Lt. Col. Bisshopp’s Raid on Black Rock in the War of 1812.

(June 25, 1783–July 16, 1813) English Army Officer

A dashing leader, Bisshopp served as an infantry officer as well as inspector general of the Upper Canada militia during the War of 1812. He conducted numerous successful raids along the Niagara frontier before losing his life in a protracted skirmish.

Cecil Bisshopp was born in Parham House, West Sussex, on June 25, 1783, the son of a baronet and former member of Parliament. He belonged to an ancient, landed family and, as the only surviving son, stood to inherent an impressive fortune. However, Bisshopp was drawn quite early to the military profession, and in September 1799 he obtained an ensign’s commission in the prestigious First Foot Guards. Over the next 10 years he functioned capably, serving as private secretary to Adm. Sir John Borlase Warren at St. Petersburg and accompanying expeditions to Spain and the Netherlands. By dint of good service, Bisshopp rose to brevet major in January 1812, and the following month he transferred to Canada as inspecting field officer of the Upper Canada militia. That distant region was considered a backwater compared to military theaters in Europe, and assignment there was most unwelcome to ambitious young officers. But Bisshopp muted his disappointment and shouldered his responsibilities dutifully, declaring, “Were it not for the extensive command I have and the quantity of business I have to do, I should hang myself.” When the War of 1812 against the United States commenced on June 18, 1812, the young soldier suddenly found himself with more than enough work to keep him occupied.

After passing several months at Montreal, Bisshopp was transferred to the Niagara frontier attached to British forces under Gen. Roger Hale Sheaffe. He was tasked with commanding regular and militia forces stationed between Chippewa and Fort Erie near the southernmost end of the Niagara Peninsula. On November 28, 1812, an American invasion force under Gen. Alexander Smyth had gathered at Black Rock, New York, for the purpose of crossing into Canada. To facilitate this invasion, an advanced party of several hundred men landed the previous night to spike the guns and destroy a bridge over Frenchman’s Creek. Bisshopp, however, successfully engaged the marauders in a confusing night battle and managed to drive them off with loss. Later that day, Smyth sent him an ultimatum demanding his surrender to “spare the effusion of blood,” but Bisshopp contemptuously declined. The American leader then suddenly and inexplicably ordered his force to disembark and return to their tents, much to the surprise and delight of the British defenders. Thus far, Smyth’s efforts at Niagara amounted to little and culminated in his removal.

In May 1813, the calm along the Niagara frontier was shattered by the American capture of Fort George at the northern end of the peninsula. Bisshopp, acting under the orders of Gen. John Vincent, abandoned Fort Erie to the enemy and rapidly withdrew his men to Burlington Heights. The Americans under Gen. John Chandler and William H. Winder mounted a slow pursuit, which was attacked in camp by Col. John Harvey at Stoney Creek on June 6, 1813. Bisshopp was present, commanding the reserves, but saw no fighting. Both Chandler and Winder were captured, and the leaderless invaders withdrew back to Fort George with British forces shadowing their every move. On June 25, American Gen. John Boyd dispatched a force under Lt. Col. Charles Boerstler, 14th U. S. Infantry, to burn a cache of British supplies at the DeCou House. En route, they were surrounded at Beaver Dams by a smaller force of Indians under Lt. James Fitzgibbon. Bisshopp at that time was stationed at Twelve Mile Creek with a strong picket, and he rushed two light companies of the 104th Foot and one from the Eighth to Fitzgibbon’s assistance. His prompt arrival at the height of the battle convinced Boerstler that he was both surrounded and outnumbered, so he capitulated his entire force. This disaster ended fighting in the vicinity of Fort George for the rest of the year and resulted in the resignation of Gen. Henry Dearborn.

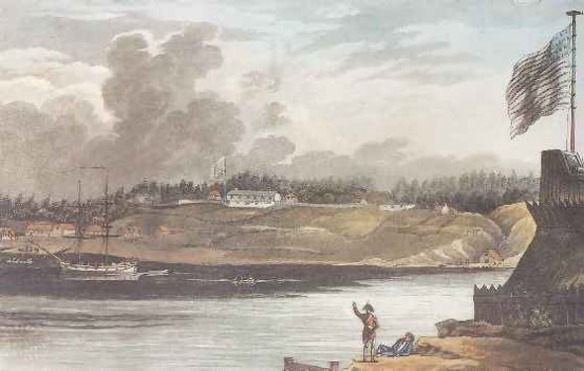

The British had thus far successfully contained various American forays, but their position was perpetually undermined by severe supply shortages, notably salt, which was essential for preserving meat. On July 11, 1813, Bisshopp became apprised of a great quantity of salt stored at Black Rock, across the Niagara River, and he resolved to launch a raid to acquire it. Early that morning he assembled 200 regulars and 44 Canadians under Fitzgibbon, then landed on the New York side unannounced. Surprise was complete, and the British very nearly captured Gen. Peter B. Porter of the militia, a former “war hawk” congressman who had helped precipitate the War of 1812. Clad only in his nightgown, Porter hastily mounted a horse and fled down the street while Bisshopp began supervising removal of salt, “a scarce and most valuable article.” His men also began burning various warehouses and the 50-ton schooner Zephyr anchored in the river. During these actions, however, Porter was actively rallying his dispersed militia for a counterattack. The Americans received timely and welcome assistance from a body of Seneca Indians under Farmer’s Brother and Young King, who attacked the British as they loaded booty onto their boats. Bisshopp managed to escape under a galling fire, but he was hit three times. Twenty-seven British soldiers were also killed or wounded.

Bisshopp lingered in great discomfort for several days before dying from his injuries on July 16, 1813. To his dying gasp he accepted full responsibility for his defeat and was visibly tormented over the loss of so many men. In light of his great popularity among British soldiers and Canadian militiamen, Bisshopp’s passing was lamented. He was a most valuable officer, brave, devoted to the well-being of his men, and preferred to serve his country than dine on riches and enjoy the inheritance awaiting him at home.

Bibliography Allen, Robert S., ed. “The Bisshopp Papers During the War of 1812.” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 61 (1983): 22-29; Babcock, Louis. The War of 1812 Along the Niagara Frontier. Buffalo, NY: Buffalo Historical Society, 1927; Chartrand, Rene. British Forces in North America, 1793-1815. London: Osprey, 1998; Green, Ernest. “Some Graves at Lundy’s Lane.” Niagara Historical Society Publications 22 (1911): 4-6; Suthren, Victor. The War of 1812. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1999; Turner, Wesley. The War of 1812: The War That Both Sides Won. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1990.