It was inevitable that the time would come when the Germans, however belatedly, started to build tanks of their own. During the early months of 1918, stories began to trickle through from intelligence reports and the statements of captured prisoners that the Germans were building a monster tank, much larger and heavier than the British machines. In a very small way they had already used tanks in battle—a few Mark IVs captured in the Battle of Cambrai and manned by German crews. Now these tanks were withdrawn from the front line and used for training the newly formed German Panzer Corps.

The year had not started well for the Allies. The exhausting battles in Flanders had taken their toll so that the total number of French, British and Belgian divisions had been reduced from 178 at the beginning of 1917 to 164 by 1918. In addition, the strength of each British division had been reduced from thirteen to ten battalions, inevitably affecting their fighting efficiency. It was true that powerful reinforcements were expected from the United States, following her entry into the war during the previous April, but by March 1918 only four American divisions had arrived and these had not yet entered the front line. Apart from the general weariness of the troops, the Allies were hampered by internal friction among their generals and political leaders. In 1917 the British, who had taken the main offensive role, had a frontage of 100 miles as against 325 miles held by the French. After some argument, in which the French at first demanded that the British line be extended by a further 55 miles, Haig agreed to take on another 25 miles and no more, threatening to resign if overruled by the newly-formed Allied Supreme War Council. He had his way, so that by the early spring of 1918 the British with 58 divisions held 125 miles of the front while 99 French divisions took charge of 300 miles. The disparity was less than it seemed because half of the French line was of secondary importance. But the bickering between the two armies did little for morale, which was already at a low ebb.

The Germans on the other hand had reason for confidence. The collapse of Russia towards the end of 1917 had released divisions from the eastern front, to the point where the balance in the west was altered in their favour. Whereas at the beginning of 1917 the Germans were outnumbered nearly three to two by the Allies—129 divisions against 178—the situation a year later on the Western Front was 192 German divisions against 164 of the Allies. Realising the enormous potential of the United States once the build-up of her forces got really under way, Ludendorff decided to launch a major offensive in the hope of securing a quick victory and favourable peace terms. It was to begin on March 21st, initially against the 54-mile southern sector of the British line between the Oise and Sensée rivers.

By that time the British Tank Corps had been expanded to fourteen battalions with an establishment of 24,000 officers and men. The former lettered titles had been changed to numerical ones—A Battalion becoming the 1st Battalion and so on—but letters were used for companies which became A, B and C companies of each battalion. Two new tanks had been developed for use in the 1918 campaign. The heavy Mark V was again similar in shape to the Mark IV but with a much improved performance, reliability and manoeuvrability. A larger 150hp Ricardo engine gave it an increased speed of 4.6mph and new epicyclic gears designed by Wilson enabled it to be driven and steered by one man, a tremendous asset in battle since the rest of the crew could concentrate on firing the guns. The thickness of armour was increased from a maximum of 12mm on the Mark IV to 14mm, while the Hotchkiss replaced the Lewis machine guns. The worst feature of the new design was in placing the radiator inside the tank, for although it provided a more efficient cooling system than in previous models, it severely reduced ventilation for the crew.

The same problem was also found in the other new tank which came into service in 1918, the light Medium Mark A Whippet which had originally been designed by Tritton at the end of 1916. This was intended for exploiting a breach in the enemy’s line rather than crossing trenches and was armed only with light machine guns. It had a speed of over 8mph and a range of 80 miles compared with the Mark V’s 45 miles. The tracks did not go all round the hull but around a chassis on which the engine room and fighting turret were mounted, so that its shape was reminiscent of the original ‘Little Willie’. Its crew consisted of a commander and two men. While the role of the Mark V in battle was comparable to the heavy cavalry, the Whippet formed the light cavalry for skirmishing purposes.

The French had also developed tanks of their own. The heavy St Chamond (23 tons) and the medium Schneider (14 tons) had first been used in action in April and May 1917 but the results were disappointing. Both were virtually armoured cabins mounted on adaptations of the Holt tractor. Four hundred of each were built but they had poor cross country performance and limited fighting capacity. By 1918 the French had developed a light Renault tank of 6½ tons which was much more successful. It was relatively cheap to build and after its debut in battle later in the year, large numbers were ordered.

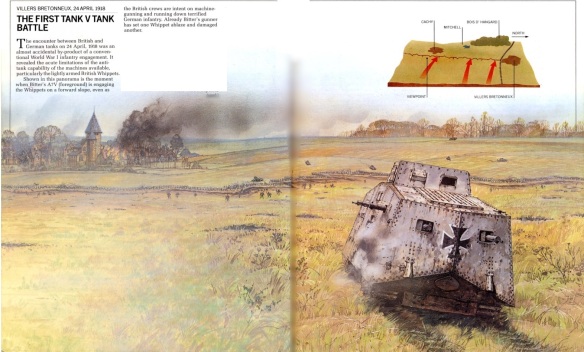

Just as the British High Command had underrated the machine gun, so the Germans underrated the tank. The real shock had come in the Battle of Cambrai when the Mark IV, its thicker armour impervious to bullets, showed how easily trench defences could be assaulted. The fact that there were flaws in the British plan which failed to take advantage of the breakthrough could not disguise the potential of this new form of warfare. The Daimler Motor Company had already designed a tank designated the A7V and now it was hurried into production. But in reality it was too late. There was not sufficient time for proper development work to be carried out. Only ten of these tanks were ready to take part in the March offensive. Later in the campaign, five more A7VS became available—making up the total of 15 built by the Germans before the war ended—and about 25 captured British tanks were also used. They were too few for the Panzer Corps to make any great impact in the battles of 1918.

Although clumsy and in many ways badly designed, the A7V was a monstrous vehicle that could strike terror in the hearts of the unprotected British infantry. It weighed nearly 40 tons and carried a crew of sixteen, sandwiched into a space 24ft long by 10½ft wide. Heavy 30mm armour plate that could withstand a direct frontal hit from field guns at long range extended right down over the tracks so that the tank looked like a huge tortoise. It had an impressive speed of up to 8mph and bristled with six machine guns and one 57mm gun, the equivalent of a 6pdr. Because of the underhanging tracks it had a very limited ground clearance and was unable to cross large trenches or shelled ground. The armour over the drivers’ cabin was too thin to provide much protection and numerous crevices in the plating made it highly susceptible to bullet splash. Its most interesting feature, not yet incorporated in British or French tanks, was the provision of sprung tracks to give a smoother ride on flat ground.

Tanks played little part in the opening stages of the great German offensive, for which new techniques had been devised. The artillery bombardment was started without previous ‘registration’ fire so that it came as a sudden, paralysing blow, increased by the use of a high proportion of gas shell. Having learned the value of a surprise attack, just as the British had at Cambrai, the German infantry began to move forwards almost immediately, followed by the second line reserves who were thus on hand when they were needed. Instead of advancing on an even front and waiting while centres of resistance were overcome, the German infantry had been trained in new infiltration tactics to follow along the line of least resistance. They were aided by a thick mist which covered the 54 mile battle front on the morning of March 21st. The front line defences of the British Third and Fifth Armies were overrun even before the defenders were aware of it. With 64 divisions taking part against 29 British infantry divisions and three cavalry divisions, the Germans advanced rapidly and by the end of the first day had breached the battle zone in several sectors. The British front was in danger of collapse.

Meanwhile the bulk of the British tank battalions, comprising at that time 324 Mark IVs and about fifty Whippets, had been distributed in three main groups some ten miles behind the front. As a defensive scheme in preparation for the expected German offensive, most of them were hidden in concealed positions, the idea being that they would emerge ‘like savage rabbits from their holes’ to ambush any German units penetrating the battle zone. In view of their slow speed and inability to move quickly to the areas where most needed, it was not a role particularly suited to tanks. The whole initial period of the battle became known to the Tank Corps, somewhat sarcastically, as ‘Savage Rabbits’.

During the days of crisis that followed, pockets of these tanks did invaluable work in preventing the British retreat from becoming a rout. The most critical moments came on March 26th when the Germans, having advanced nearly 20 miles on a front of about 40 miles, strenuously attempted to make the final breakthrough. It was on that day that the Whippets came into action for the first time, preventing the enemy from taking advantage of a four mile gap which had opened up in the Third Army’s defences at Serre, and it also marked a momentous decision by the Allies to appoint General Foch as Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Armies to co-ordinate the operations of the French and British forces. By nightfall, due in no small part to counter attacks by both light and heavy tanks, the immediate danger had passed. The Germans had made the greatest advances since the war had become deadlocked in trench fighting but could not keep up their supplies across the devastated ground. North of the Somme the front became stabilised by the reformed British defences and little further ground was lost. Southwards, the Germans advanced over the next two days until they were nearly at Villers-Bretonneux, only ten miles from Amiens. It was at Amiens, with its vitally important railway junction, that the British and French armies met and it was largely with the intention of breaking between them that the German offensive had been launched. But the British withdrawal in this area had been conducted largely to conform to the position taken by the French. Although the Germans had driven a wedge nearly forty miles deep in the British lines towards Amiens and taken about 80,000 prisoners, they had for the time being shot their bolt.

Between March 28th and April 18th the Germans switched their attack to other sectors of the front, first at Arras and then, when that failed, towards Hazebrouck in Flanders. Here, the British were forced to abandon the ground that had been won so dearly at Passchendaele the previous year but managed to check the German advance by withdrawing to a shorter line at Ypres.

On April 24th the Germans made a renewed effort in the south by a surprise attack on Villers-Bretonneux. For the first time in the war they decided to use tanks to spearhead the attack, bringing up twelve A7VS secretly to the front under cover of darkness. It was at Villers-Bretonneux, on high ground overlooking the Somme valley with the rooftops and cathedral spire of Amiens clearly visible beyond, that the first confrontation between tanks took place.

The German attack began early in the morning with an intensive bombardment of high explosive and gas shells. When this lifted at about 6am the troops in the British forward trenches prepared themselves for the infantry assault. But it was not the expected stormtroopers who came through the thick fog which persistently clung over the Somme country. Instead, there came the looming, fearsome shapes of German tanks, the noise of their approach having been drowned by the roar of shellfire. They created the same kind of havoc in the forward trenches as the British tanks had done at Cambrai. With no antitank weapons to combat these monsters, the British troops either ran or surrendered. In the words of the British Official History, ‘wherever tanks appeared the British line was broken’. A three mile gap was speedily opened for the oncoming stormtroopers. By the time the morning fog had lifted, the Germans had captured Villers-Bretonneux and the leading tank was already lumbering on towards the village of Cachy. The situation was desperate.

It so happened that lying up in the wood between Villers-Bretonneux and Cachy were three Mark IVs, appropriately enough the No. 1 Section of A Company of the 1st Tank Battalion, commanded by Captain J. C. Brown, MC. Two of these were female tanks, armed only with machine guns, but the third, under the command of Lieutenant F. Mitchell, was a male tank armed with 6pdrs. The section had been overwhelmed by the earlier gas shelling, which had disabled some of the crews, but the three tank commanders were given orders to proceed to the Cachy switch line and hold it at all costs. The story was described later by Lieutenant Mitchell.

“As the wood was still thick with gas we wore our masks. Whilst cranking up a third member of my crew collapsed and I had to leave him behind propped up against a tree trunk. A man was loaned to me by one of the females, bringing the crew, including myself, up to six instead of the normal eight. Both my first and second drivers had become casualties so the tank was driven by the third driver, whose only experience of driving was a fortnight’s course at Le Tréport (the base camp).”

As Mitchell had previously reconnoitred the ground near Cachy and was most familiar with the lie of the land, he led the way. Captain Brown rode with him.

“We left at 8.45am and after a while took off our gas masks. We zigzagged undamaged through a very heavy barrage, reaching the switch line at about 9.30am. An infantryman jumped out of a trench in front of my tank and waved his rifle agitatedly. I slowed down and opened the flap. ‘Look out, there are Jerry tanks about,’ he shouted. This was the first intimation we had that the Germans were using tanks. I gazed ahead and saw three weirdly shaped objects moving towards the eastern edge of Cachy, one about 400 yards away, the other two being much farther away to the south. Behind the tanks I could see lines of advancing infantry.

“At this point Captain Brown left my tank, apparently to warn the females. I turned right and threading my way between the small isolated trenches that formed the Cachy switch line, went in the direction of Cachy. I was travelling more or less parallel to the nearest German tank and my left hand gunner began to range on it. The first shots went beyond but he soon ranged nearer. I noticed no reply from the German tank. There was still a mist overhead but the view on the ground was fairly clear and I was able to use the forward Lewis gun against the German infantry.

“Halfway to Cachy I turned round as the two females were patrolling the other part of the switch line. My attention was now fully fixed on the German tank nearest to me, which was moving slowly. The right-hand gunner, Sergeant J. R. McKenzie, was firing steadily at it, but as I kept continually zigzagging and there were many shellholes, accurate shooting was difficult.

“Suddenly there was a noise like a storm of hail beating against our right wall and the tank became alive with splinters. It was a broadside of armour piercing bullets from the German tank. The crew lay flat on the floor. I ordered the driver to go straight ahead and we gradually drew clear, but not before our faces were splintered. Steel helmets protected our heads.

“A few minutes later I saw Captain Brown out in the open running towards my tank. I stopped. He told me that one of the females had been hit by a shell and had dropped a wounded man in a trench, whom he asked me to pick up. We drove to the spot indicated and took the man on board. He was wounded in both legs and lay on the floor groaning during the rest of the action.

“Nearing the Bois d’Aquenne we turned once more, but owing to the driver’s inexperience and the clumsiness of the secondary gears, the turn was a wide one. Captain Brown again appeared out in the open and hailed me excitedly. ‘Where the hell are you going?’ he yelled through the flap. ‘Back towards Cachy,’ I replied. He then pointed angrily in that direction and to my astonishment I saw the two females retiring from the battlefield.”

In fact, both had found themselves hopelessly outgunned by the German tank. Their machine guns were of little use against the thick armourplating of the enemy, and although they used their greater manoeuvrability to try to find a chink in the opponent’s armour, both were holed and forced to withdraw. Mitchell’s was the only tank left, against three of the enemy.

“I continued carefully on my route in front of the switch line. The left hand gunner was now shooting well. His shells were bursting very near to the German tank. I opened a loophole at the top side of the cab for better observation and when opposite our opponent, we stopped. The gunner ranged steadily nearer and then I saw a shell burst high up on the forward part of the German tank. It was a direct hit. He obtained a second hit almost immediately lower down on the side facing us and then a third in the same region. It was splendid shooting for a man whose eyes were swollen by gas and who was working his gun single handed, owing to shortage of crew.

“The German tank stopped abruptly and tilted slightly. Men ran out of a door at the side and I fired at them with my Lewis gun. The German infantry following behind stopped also. It was about 10.20am.

“The other two German tanks now gradually drew nearer and seemed to be making in my direction. We kept shooting at the nearer one, our shells bursting all round it, when suddenly both tanks slowly withdrew and disappeared in the direction of Hangard.”

And so history was made. Tank had met tank in a gun battle, and the British had won. It was more than a mere duel, however. While the tanks had been thus engaged, the British infantry had been forced back from Villers-Bretonneux, suffering heavy casualties, and held only the southern half of the Cathy switch with the threat of being outflanked by the enemy who had advanced into the Bois d’Aquenne.