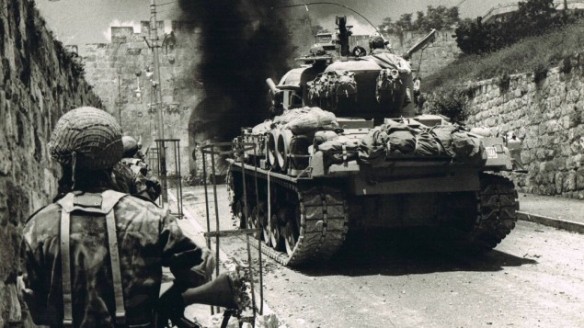

Charging through Lions Gate on June 7, 1967.

Chief Military Rabbi Shlomo Goren at the Western Wall in 1967.

At dawn on Wednesday 6 June 1967 morning, the Israeli high command still had not made the decision to attack the Old City of Jerusalem. By taking most of the surrounding heights the Old City had been isolated. To go in there, through twisting streets no wider than a man’s outspread reach and houses built like rabbit warrens, meant a hard and bloody fight. In essence, reasoned Yitzhak Rabin and the General Staff, if we encircle it and seal it off, the Old City is ours. Most of the West Bank of the Jordan had already fallen to Israeli troops and tanks battling down from Galilee. Ramallah and Hebron had been occupied. The heights of Augusta Victoria were under assault by the paratroops. Unless they contemplated a suicidal last stand, like Custer at Little Big Horn, the Arab Legion had no choice other than surrender.

But events on another far battlefield suddenly changed the course of decision and history in Jerusalem.

The Sinai front had broken wide open. After a wild, bruising clash of men and armor in the coastal defensive position of El Garadi, General Tal’s force had captured the Egyptian air base of El Arish on Tuesday morning. The desert sands were littered with the debris of abandoned and burning vehicles, smashed tanks and gun emplacements. Trucks were twisted into the bizarre black and rust forms of modern sculptures. When it grew dark the desert looked like a vast carnival with bonfires smoldering and sparking all through the night. Dead Egyptian soldiers were sprawled all along the wadis and the dusty Sinai roads.

Abu Agheila had already fallen to General Sharon and his men, who then turned southward toward Nakhl. General Yoffe’s force had split into a pincers movement to take the important junction of Jebel Lidni. After a fierce, all-night tank battle near the airfield there, the position was in Israeli hands by late Tuesday morning. Egyptian prisoners were streaming into camps with their hands clasped behind their heads, or staggering barefoot and with empty water canteens through the inhospitable Ioo- degree desert toward the Suez Canal. The Israeli air force joined the battle in the early afternoon, swooping down to spread destruction and confusion among the retreating columns of armor and vehicles that choked the few roads.

Now the Israeli command in the south deftly baited the final trap. The mass of Egyptian tanks and trucks, including the so-called Shazli Division, Nasser’s finest, still stood in the center of the Sinai Peninsula, virtually intact but fearful of encirclement and annihilation.

There were only three possible avenues of retreat to the Suez Canal and the safety of Mother Egvpt on its west bank. One was to the north along the coastal plain—but this had already been cut off by Tal’s rapid advance westward from El Arish. Another was over the Mitla Pass, which cut a tortuous path through the jagged, lifeless Jebel Tih mountain range running north-south in western Sinai. The third, and most preferable, was to skirt the mountains on the northern fringe through a place called Bir Gafgafa, Egyptian military headquarters in western Sinai.

After the battle of El Arish, Tal’s force split in two. His fastest armor raced for Bir Gafgafa to head off escape in that direction. At about the same time, on Tuesday afternoon, Sharon and Yoffe abruptly slowed the speed of their advance through central Sinai. Grateful for the respite, the Egyptian army accordingly slowed its retreat and made some effort to regroup, giving Tal the time he needed to reach and seal off the Bir Gafgafa exit. Once that was done— by a force of light tanks that outmaneuvered and outgunned the heavier Stalins and T-54s which the Egyptian generals had sent ahead to clear the path— there remained only one possible route to the Canal: the Mitla Pass.

Toward it, then—ruthlessly and relentlessly, through all of Tuesday night and Wednesday morning—Sharon and Yoffe began to drive what was left of the seven armored divisions that were the backbone of what once had been Nasser’s mighty machine of war.

There was to be no escape.

In Jerusalem the Israeli commanders contemplated the situation. The UN, meeting in continuous emergency session in New York, was pressing for an immediate ceasefire. It seemed possible, even probable, that in view of the precarious position of his army in Sinai, Nasser would accept it. King Hussein of Jordan would have to follow suit, and so, undoubtedly, would the Israeli government. The Old City of Jerusalem, even though it was surrounded by Israeli soldiers, would still be garrisoned by the Arab Legion and thus remain Jordanian territory after a ceasefire.

To have done so much and to have achieved so little would be a disappointment and an irony too difficult to suffer. Of what value were the surrounding hills if Yerushalayim Shel Zahav and the Western Wall still remained beyond reach?

Time was running out. At the onset of the war few had seriously believed that Jordan would fight, much less that Jerusalem would be the prize of battle. But now, in the early light of Wednesday morning, as the sun rose over the gold and rose colored walls built by Sultan Suleiman in the sixteenth century, it was the dream in nearly every Jewish soldier’s heart. Somewhere inside those walls lay the Kotel Ma’arabi, the Western Wall. At 9:00 a.m. Dayan, Rabin and Narkis made the historic decision.

The 55th Parachute Battalion was ordered down from the battle for Augusta Victoria, to break into the Old City through St. Stephen’s Gate, which opened outward on the Mount of Olives.

The tanks came first, then the paratroopers crowded into half-tracks. Before reaching the gate, Motta Gur spoke once more to his men. Quietly, but with apparent emotion, he said, “Paratroopers, today we stand at the gates of the Old City—where so many of our dreams lie. hor two thousand years our people have prayed for this moment. Be proud.”

Later, Gur recounted the moment of entry.

“We now started shelling. All our tanks opened fire, as did our recoilless guns. We swept the whole wall and not a shot was directed at, or hit, the Holy Places. The breakthrough area underwent concentrated fire: all the wall shook and some stones were loosened—but all the firing was to the right of St. Stephen’s Gate… .

“I told my driver, Ben Tsur, a bearded fellow weighing some two hundred and twenty pounds, to speed on ahead. We passed the tanks and saw the gate before us with a car burning outside it. There wasn’t a lot of room, but I told him to drive on and so we passed the burning car and saw the gate half open in front. Regardless of the danger that somebody might drop grenades into our halftrack from above, he pushed on and flung the door aside, crunched over the fallen stones, passed by a dazed Arab soldier and turned left. Here a motorcycle blocked the way. But despite the threat of booby-trapping, my driver drove right over it, and so we reached the Temple Mount… .”

The troops following Gur rushed the gate, at first meeting with only weak resistance, for the tanks had knocked out the enemy positions on the perimeter. Nevertheless, from behind the Al-Aksa Mosque, a legion post kept letting off bursts of machine-gun fire in the direction of the Israeli soldiers, while well-concealed snipers kept popping away.

Larry Levine’s company was again in the lead. They turned left toward the mosque. In the courtyard of the mosque the legion had established a defensive position and had set up some tents. But the tents were empty and the Jordanian soldiers had gone. Civilians began emerging from the houses and shuttered shops, hands raised over their heads, and a detail was left to guard them. The paratroopers continued to advance cautiously up the Via Dolorosa, a steep, shadowed street full of closed souvenir shops, which led from the Gate toward the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. At the second intersection, the lieutenant commanding Larry’s platoon stepped from the shelter of a doorway to reconnoiter and was killed instantly by a sniper’s bullet.

“Hold up,” yelled Isaac, the captain. “We don’t even know where we are. Who knows this area?”

It had been a good twenty years since any Jew had been inside the Old City. The soldiers were mostly young men, and they suddenly realized they had no idea where the Wailing Wall was, or—in that labyrinth of narrow streets and alleyways—how to set about getting there.

Larry Levine and another soldier saw a movement behind a doorway. They broke in, without firing, and found an old man huddled on a staircase. Larry, who had learned Arabic from the Israeli Arabs who sometimes came from the nearby village at harvest time to work on his kibbutz, said to the man at gunpoint, “Salaam aleichem, bey. We’re going to the Western Wall. And you’re going to take us there.”

Led by the old Arab, the paratroopers threaded their way through rubble and tangles of barbed wire, with an occasional bullet whistling over their heads, squeezed through an aperture in an ancient building, went down some stairs, crossed a courtyard and passed some mud hovels, and finally rounded a corner and saw, towering over their heads, the Wall.

The Kotel Ala’Arabi had seen emperors and kings, wise men and sultans, shaven women and bearded rabbis trembling with religious exaltation, but it had never seen bloodstained, sweating, weeping paratroopers. The men who for two days had battled the Arab Legion and the Palestine commandos, the men who had never hesitated to assault a strongpoint again and again until they had broken through, stood and suddenly, uncontrollably, sobbed aloud. The tears were born of emotion and release, and a partial inability to understand the reality of what their eyes saw. They seemed, in a sense, to be the tears of nineteen hundred years of separation from something holy and beloved.

The captain made his way through the buildings and along the roofs to the top of the wall, where he hung the blue and white Israeli flag with its Star of David. At the bottom of the wall, which rose some seventy feet, some of the men moved forward to caress the great slabs of stone. The stones had been worn smooth by the touch of millions of hands through the centuries. Others kneeled to pray. Others simply stared. Then all— those who cried, those who prayed, those who stared— spontaneously embraced and kissed each other’s stubbled cheeks.

“It’s ours,” one man said, his voice a whisper full of triumph and awe. “Jerusalem—is—ours.”

A few minutes later, oblivious of the sniper’s bullets which still flew, the chief rabbi of the army, General Shlomo Goren, came racing through St. Stephen’s Gate in a jeep and rushed on foot down the path to the wall. There he offered a Hebrew prayer and, drawing forth a shofar, the horn normally sounded only on the most solemn of Jewish Holy Days, he blew a long and powerful blast. He was followed seconds later by Moshe Dayan, Yitzhak Rabin and then by the prime minister, Levi Eshkol.

By noon the fight for the Old City was over. There were still isolated pockets of resistance, and snipers were every Army Chief Chaplain Goren blowing the shofar near the Western Wall where, but their number dwindled steadily as the exhausted troops moved methodically from house to house, street to street, mopping up. In effect, all of Jerusalem was in Israeli hands.

At two o’clock in the afternoon Larry Levine’s company had reached the part of the encircling wall which faced the King David Hotel in what had been the Israeli half of the city. Climbing the wall, they raised the Israeli flag. From a captured Arab Legion barracks they hoisted two great parade drums to the parapet.

“We stood up on the wall,” Larry said afterward, “and began beating the drums. Boom, boom, boom! Each different company had hung up the Israeli flag, and all along the towers the flags were waving in the wind. A whole bunch of women and kids that were in air-raid shelters on the Israeli side came out—and we stood there, and everybody’s cheering and hollering, and we’re banging on this great big bass drum. Boom, boom, boom! And they were dancing in the street, and they were crying and kissing each other and yelling and jumping up and down. They all realized we had the city. We had Jerusalem. They had this chant you hear all the time for the Israeli team in the international soccer matches. It goes: ‘El! El! Yis-ra-el! El! El! Yis-ra-el!’ And the kids in the street started to shout it in time with the boom boom of the drums. ‘El! El! Yis-ra-el! El! El! Yis-ra-el!’

“You couldn’t believe it. We started to cry all over again, grown men, for the third time in three days, at the same time as we were banging on this drum. Because so many of our guys, good guys that we loved, were dead. But we’d won. And the people, our people, even the kids, knew it. And they were so happy. And that seemed to be worth … everything.”