Hitler, meanwhile, ordered Rundstedt to restore the line and “to fight for time so that the West Wall can be prepared for defence.” He also ordered him to launch an attack from the Epinal area against the right flank of Patton’s 3rd Army, regardless of losses.

General Student never had a chance to hold the 60-mile-long Albert Canal line. It would take at least a week for most of his new regiments to reach the front, and the British had already breached the canal line by September 6. He was, however, also given command of the Wehrmacht forces in the Netherlands, and owing to the British supply difficulties, Student felt that he might be able to establish a thin front near the Dutch-Belgian border.

Field Marshal Model, meanwhile, turned his attention to the rescue of the 15th Army-the strongest army left in Army Group B. It had been under the command of General von Zangen since the anti-Nazi General von Salmuth had been sacked on August 25, and it had 90,000 men, 600 guns, and more than 6,200 vehicles and horses. It was no longer possible for it to escape solely by land, however. To make good its getaway, 15th Army would have to cross the Scheldt estuary-a boat trip of 3.5 miles from Breskens to Flushing on Walcheren Island. The trip would be 13 miles for troops departing from Terneuzen. From Flushing, the troops would have to march over a narrow, open, unprotected causeway that connected Walcheren Island with South Beveland peninsula; then they would have to take a single road that led to the mainland, 15 miles north of Antwerp. (Had the British just driven 15 miles north after capturing Antwerp on September 3, they would have cut off the escape route of the 15th Army. The speed of their breakthrough had so surprised the Germans that there had been no troops in the critical sector at that time, but, like the Americans, the British were engaging in “pursuit thinking” and missed a major opportunity.) All of this would have to be gone in the flat, open terrain of the Netherlands in the face of an enemy who had absolute control of both the sea and the air. Even if everything went perfectly, it would take at least three weeks to complete the evacuation. Undaunted, Zangen posted a strong rear guard to check the Canadian and British forces advancing in his rear, and started the evacuation on September 6.

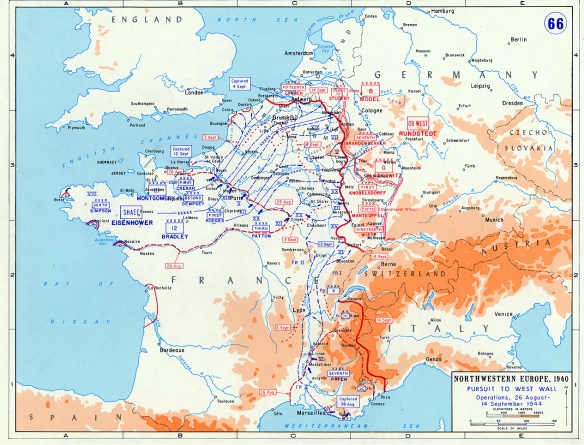

Elsewhere, the battered units from Normandy were still trying to escape the Montgomery’s juggernaut, which (unlike Patton’s 3rd Army) had not yet completely run out of gas. On Montgomery’s left flank, the 1st Canadian Army sealed off most of the escape routes of Zangen’s 15th Army and besieged the ports of Le Harve, Dunkirk, Calais, and Boulogne and overran the V-1 sites around Pas de Calais. In his center, Dempsey’s 2nd British Army advanced north of Antwerp, across the Albert Canal and the Meuse. On his right flank, Hodges’s 1st U. S. Army took Mons on September 3 and surrounded the remnants of several German divisions and three German corps headquarters: the LXXIV (Straube), the LVIII Panzer (Krueger), and the I SS Panzer (Keppler). As the senior general, Straube assumed command of the encircled forces, which were much more interested in escaping than fighting.

Straube ordered his disorganized forces to break out, and a great many did, but 25,000 were captured. The U. S. IX Tactical Air Command later claimed the destruction of 851 motorized vehicles, 50 armored vehicles, and 652 horse-drawn vehicles in the Mons Pocket. All three corps commanders escaped, along with their staffs, but several divisions were smashed, including the elite 6th Parachute Division, which went into the battle with a combat strength of only two battalions. Its commander, Lieutenant General Ruediger von Heyking, was among the prisoners. Its sister division, the 3rd Parachute, was at less than regimental strength but managed to escape, thanks to the leadership of its acting commander, Major General Walther Wadehn. Lieutenant General Joachim von Treschow of the 18th Luftwaffe Field Division also escaped, but only 300 men came out of the pocket with him: Most of them preferred to surrender to the Americans.

The 18th Field was dissolved after Mons. Major General Karl Wahle of the 47th Infantry Division and Lieutenant General Paul Seyffardt of the 348th Infantry succeeded in escaping the pocket but were captured before they could reach the safety of the West Wall. The 47th Infantry had to be rebuilt as a Volksgrenadier Division, and the remnants of Lieutenant General Eugen-Felix Schwalbe’s 344th Infantry Division (which was also at Mons) had to be taken out of the line. Later it absorbed the remnants of the 91st Air Landing Division and elements of the 172nd Replacement Division and reemerged as the 344th Volksgrenadier Division. The 271st Infantry-also mauled at Mons-was sent to Slovakia, where it absorbed the 576th Volksgrenadier Division and was sent to the Eastern Front as the 271st Volksgrenadier Division. Other German units were also pounded as they tried to reach the frontier. Kurt Meyer, who had spent years in the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (Hitler’s SS bodyguard unit, now the 1st SS Panzer Division), visited his old outfit on August 20 and barely recognized it, so few of the “old hands” were left. When he heard who was missing or dead, tears poured down his cheeks. Indeed, Normandy was, in a very real sense, the graveyard of the Waffen- SS as an elite fighting force.

After Normandy, the Waffen-SS divisions had lost so many of their bravest men and best leaders and veterans, and Himmler and General of SS Gottlob Berger, the chief of the SS Central Office, were filling their places with so many substandard replacements, that they never performed at quite the same level again. After Normandy, the SS divisions lost much of their former eliteness.

In the meantime, the Allies’ pursuit was slowing. On September 3, the U. S. 9th Infantry Division of Collins’s VII Corps crossed the Meuse just south of Dinant, expecting no resistance. They were suddenly pounced upon by elements of the tough 2nd SS Panzer Division and the remnants of the 12th SS Panzer Division “Hitler Youth,” both operating under Keppler’s I SS Panzer Corps. One U. S. battalion was partially surrounded and lost more than 200 men. The 9th Infantry was forced to cling to a small foothold on the east bank for a day and a half before it could be rescued by a task force from the U. S. 3rd Armored Division, coming down from the north. Even so, Dinant was not captured until the morning of September 7. During this battle, the remnants of the 77th Infantry Division (about 4,000 men) were finally encircled and destroyed.

The Allied advance continued, and the U. S. VII Corps took Liege on September 7, but resistance seemed to be stiffening. To the south, Bastogne was captured by Leonard Gerow’s U. S. V Corps on the September 8. Luxembourg, the capital of the Grand Duchy by the same name, was occupied on September 10, and by September 11, Malmedy was in American hands. The American soldiers were now in the Ardennes, only a few miles from the German border, and there was a noticeable chill in the air, not attributable solely to the changing season. A few days before, one American soldier wrote of a liberated town: “Once again cognac, champagne, and pretty girls.” His tone was slightly bored because he had come to expect such things. Now, however, the attitude of the civilians had changed. “There were no more V-for-Victory signs, no more flowers, no more shouts of ‘Vive l’Amerique,’ ” Blumenson recalled. “Instead, a sullen border populace showed hatred, and occasional snipers fired into the columns.” Meanwhile, the XIX Corps of Hodges’s 1st Army ran out of gas and was immobilized for several days. The U. S. 5th Armored Division continued to push forward, however, and on the evening of September 11, one of its patrols crossed the German frontier near Stalzenburg. The Americans probed deeper the next day and discovered that the West Wall opposite the Ardennes was weakly manned and some of its fortifications were not occupied at all. Supply difficulties prevented an attack until September 14, however, and by that time, the situation had fundamentally changed. Model had been able to reinforce the threatened sector, and the American attack, which penetrated the first line of defenses, was beaten back to the outskirts of Pruem. The Americans were finally halted on the very fringes of the West Wall.

Meanwhile, along the coast, the 1st Canadian Army (with six divisions) captured the city of Rouen (near the mouth of the Seine) on August 31, took the minor ports of Dieppe and Ostend a few days later, and prepared to attack the major Channel ports of Le Havre and Pas de Calais. In the zone of the British 2nd Army, the VIII British Corps, with two infantry divisions, two tank brigades, and most of the army’s heavy and medium artillery, was still on the Seine, immobilized due to a lack of gasoline. The XII British Corps was still engaged in driving into the rear of Zangen’s 15th Army but was meeting unexpectedly fierce resistance. This meant that out of the 14 divisions and seven armored brigades in 21st Army Group, Montgomery had only one corps left with which to continue the advance into Holland: Horrocks’s XXX, with the 11th and Guards Armoured Divisions. It was not strong enough to sustain the momentum of the drive.

South of the Ardennes, Patton was also running into serious problems. His army had been largely immobilized due to a lack of fuel for several days. When he was at last able to resume his offensive on September 5, German resistance was no longer weak to nonexistent: It was very tough. One American effort to cross the Moselle (at Pont-a-Mousson) was beaten back with heavy losses, and although one U. S. force was able to seize Toul in the Moselle bend, the U. S. 3rd Army in general was tied down in heavy fighting between Metz and Nancy. Patton’s great advance had also come to an end. It was the same story everywhere: Just as suddenly as it had started, it stopped. The Wehrmacht was no longer “on the run.” Despite the Mons Pocket, Army Group B had managed to escape and was now digging in behind the West Wall. Army Group G (19th Army and LXIV Corps) had also escaped, bringing most of its combat units out with it, more or less intact. The two army groups linked up on September 12, establishing a continuous front from the North Sea to the Swiss border. Most of it was behind the West Wall (called the Siegfried Line by the Allies), which extended from the Dutch border near Kleve to the Swiss frontier, just north of Basle. The Germans once again had a continuous front, although it was not thickly held.

June, July, and August 1944 had been a disastrous period for the Third Reich. It had lost 55,000 men killed and 340,000 missing in the West and 215,000 killed and 627,000 missing on the Eastern Front. Counting wounded (which generally amounted to three times the number killed), the total casualties amounted to 2,047,000. OB West had also lost the use of 200,000 more men, cut off in Hitler’s so-called fortresses on the Atlantic coast. The 2-million-plus casualties suffered from June to September were roughly equal to the losses the Wehrmacht suffered from the start of the war to February 1943, including Stalingrad. A quarter of a million horses had also been lost. Some 29 divisions had been lost or rendered impotent (including those trapped in the coastal fortresses), and 3 divisions had been disbanded in the Balkans, 2 in Italy, and 10 in the east, making the total losses for the three-month period 44 divisions. In all, the Reich would lose 106 divisions in 1944-more than it had in 1939.