godfred. A warrior named Harald Klak had seized power, but after a short reign had been expelled by the slain Godfred’s son Horik. Harald Klak appealed to Louis for help, slyly offering to convert to Christianity in exchange for aid. The emperor accepted, and in a sumptuous ceremony at the royal palace of Ingelheim, near Mainz, Harald and four hundred of his followers were dipped in the baptismal font. Louis the Pious stood in as Harald’s godfather.

It was a triumphal moment for several reasons. Louis was clearly not the soldier his father was, but here was an opportunity to neutralize the Danes for the foreseeable future. If Harald could be installed on the Danish throne, and then Christianize his subjects, it would pacify the northern border.

The first part of the plan worked seamlessly. Harald was given land in Frisia and tasked with defending it against marauding Vikings, while an expedition to restore his throne was gathered. With a Frankish army at his back, he was able to force his rival, Horik, to recognize him as ruler. He then invited Louis to send a missionary to aid in the conversion of the Danes. The emperor chose a Saxon preacher named Ansgar, who immediately built a church in Hedeby. At this point, however, Louis’ grand policy began to collapse.

The Danes weren’t particularly interested in Christianity, at least not as an exclusive religion. Nor it seems, were they interested in Harald Klak. After a year, he was again driven into exile by his adversary Horik, a stout pagan. To add insult to injury, Harald returned to his Frisian lands and took up piracy, spending his remaining years plundering his godfather’s property.

With the expulsion of Harald Klak, a dam seemed to break in the north, and raiders began to spill out over the Carolingian coast. Dorestad, the largest trading center in northern Europe and a main center of silver-minting, was sacked every year from 834 to 837. Horik sent an embassy to Louis claiming that he had nothing to do with the attacks on Dorestad, but did mention that he had apprehended and punished those responsible. The latter claim, at least, was probably true. Successful raiders were potential rivals, and Horik had no desire to repeat Harald Klak’s fate.

Individual Vikings out for plunder needed no invitations from the king to attack. The Frankish empire was clearly tottering. Louis’ tin-eared rule – exacerbated by an ill-thought out plan to include a son from his second marriage into the succession – resulted in a series of civil wars and his deposition at the hands of his remaining sons. Although he was restored to the throne the following year, his prestige never recovered.

The damage it did to his empire was immense. Not only were there lingering revolts – he spent the final years of his reign putting down insurrections – but the distractions allowed the Vikings to arrive in greater numbers. Multiple groups began to hit the coasts at the same time, burning villages, seizing booty, and carrying away the inhabitants, leaving only the old and sick behind.

In 836 Horik himself led a major raid on Antwerp, and when several of his warriors died in the assault, he had the nerve to demand weregild – compensation for his loss of soldiers. Louis responded by gathering a large army, and the Vikings melted away, but only as far as Frisia where they continued to raid. In 840, the emperor finally ordered the construction of his father’s North Sea fleet to challenge them, but died a few months later without accomplishing anything.

Instead of unifying against the common threat, Louis’ sons spent the next three years fighting for supremacy as the empire disintegrated around them. On occasion they even tried to use the Vikings to attack each other. The eldest sibling, Lothar, welcomed old Harald Klak into his court and rewarded him with land for raiding his brother’s territory. This turned out to be an exceptionally bad idea, as it gave the Vikings familiarity with and access to Frankish territory. Harald, and streams of like-minded Vikings, happily plundered their way across the northern coasts of the empire.

These attacks depended on speed, not overwhelming force. By the mid ninth century the typical Viking “army” consisted of a few ships with perhaps a hundred men. Some men would be left to guard the ships while the rest fanned out to plunder. In these early days they weren’t interested in prisoners, and would kill or burn anything that couldn’t be taken.

The small numbers were a vulnerability, but this was made up for by the speed of the attacks. Most Vikings were reluctant to travel far from the coasts of the sea or river systems, and generally avoided pitched battles. Their equipment was more often than not inferior to their Frankish opponents; Vikings caught in open country were usually overwhelmed. This was partially because they lacked the armor common in Europe at the time. Frankish chronicles referred to them as ‘naked’, and they had to scavenge helmets and weapons from the dead since several Frankish rulers sensibly forbade the sale of weapons to the Vikings on pain of death.

The one exception to this general inferiority were Viking swords. The original design was probably copied from an eighth century Frankish source, a blacksmith named Ulfberht whose name soon became a brand. The Vikings quickly learned to manufacture the blades themselves, and weapons bearing the inscription Ulfberht have been found all over Scandinavia. They were typically double edged, with a rounded point, made of multiple bars of iron twisted together. This pattern welding created a relatively strong and lightweight blade that could be reforged if broken. They were clearly among a warrior’s most prized possessions and were passed down as heirlooms and given names like “Odin’s Flame” and “Leg-Biter“.

Aside from their swords, the Viking’s main advantages lay in their sophisticated intelligence gathering and their terrifying adaptability. They had advance warning of most Frankish military maneuvers, and could respond quickly to take advantage of political changes. Most formidable of all, was their malleability. ‘Brotherhoods’ of dozens or even hundreds could combine into a larger army, and then re-dissolve into groups at will. This made it almost impossible to inflict a serious defeat on them, or even predict where to concentrate your defenses.

The Vikings were usually also more pragmatic than their opponents. They had no qualms about traveling through woods, used impromptu buildings like stone churches as forts, and dug concealed pits to disable pursuing cavalry. They attacked at night, and were willing – unlike the Frankish nobility – to get their hands dirty by digging quick trenches and earthworks. Most of all they could pick their prey and had exquisite timing. Earlier barbarians had avoided churches; the Vikings targeted them, usually during feast days when towns were full of wealthy potential hostages.

The Christian communities didn’t stand a chance. The monastery of Noirmoutier, on an island at the mouth of the Loire, was sacked every year from 819 to 836. It became an annual tradition for the monks to evacuate the island for the spring and summer, returning only after the raiding season had ended. Finally, in 836 they had enough and carrying the relics of their patron saint – and what was left of the treasury – they fled east in search of a safe haven. For the next three decades they were driven from one refuge to the next until they finally settled in Burgundy near the Swiss border, about as far from the Vikings and the sea as one could get.

A monk of Noirmoutier summed up the desperation in a plea for his fellow Christians to stop their infighting and defend themselves:

“The number of ships grows larger and larger, the great host of Northmen continually increases… they capture every city they pass through, and none can withstand them… There is hardly a single place, hardly a monastery which is respected, all the inhabitants take to flight and few and far between are those who dare to say: ‘Stay where you are, stay where you are, fight back, do battle for your country, for your children, for your family!’ In their paralysis, in the midst of their mutual rivalries, they buy back at the cost of tribute that which they should have defended, weapons in hand, and allow the Christian kingdom to founder.”

The monk’s advice went unheeded. By the time the Frankish civil war ended, Charlemagne’s empire had dissolved into three kingdoms, each with their vulnerabilities brutally exposed. The western Frankish kingdom became the basis of the kingdom of France, the eastern, Germany, and the third – a thin strip of land between them called Lotharingia – was absorbed by its neighbors.41 Viking raiding groups became larger and bolder. Instead of two or three ships traveling together, they were now arriving in fleets of ten or twelve. More ominously still, they began to change their tactics. In 845 they returned to the island of Noirmoutier, but this time, instead of the usual raid, they fortified the island and made it a winter quarters. The usual practice was to raid in the warmer months, and return home before the first snows fell. Now, however, they intended to stop wasting time in transit, and to be more systematic in the collection of loot.

Launching raids from their base, they could now penetrate further up rivers, putting more towns and even cities in range. Rouen, Nantes, and Hamburg were sacked, and Viking fleets plundered Burgundy. The next year they hit Utrecht and Antwerp, and went up the Rhine as far as Nijmegen. These raids all paled, however, before one that took place in 845 at the direction of the Danish king. He had not forgotten the Frankish support for his rival Harald Klak. Now Horik finally had his revenge.