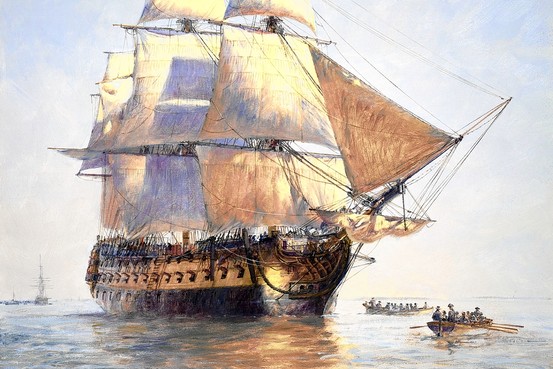

A contemporary depiction of the 98-gun HMS Temeraire by renowned marine artist Geoff Hunt. Geoff Hunt RSMA/Art Marine, UK.

The Temeraire started life in the ancient shipyard of Chatham in 1793, costing a staggering £73,241 (£4million today).

However, the inadequacies of Chatham were clearly demonstrated at this time. In September 1770, when a controversy arose over the frequently contested Falkland Islands, war with Spain was viewed as a distinct possibility. Orders were given for the fleet to be mobilised, with Chatham receiving instructions to prepare nine ships for Channel service. Despite the urgency, Chatham was quite unable to respond, with three of the dry docks already occupied while the fourth was out of use due to a long-term repair need to its own timberwork. Matters were further compounded by the absence of a masting hulk, a large vessel fitted with lifting gear and used to step into position the masts of warships being prepared for service. At that time, and serving as additional proof that facilities at Chatham needed considerable updating, the ageing Chatham mast hulk was itself occupying one of the dry docks, being also in considerable need of repair.

The ill-preparedness of Chatham at the time of the Falklands crisis was duplicated at the outset of the American War in 1775. Even before the actual declaration of hostilities, complaints were voiced that the dockyard was behind with work that had been allocated to it, a situation made worse by a shipwrights’ strike earlier in the year over the imposition of task work. With the situation in America rapidly deteriorating, the workload at Chatham increased. By the end of October warrants had been received from the Navy Board for the fitting out of eleven ships ‘for foreign service’, with three of the four dry docks allocated to this work. All seemed to be going reasonably well until the following summer. Upon examining the Old Single Dock in June 1776, a structure that had now seen 150 years of usage, extensive areas of wood rot were revealed. This had caused ‘the apron’, the ledge upon which the entrance gates rested, to start breaking up so that ‘the whole must be taken up, and piles drove to secure the groundways’. It was determined that this work must be immediately undertaken, with all available house carpenters transferred to the task and so delaying work due to have been undertaken on the thirty-two-gun Montreal.

With regard to Chatham’s important shipbuilding role, it was much easier to plan ahead, a sudden emergency less likely to impact upon plans that had often been agreed several years in advance. Indeed, those employed in building a particular vessel, in the event of a sudden fleet mobilisation could be moved from the construction of a new vessel to that of helping prepare a vessel that had been newly taken from the Ordinary. Most new construction work was undertaken on a building slip, this ensuring that all dry docks were available for the repairing and maintenance of ships as and when required. However, there were exceptions, with the larger first- and second-rate three-decked warships often being built in dry dock. Nelson’s flagship at Trafalgar, the 100-gun Victory, was one such example. She had been built in the Old Single Dock, having her keel first laid down in 1759 and eventually floated out in 1765. That she remained in dry dock for such a lengthy period underlines the problem of using the dry dock for new construction work, as it blocked use of this facility for the entire period of construction, including six months that was usually set aside for the vessel to season in frame. However, Victory’s long-term occupancy of the Old Single Dock was an exception, her period of seasoning having been extended by a change in the international situation. At the time she was laid down, the subsequently named Seven Years War (1756–63) was creating a considerable demand for such vessels and her construction was regarded as urgent. Following a series of stunning victories that took place in the same year as she was laid down, it was no longer felt necessary to complete her for immediate wartime service and for this reason she remained in dry dock for six years. In commemoration of those victories, the year 1759 became known as the Year of Victories, with the new first-rate under construction at Chatham taking her name from that particularly momentous year.

Three important documents relating to the construction of Victory are held at the National Maritime Museum and recently highlighted by the Chatham Historic Dockyard Society in their newsletter Chips. One relates to the naming of the ship and the other two to her successful launch. On 30 October 1760 the Navy Board informed the officers at Chatham dockyard:

The Right honourable the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty having directed us to cause the ships and sloops mentioned on the other side to be registered on the list of the Royal Navy by the names against each expressed; We direct you to cause them to be entered on your Books, and called by those names accordingly.

On the other side of the document were listed three ships that were then under construction at Chatham, these of 100, ninety and seventy-four guns and to be named respectively, Victory, London and Ramillies. As to the launch of Victory, the officers at Chatham received a further letter, this dated 30 April 1765:

The Master Shipwright having acquainted us that His Majesty’s Ship Victory building in the Old Single Dock will be ready to launch the ensuing Spring Tides. These are to direct and require you to cause her to be launched at that time accordingly if she is in all respects ready for it.

Confirming that this was carried out according to those instructions, Commissioner Hanway wrote to both the Navy Board and Admiralty informing them that Victory had been floated out of the Old Single Dock on 7 May, with this reply received from Philip Stephens, Secretary to the Board of Admiralty:

I have communicated to My Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty your letter of the 6 & 7 inst. the former giving an Account of the Augusta being put out of the Dock, the latter of the Victory being safely launched yesterday.

Following her launch (or floating out), Victory spent the next thirteen years in the Ordinary, there being no particular need for a ship of her size during the years of peace that had followed the ending of the Seven Years War and the immediate opening years of the American War of Independence. It was not, therefore, until 1778 that she left the Medway, going on to serve in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. Following a further period in the Chatham Ordinary, she was called upon to serve in 1793 upon the outbreak of war with Revolutionary France. A further return to Chatham saw Victory entering dry dock in 1800 for what was termed a ‘middling’ repair. On inspection it was found that far more work would have to be carried out than had initially been anticipated. The ‘middling’ repair subsequently became a rebuild, at a cost of £70,933, with much of the hull and stern replaced, rigging and masts renewed and modifications made to the bulwark. Undocked on 11 April 1803, she was immediately ordered to Spithead where she was to wear the flag of Admiral Nelson. Still flying his flag, she went on to gain immortal fame in October 1805 when she, with Temeraire immediately to her stern, led the British fleet at Trafalgar.