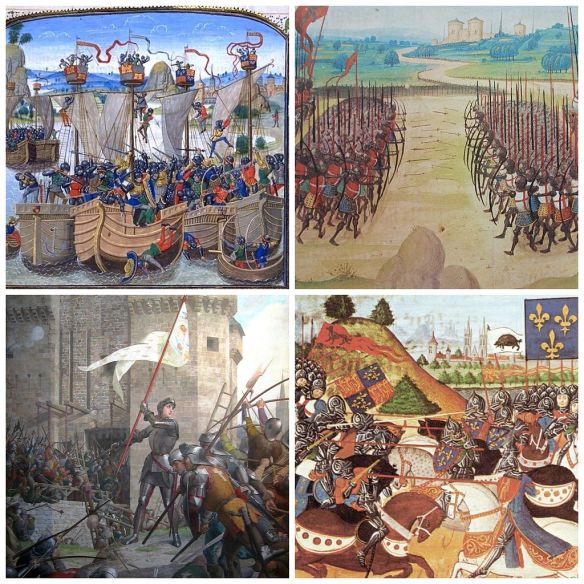

Clockwise, from top left: The Battle of La Rochelle, The Battle of Agincourt, The Battle of Patay, Joan of Arc at the Siege of Orléans.

The Hundred Years’ War was not given that name until the nineteenth century, and in fact, these wars lasted one hundred sixteen years. But it is an appropriate enough title for the long-drawn-out series of conflicts that took place between France and England from 1337 to 1453. The war was fought essentially for dynastic reasons: to determine which royal family would control France. Ever since the Norman Conquest, the English royals had retained extensive lands in France and increasingly this became a bone of contention. When the French King Charles IV died in 1328, the English King Edward IV, grandson of former French King Philip IV and ruler of the duchy of Guyenne—in the region of Aquitaine in southwestern France—laid claim to the French throne. However, a French assembly gave the crown to the rival French claimant, Philip, Count of Valois. Subsequently crowned Philip VI, he declared Guyenne confiscate in 1337, triggering hostilities.

Historians traditionally divide the war into four phases. In the first phase (1337—60), the English were surprisingly successful, given that their country was poorer and less populous than France, they were fighting abroad, and their forces were smaller than their enemy’s. In part, this success was due to the English men-at-arms, who were particularly well disciplined and were accompanied by longbowmen, whose fearsome fire-power helped make up for their army’s lack of numbers.

France also had a larger navy, but at sea, too, the English triumphed initially, winning a great naval victory at Sluys in 1340 that neutralized the French fleet for the remainder of the war. In 1346, Edward scored another major victory at the battle of Crécy, and in 1347 he captured the port of Calais. At this point, a truce was arranged with the help of the pope, both armies by then war-weary and affected by bubonic plague. Three years later, however, Philip died, to be succeeded by John II. In 1356, Edward’s son, Edward Woodstock, known to history as the Black Prince launched an attack on France, reigniting the conflict. Within the year, he defeated King John II at Poitiers and took him hostage, forcing the French to sue for peace. The Treaty of Brétigny of 1360 obliged the French to pay three million gold crowns to the English—John II’s ransom—and gave England control of nearly half of France. In return, Edward renounced his claim to the French throne.

However, John died in captivity before the terms of the treaty were fulfilled, and his son and successor Charles V soon reopened hostilities, beginning the second phase of the war (1369— 99). At last providing France with effective leadership, Charles first invaded Aquitaine, whose inhabitants were being heavily taxed by the Black Prince. Then, under the brilliant general Bertrand du Guesclin, the French took Poitiers, Poitou, and La Rochelle by 1372, and Aquitaine and Brittany by 1374, thus regaining all of the land ceded under the Treaty of Brétigny and leaving England with only Gascony and Calais. The Black Prince died in 1376, Edward III in the following year, and the second phase of the war became almost entirely a French victory. But then Charles died of a heart attack in 1380 and the conflict petered out. The Truce of Leulinghen of 1389 allowed the two sides to recover and regroup.

The third phase of the war (1399—1429) has been compared to a “cold war” by some historians, for following the 1399 deposition of the unpopular Richard II in England, who had succeeded Edward III, and the French King Charles VI’s descent into madness around the same time, factions on both sides began trying to undermine the other country. And even though the Truce of Leulinghen officially remained in place, English raids resumed during the short reign of Henry IV (1399—1413). In 1415, Henry V captured the port of Harfleur, then won a great and famous victory at Agincourt; by 1419, he had conquered all of Normandy. The Treaty of Troyes of 1420 made Henry heir and regent of France. But in 1422, before he could assume the throne, he died (just a few weeks before Charles), leaving John, Duke of Bedford, to rule as regent for his six-year-old son, Henry VI. The new English king was recognized as King of France north of the Loire River. South of the Loire, however, the French population continued to support Charles VI’s son, Charles, who initially remained uncrowned, with the title of dauphin, or heir. So English forces laid siege to the dauphin’s stronghold of Orléans in 1428 in an attempt to gain control of the rest of France.

The fourth phase of the war began in 1429, when the charismatic Joan of Arc rallied French forces to lift the siege. The dauphin was crowned Charles VII at Reims in the same year, and the French then achieved a series of victories, liberating Paris and the Ile-de-France (1445—48), Normandy in 1450, and Aquitaine in 1453, and crushing a major English force at the battle of Castillon, also in 1453. No formal peace treaty ended hostilities between the two countries: England simply recognized that France was now too strong to attack successfully.

By the end of the war, the English government was nearly bankrupt. A series of civil wars ensued in England, fought between rival claimants to the throne and known as the Wars of the Roses. Of their lands in France, the English retained only Calais, which they were forced to relinquish in 1558. Despite the defeat, successive English monarchs referred to themselves as the King or Queen of France until 1802. The French, though victorious, bore the scars of English depredations, and the resulting resentment and enmity between the two countries lasted for centuries.

ONE WOMAN SAVES A BESIEGED CITY—AND CHANGES THE OUTCOME OF A WAR

Joan of Arc (c.1450–1500)

The Siege of Orléans, 1428-29

To the besieged French looking down from the walls of the city of Orléans on that bright, cold spring day of April 29, 1429, the woman astride the white charger must have seemed like an apparition. Tiny and black-haired, she was dressed in a suit of shining white enamel armor made especially for her, and she held aloft her pennon, a narrow banner of blue and white emblazoned with two angels and a single word: Jesus.

Following behind Joan of Arc—as we know her today, although the French at the time called her “the Maid,” or la Pucelle, the Virgin—was a processional force of some two hundred lancers. And encamped outside the walls of the city were another five thousand men, who had followed Joan across France in order to save the city of Orléans—and the entire country—from the English.

The Maid was the strangest commander these men had ever had. She attacked the prostitutes who followed the army with the flat of her sword, forbade the men to swear, and wore her heavy armor at all times, to the amazement of at least one knight: “She bears the weight and burden of her armor incredibly well, to such a point that she has remained fully armed for six days and nights.”

And magic seemed to follow the Maid. At the town of Ferbois, along the army’s route, a town she had never before entered, she ordered the clergy at St. Catherine’s Church to dig up a stone at the rear of the altar. They would find a sword there, she told them. And they did, a rusting relic of some bygone century. The soldiers were astonished, although those who knew Joan a little better understood that St. Catherine was one of the trio of saints who spoke to her almost daily.

When Joan of Arc entered Orléans with her lancers on that evening in April, a huge crowd of men, women, and children gathered, carrying torches, shouting and laughing. For, as one chronicler wrote, “they felt themselves already comforted and as if no longer besieged, by the divine virtue which they were told was in this simple maid.”

The Last Stronghold

Joan of Arc had arrived on the scene at one of the most critical junctures of the Hundred Years’ War. Responding to the refusal of the French population south of the Loire River to accept the rule of their young king, Henry VI, English forces, under the Duke of Bedford and his field commander, the Earl of Salisbury, had begun a major southward offensive in 1422. Routing the French as they went, they advanced steadily and by 1428 were on the brink of victory.

In October, Bedford sent Salisbury, at the head of five thousand men, to capture the city of Orléans, on the north bank of the Loire. This city controlled the chief passage to this important waterway and was the last stronghold of the French forces loyal to the dauphin.

Despite their previous victories, the English had no assurances of conquering Orléans. The city was formidable. Situated on the north bank of the river, it was surrounded by walls 30 feet (9 m) high surmounted by at least seventy cannons, some of which shot stones weighing 200 pounds (90 kg). Inside were 2,500 troops and 3,000 militia—a force that outnumbered the English because Salisbury had lost at least 1,000 of his men through desertion on the way to Orléans.

Salisbury could not possibly blockade Orléans or even surround it, given his small force. So, he set up a strong infantry position on the south bank of the river and fortified the gatehouse known as Les Tourelles at a bridge leading to the city. On the north bank, east and west along the river, he placed a semicircle of six stockades.

In mid-October English gunners sent cannon shots into the streets, scattering its inhabitants. The battle was on. And if Orléans fell, France would fall, too.

There then ensued one of the strangest sieges of the war, a haphazard and oddly leisurely affair for both sides. Soon after it began, Salisbury was killed by a lucky French cannon shot and replaced by the Earl of Suffolk. Far less aggressive than Salisbury, he took most of his troops into winter quarters, leaving only a small force at Les Tourelles. Suffolk’s superiors then forced him to bring his men back and create a network of sixty breastworks, topped by palisades and connected by communications trenches. But Suffolk left a wide gap in the defenses to the northeast, through which the French could receive supplies. He also neglected to block river traffic, and thus troops and supplies could move into Orléans by boat almost at will.

As a result, the defenders of the city, well fed and feeling no particular urgency to either attack or escape, simply bided their time. And the English did much the same. On Christmas Day, a truce was called from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., and French musicians came through the gates of Orléans to play music for the English troops.

After her arrival, Joan, having rested a night and prayed at the cathedral, tried to convince the commander of the garrison, the Comte de Dunois, otherwise known as the Bastard of Orléans, that he should foray out to attack the English. Dunois, still mistrustful of this strange and charismatic young woman, refused, and instead set out to seek reinforcements. After he left, Joan—trying to raise the spirits of the French garrison—rode out to within shouting distance of the English forces. She was enraged because she had earlier sent the English a note carried by her herald, Guyenne, whom the English had taken prisoner, in contravention of the knightly code of conduct, and were now threatening to burn at the stake, on the basis that he was a familiar of the “witch,” Joan.

When Joan shouted at the English to surrender, they merely laughed at her, calling her a “cow-girl” (even though Joan had herded sheep, not cows) and the French who were with her “pimps.” They threatened to have her burned when they caught her.

When Dunois returned on May 4 with reinforcements, Joan “sprang to her horse,” as one of the knights present said, and galloped to meet him outside the city. Finally they could attack the English, she urged Dunois. When he would still not lead a large-scale attack against the enemy, Joan went to her chambers to take a nap, but after a short time awoke and told her aide, “In God’s name, my counsel has told me to go out against the English.” Joan’s “counsel” was her trio of saints, and when they spoke to her she could not be stopped. She put on her armor and raced out of Orléans.

A small French force was skirmishing with the enemy outside the English bastion of St. Loup; Joan stormed into the melee and ferociously led a charge that caused the fortress to fall. But she was now confronted, for the first time, with the carnage of war. Appalled by the sufferings of the dead and dying—both French and English—she began to weep, distraught that these men had not made a confession before they died. She took one Englishman who had been run through by a sword and cradled him in her arms until he passed away.

A Frenzied Attack

Reading the story of Joan at Orléans—much of it in the form of testimony at the trial for heresy that resulted in her execution at the stake—one is struck by the contrast between Joan’s energy and fervor and the cautiousness of the leaders around her. After resting on the Feast of the Ascension, Joan made another attempt to rescue Guyenne, writing a note to the English and having it attached to an arrow and shot into the enemy camp. It read, in part, “You, Englishmen, who have no right in this Kingdom of France, the King of Heaven orders and commands you, through Joan the Maid, that you quit your fortresses and return to your own country… You [hold] my herald named Guyenne. Be so good as to send him back.”

The English responded by shouting that Joan was a whore. When she heard this, she began to cry, as she did on many occasions when insulted. But the next day, she rose early, confessed her sins, and took her men out of the city to attack another bastion, St.-Jean-le-Blanc, which covered the approaches to Les Tourelles. The English were so surprised that they abandoned the bastion immediately, fleeing toward a stronger and far larger fortress, a monastery called Les Augustins. In a wild frenzy of fighting, with Joan alternately shouting to the Lord and weeping, the French gave chase and took Les Augustins as well, tearing down the English banners and replacing them with French ones. A great cheer arose from the city of Orléans as the English retreated now to Les Tourelles, their strongpoint on the bridge.

An Inspiring Tableau

The next day, May 7, at about 8 a.m., Joan led a force in a direct frontal attack on the fortified towers of Les Tourelles. This was perhaps her greatest act of bravery. The evening before, she had predicted to her confessor that she would be wounded in the assault—“tomorrow the blood will flow out of my body above my breast,” she said—but despite the fact that she was clearly terrified, she mounted her horse and led the men in the first attack. She was soon struck just below the shoulder by an arrow, as she had predicted, and the English archers on the walls laughed and shouted curses as she was carried off the field. Some of the Frenchmen handed her magic amulets to protect her, but she shoved these away angrily and had her wound—which was not deep—treated with lard and olive oil. Her armor dirty and her hair disheveled, she then gave confession to her priest in a highly emotional state before resting.

Repeated French assaults failed to dislodge the English, and the Bastard of Orléans decided to call off the attack for the day. When Joan heard this, she refused to allow him to give the order and prepared to return to battle.

There now occurred one of the most extraordinary moments in French history. Joan’s standard-bearer, exhausted after the day-long fighting, had given Joan’s pennon to a soldier known to history only as the Basque. The Basque and another brave French knight had reached the base of the bridge across the Loire, near the bottom of the towers of Les Tourelles, and found a wooden ladder they could climb to the bridge’s roadway. As they started to climb, Joan arrived and demanded her banner back, crying, “My standard! My standard!” But instead of handing it over, the Basque raised it higher.

The French soldiers saw this tableau—Joan reaching for her banner, the Basque holding it up in the air—and, shouting almost as one voice, raced for the bridge with their assault ladders. Joan was on the first one placed there. Despite heavy fire from Les Tourelles, the French swarmed up to the roadway and attacked the English soldiers there, with Joan crying out, “Classidas, Classidas [the English commander] yield thee, yield thee to the King of Heaven, thou [who] has called me ‘whore.’”

Classidas, fully armored, fell into the river and drowned during the chaos of the assault. Hundreds of other Englishmen also died at the hands of their foes or in the river, before the French, led by the triumphant Maid, finally carried the day.

The siege was broken. The next day, the English burned their stockades and marched away. And the French people, according to French knight Jean d’Aulon, who was there and later testified at Joan’s trial, “made great joy, giving marvelous praises to their valiant defenders and above all others to Joan the Maid.”