Eldest daughter of Alfred the Great, sister of Edward the Elder, and aunt and fosterer of Aethelstan, Aethelflaed of Mercia (d. 918) led troops against the Vikings, built forts, endowed churches, issued charters, dealt with Irish-Norwegian pressures, and received the submission of the men of York. When her husband Aethelred died (911), she became the sole political and military authority in Mercia, working, as she and her husband had done earlier, in cooperation with Edward the Elder and recognizing his overlordship as King of Wessex. (In fact, given Aethelred’s apparent illness and incapacity, Aethelflaed was de facto in power beginning c. 902.) This cooperation was ultimately successful in eliminating the Danish threat to Anglo-Saxon England and paved the way for the eventual unification of Mercia and Wessex.

The primary evidence for Aethelflaed’s achievements occurs in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in versions B, C, and D. Versions B and C present a “Mercian Register” or an “Annals of Aethelflaed,” perhaps based on a now-lost Latin source. This section violates the chronological order in B and C, and suddenly introduces a focus on Mercia. Aethelflaed is styled “Lady of the Mercians,” which some scholars take as a semantic dodge for “queen,” possibly reflecting uneasiness with queens (Alfred’s wife Ealhswith never had the title) or downplaying royal aspirations in the face of Edward. The clumsy insertion of the Mercian Register in B and C compares with its smoother incorporation in D, where Aethelflaed’s exploits are diminished and folded into the story of the House of Wessex.

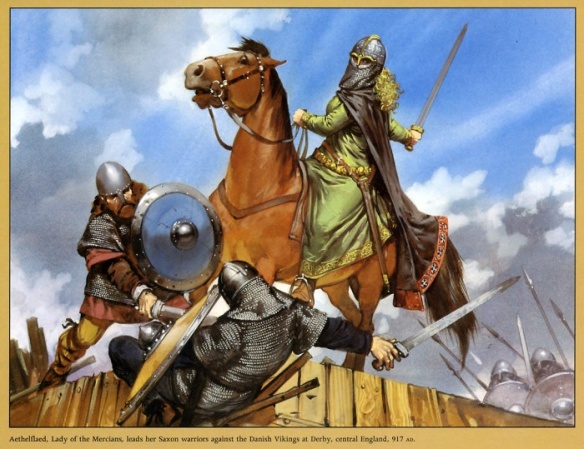

THE LADY OF THE MERCIANS

There is a battered silver penny from King Alfred’s reign on which is inscribed the grand Latin title REX ANGLO[RUM] – `King of the English’. But the claim was only half true. Alfred had been King of those Angel-cynn, the kin or family of the English, who lived in Wessex, and his resourcefulness had kept Englishness alive in the dark days when the Viking forces drove him and his people into the Somerset marshes. The work of extending Anglo- Saxon authority across the whole of Engla-lond, as it would come to be known, was done by Alfred’s children and grandchildren – and of these the most remarkable was his firstborn, his daughter Aethelflaed, whose exploits as a warrior and town-builder won her fame as the ¡¥Lady of the Mercians.

In this year English and Danes fought at Tettenhall [near Wolverhampton], and the English took the victory, reported the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 910. And the same year Aethelflaed built the stronghold at Bremsbyrig [Bromsberrow, near Hereford].

Women exercised more power than we might imagine in the macho society of Anglo-Saxon England. The Old English word hlaford, lord, could apply equally to a man or a woman. The abbess Hilda of Whitby (Caedmon’s mentor), who was related to the royal families of both Northumbria and East Anglia, had been in charge of a so-called ¡¥double house¡¦,where monks and nuns lived and worshipped side by side and where the men answered to the abbess, not the abbot.

The assets and chattels of any marriage were legally considered the property of both husband and wife, and wills of the time routinely describe landed estates owned by wealthy women who had supervised the management of many acres, giving orders to men working under them. King Alfred’s will distinguished rather gracefully between the spear and spindle sides of his family. It was women’s work to spin wool or flax with a carved wooden spindle and distaff, and the old king bequeathed more to his sons on the spear side than to his wife and daughters with their spindles. But he still presented Aethelflaed with one hundred pounds, a small fortune in tenth-century terms, along with a substantial royal estate.

Aethelflaed turned out to be an Anglo-Saxon Boadicea, for like Boadicea she was a warrior widow. Her husband Ethelred had ruled over Mercia, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom that had spread over most of the Midlands under the great King Offa in the late 700s. Extending from London and Gloucester up to Chester and Lincoln, Mercia formed a sort of buffer state between Wessex in the south and the Danelaw to the north and east, and the couple had made a good partnership, working hard to push back Danish power northwards. But Ethelred was sickly, and after his death in 911 Aethelflaed continued the work.

In this year, by the Grace of God, records the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 913, Aethelflaed Lady of the Mercians went with all the Mercians to Tamworth, and built the fortress there in early summer, and before the beginning of August, the one in Stafford.

It does not seem likely that Aethelflaed fought in hand-to-hand combat. But we can imagine her standing behind the formidable shield wall of Saxon warriors, inspiring the loyalty of her men and winning the awed respect of her enemies. She campaigned in alliance with her brother Edward, their father’s successor as King of Wessex, and together the brother and sister repulsed the Danes northwards to the River Humber, thereby regaining control of East Anglia and central England. To secure the territory they captured, they followed their father’s policy of building fortified burhs.

Aethelflaed built ten of these walled communities at the rate of about two a year, and their sites can be traced today along the rolling green hills of the Welsh borderland and across into the Peak District. They show a shrewd eye for the lie of the land, both as defensive sites and as population centres. Chester, Stafford, Warwick and Runcorn all developed into successful towns – and as Aethelflaed built, she kept her armies advancing northwards. In the summer of 917 she captured the Viking stronghold of Derby, and the following year she took Leicester and the most part of the raiding-armies that belonged to it, according to the Chronicle. This was the prelude to a still more remarkable triumph: The York-folk had promised that they would be hers, with some of them granting by pledge or confirming with oaths.

The Lady of the Mercians was on the point of receiving the homage of the great Viking capital of the north when she died, just twelve days before midsummer 918, a folk hero like her father Alfred. She had played out both of the roles that the Anglo-Saxons accorded to high-born women, those of peace-weaver and shield-maiden, and her influence lived on after her death. Edward had had such respect for his tough and purposeful big sister that he had sent his eldest son Athelstan to be brought up by her – a fruitful apprenticeship in fortress-building, war and busy statecraft that also helped to get the young Wessex prince accepted as a prince of Mercia. After his father’s death in 924, Athelstan was able to take control of both kingdoms.

Athelstan proved a powerful and assertive king, extending his rule to the north, west and south-west and becoming the first monarch who could truly claim to be King of all England. In his canny nation-building could be seen the skills of his grandfather Alfred and his father Edward, along with the fortitude of his remarkable aunt, tutor and foster-mother, the Lady of the Mercians.

References and Further Reading Bailey, Maggie. “Aelfwynn, Second Lady of theMercians.” In Edward the Elder, edited by N. J. Higham and D. H. Hill. London and New York: Routledge, 2001, pp. 112-127. Keynes, Simon D. “Edward, King of the Anglo-Saxons.” In Edward the Elder, edited by N. J. Higham and D. H. Hill. London and New York: Routledge, 2001, pp. 40-66. Szarmach, Paul E. “Aethelfaed of Mercia: Mise en Page.” In Words and Works: Studies in Medieval English Language and Literature in Honour of Fred C. Robinson, edited by Peter S. Baker and Nicholas Howe, Toronto, Buffalo, and London: University of Toronto Press, 1998, pp. 105-126. Thompson, Victoria. Dying and Death in Later Anglo- Saxon England. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2004. Wainwright, F. T. “Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians.” In New Readings on Women in Old English Literature, edited by Helen Damico and Alexandra Hennessey Olsen. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1990, pp. 44-55. Originally published in The Anglo-Saxons: Studies in Some Aspects of the History and Culture, Presented to Bruce Dickins, edited by Peter Clemoes. London: Bowes and Bowes, 1959.