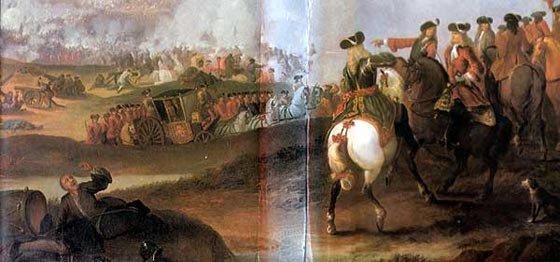

The Duke of Marlborough at the Battle of Ramillies, 1706

The Battle of Ramilies, 23 May 1706. The 16th Foot charging French infantry.

The year 1706 brought great success. Intent on avenging Blenheim, underestimating British strength, and concerned to push Marlborough back, Louis XIV ordered Villeroi to advance, but the consequences were disastrous for France. On a spread-out battlefield at Ramillies (23 May), Marlborough again obtained a victory by breaking the French centre after it had been weakened in order to support action on the flanks. Attacks on both flanks tied down much of the French army, including the infantry on their right. A cavalry battle on the French centre-right was finally won by the Allies and, as the French right wing retreated, the British, their preparations concealed by dead ground, attacked through the French centre, leading to the flight of their opponents. The French lost all their cannon and suffered about 19,000 casualties (including prisoners), compared to 3,600 Allied casualties. This was the only one of Marlborough’s major battles in which Eugene did not take part.

Thus, in a six-hour battle of roughly equal armies, Marlborough showed the characteristic features of his generalship. Cool and composed under fire, brave to the point of rashness, Marlborough was a master of the shape and the details of conflict. He kept control of his own forces and of the flow of the battle, and was able to move and commit his troops decisively at the most appropriate moment, moving troops from his right flank for the final breakthrough in the centre.

Ramillies indicated the value of destroying the opposing field army, especially early in the campaigning season. It was followed by the rapid fall of a number of positions including Ath, Antwerp, Bruges, Brussels, Dendermonde, Ghent, Louvain, Menin, Ostend and Oudenaarde: most offered little or no resistance, but it proved necessary to besiege Dendermonde, Ostend, Menin and Ath. The cohesion of Villeroi’s army was largely destroyed by the battle. The regional and municipal authorities and Spanish garrisons in much of the Spanish Netherlands hastened to surrender, and the French were only able to organize resistance in a few fortresses. Ostend fell on 6 July, after a short siege in which an Anglo-Dutch squadron had bombarded the defences, Menin on 22 August, Dendermonde on 5 September, despite the French drowning much of the surrounding countryside, and Ath on 4 October. The new French commander, Vendome, led a larger army, much of it transferred from the Rhine, but he was unwilling to attack Marlborough as he covered the sieges in the Spanish Netherlands. The capture of Ostend improved supply routes between Britain and her army in the Low Countries.

The following year (1707) was less successful, as a result of political differences, both in Britain and among the Allies. Furthermore, both the larger French force, under Vendome, and the Dutch were reluctant to provoke a battle. Vendome cautiously took the initiative and improved the French position in the Low Countries. In 1708, however, the French advanced boldly from their fortified positions, although their larger army suffered from a poorly co-ordinated divided command. The French regained Ghent and Bruges, but Marlborough crushed their attempt to reconquer the Spanish Netherlands when he and Eugene defeated Vendome’s army at Oudenaarde (11 July). After several hours fighting, during which both sides moved units into combat as they arrived on the battlefield and the French pressed the Allied right and right-centre very hard, the French position was nearly enveloped when Marlborough sent the cavalry on his left around the French right flank and into their rear, thus destroying his opponents’ cohesion. However, the French successfully retreated under cover of the approaching night. Vendome had been badly let down by his co-commander, Louis XIV’s eldest grandson, the haughty Duke of Burgundy, and the French lost, not only, like the Allies, about 7,000 killed and wounded, but also about 7,000 prisoners and, more worryingly, their confidence.

Several British leaders would have preferred to exploit the victory by a bold invasion of France, but Eugene and the Dutch favoured a more cautious policy. Oudenaarde was followed by the lengthy and, ultimately, successful siege of Lille, the most important French fortified position near the frontier. It was well fortified, ably defended by a large garrison under Marshal Boufflers, and there was the prospect of Vendome relieving the position. A poorly coordinated attack on too wide a front on 7 September, commanded by Eugene, left nearly 3,000 attackers dead or wounded. The Allies were only successful when they concentrated their artillery fire, making a number of large breaches, beat off French diversionary attacks, and prevented the French from cutting their supply lines, defeating one such attempt at Wijnendale on 28 September. The town surrendered on 23 October, and the siege of the citadel proved less costly. It finally capitulated on 19 December 1708, after a siege of 120 days that cost the besiegers 14,000 casualties.

Far from going into winter quarters, Marlborough then overran western Flanders and recaptured Ghent and Bruges. The French attempt to regain the initiative in a nearby region had thus been defeated, and Marlborough had sustained his reputation, and that of his army, for delivering victory and for successful siegecraft. However, Vendome’s replacement, Villars, plugged the gap in the French defences by constructing the Lines of Cambrin which blocked any advance south from Lille.

Marlborough’s reputation received a serious blow the following year. He first besieged and captured Tournai, another important frontier fortification, but one whose loss did not breach the French defences. Most of the campaigning season was taken up by the siege. Well garrisoned, Tournai did not surrender until forced to do so by a shortage of food on 3 September. Marlborough moved on to besiege Mons, and attacked a French army, under the able Villars, entrenched nearby at Malplaquet, a position chosen so as to threaten the siege and provoke a British attack on terrain suited to the defence. The battle, on 11 September 1709, exemplified Marlborough’s belief in the attack, but it also indicated the heavy casualties that could be caused by the sustained exchange of fire between nearby lines of closely packed troops.

As later with Frederick the Great and his Austrian opponents, Marlborough’s tactics had become stereotyped, allowing the French to prepare an effective response. They held his attacks on their flanks and retained a substantial reserve to meet his final central push by nearly 30,000 cavalry. The French finally retreated in the face of eventually successful pressure on their left and centre, but their army had not been routed and they were able to retreat in good order. The casualties were very heavy on both sides, including 24,000 (8,000 of them British) of the 110,000 strong Anglo-Dutch-German force, although only about 12,000 of their opponents; indeed, the battle was the bloodiest in Europe prior to that of Borodino during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. As before, Marlborough’s tactics were based on the acceptance of the likelihood of heavy casualties, but at Malplaquet these casualties did not serve to obtain mastery of the battlefield. The heavy casualties affected Marlborough, not only by increasing political criticism, but also by making him less ready to risk battle.

As with the battle of Sheriffmuir in 1715, it was the momentum of result that was crucial. Marlborough went on to capture Mons (20 October) and Ghent (30 December 1709), but hopes of breaching the French frontier defences and marching on Paris were misplaced. In particular, heavy casualties among their soldiers lessened Dutch support for the war.

In 1710 Marlborough showed his mastery of manoeuvre, penetrated the Lines of Cambrin, south of Lille, early in the campaigning season and then sought to enlarge the new gap in the French defensive system. He besieged and captured Douai (29 June), but then, instead of pressing south towards Paris, moved west along the French lines, besieging and capturing Béthune (29 August), Saint-Venant (30 September) and Aire (9 November). The siege of Douai, however, had taken longer than expected, and Villars then blocked Marlborough’s route towards Arras in a strong position.

The following year, Marlborough decided to press south, but Villars had strengthened the French defences with the 160 mile long Lines of Ne Plus Ultra (no further) which stretched from Etaples via Arras and Mauberge to Namur. Marlborough succeeded in misleading the defenders, crossed the lines without casualties near Arleux (5 August), and, in a well-conducted siege, besieged and captured Bouchain (12 September), a strongly-garrisoned fortress protected by marshes as well as fortifications.

Such achievements among the French frontier positions were no longer sufficient. Marlborough could no longer deliver a major victory, and Bouchain was too little to show for a year’s campaigning. In addition, support for a continuation of the costly war had eroded in Britain and the Tory government that came to power in 1710 both dismissed Marlborough (31 December 1711) and, in 1713, abandoned Austria in order to negotiate, by the Treaty of Utrecht, a unilateral peace with France. The previous year, Marlborough’s successor, the Tory Duke of Ormonde, under “restraining orders” that forbade him from taking part in a battle or siege, had failed to provide Eugene with support, and Eugene was defeated by Villars at Denain. Villars went on to recapture Douai and Bouchain.

By 1713 British military expenditure had fallen to a point where there were only about 23,500 subject troops. Under the Treaty of Utrecht, Louis regained Aire, Béthune, Lille and Saint-Venant. His fortification system, which had served him so well in the war, was largely restored, although he had to accept a number of permanent losses, including Tournai. Philip V was left in control of Spain, but “Charles III”, now the Emperor Charles VI, gained Lombardy, Sardinia and the Austrian Netherlands. Thus, the Bourbons had been kept out of the Low Countries.

Under Marlborough, the British army reached a peak of success that it was not to repeat in Europe for another century. The combat effectiveness of British units, especially the fire discipline and bayonet skill of the infantry, and the ability of the cavalry to mount successful charges relying on cold steel, owed much to their extensive experience of campaigning and battles in the 1690s and 1700s. These also played a vital role in training the officers and in accustoming the troops to immediate manoeuvre and execution. This was the most battle-experienced British army since those of the Civil War, and the latter did not take place in battles that were as extensive or sieges of positions that were as well fortified as those that faced Marlborough’s forces.

The cavalry composed about a quarter of the army. Like Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden in the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48), Marlborough made his cavalry act like a shock force, charging fast, rather than as mounted infantry relying on pistol firepower. He used a massed cavalry charge at the climax of Blenheim, Ramillies and Malplaquet. The infantry, drawn up in three ranks, were organized into three firings, ensuring that continuous fire was maintained. British infantry fire was more effective than French fire, so that the pressure of battlefield conflict with the British was high. The inaccuracy of muskets was countered by the proximity of the opposing lines, and their close-packed nature. The artillery were handled in a capable fashion: they were both well positioned on the field of battle, and were resited and moved forward to affect its development. As Marlborough was Master-General of the Ordnance as well as Captain-General of the Army, he was able to direct the artillery. His view of the need for co-operation led him to be instrumental in the creation of the Royal Regiment of Artillery in 1722; the first two artillery companies had been created at Gibraltar in 1716. However, the British lacked sufficient expertise to mount major sieges on their own and had to turn to Dutch engineers; they were not noted for their celerity.

Marlborough’s battles were fought on a more extended front than those of the 1690s, let alone the 1650s, and thus placed a premium on mobility, planning and the ability of commanders to respond rapidly to developments over a wide front and to integrate and influence what might otherwise have been in practice a number of separate conflicts. Marlborough was particularly good at this and anticipated Napoleon’s skilful and determined generalship in this respect. Marlborough was also successful in co-ordinating the deployment and use of infantry, cavalry and cannon on the battlefield. In strategy, he was more successful than other contemporary generals in surmounting the constraints created by the need to protect or capture fortresses: Marlborough turned an army and a system of operations developed for position warfare into a means to make war mobile.