While the Allies had made a decisive move against Nazi Germany with the launching of Operation Overlord on 6 June, the Japanese High Command still awaited the next major American move in the Pacific, uncertain where it would actually fall but confident that once it had begun it would be repelled with devastating force somewhere within the `Great Triangle’. When one is convinced that something is bound to happen and it doesn’t, the concept of inevitability is undermined and the element of surprise takes a greater toll than it might otherwise have done. Japanese conviction that the next American attack would be in the Southwest Pacific had hardened over time and had assumed the official orthodoxy within the Gunreibu. When a reconnaissance flight on 10 June revealed that the Majuro atoll used by some of the US carrier groups was empty, Vice-Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, in command of the First Mobile Fleet, responded by sending the two largest battleships ever built, Musashi and Yamato, southwards from Tawi Tawi towards Biak and the northern coast of New Guinea to see what was going on. Something was obviously afoot, but without any signals or any other intelligence to go on, locating the American fleet was a far from straight forward task. Ozawa knew that only after the American carriers had been spotted could the Japanese activate Operation A-Go- in a bid to trap them on their push southwestwards. One can imagine the sense of unease in these IJN circles, therefore, when the news that arrived in the Philippines and Japan next day did not put the American carrier force on such a route at all but 1000nm (1,852km) away in the Central Pacific carrying out raids on the islands of Guam, Saipan and Tinian in the Marianas chain.

Caught unawares, both Toyoda and Ozawa wondered what on earth it could possibly mean. Was this merely a softening up before a major strike or was it a classic piece of strategic deception – a diversion to hide a movement elsewhere in a widely divorced theatre of operations? Since neither man knew for certain, they waited for confirmation of whether it was one thing or the other. Further carrier raids on all three islands on 12 and 13 June were sufficient to convince Ozawa at least that the Americans had opted to avoid targets within the `Great Triangle’ at this stage in favour of those in the Marianas. He issued an order to the warships under his command at 1727 hours on 13 June requiring them to prepare themselves for the commencement of Operation A-Go-. This meant abandoning their deployment in the Philippines and gearing up for a decisive battle to the northeast.

In a savage twist of irony, the Americans had chosen to invade the very same island – Saipan – on which Vice-Admiral Takagi had recently established the Japanese Submarine Sixth Fleet Headquarters. Takagi, like many of his peers, had thought that Palau was likely to be chosen by the Americans as the site for their next major incursion and so he had had no qualms whatsoever in moving to Saipan and using the port of Garapan as the most appropriate base for his own Advance Expeditionary Force. It was another ghastly mistake that would undermine any chance he would have of directing submarine operations in the region. It would end up with him and his staff hiding in the mountains of Saipan awaiting rescue rather than plotting some counter-attack against the shipping involved in Forager or the American carrier force that would be pitted against Ozawa’s fleet in the Philippine Sea. Unable to be rescued, Takagi decided that it was better to die in combat than to be made a POW and with a final signal to Toyoda on 6 July he charged the American lines in a hopeless Banzai attack. While Takagi’s fate didn’t mirror that of his submarine force, there was a certain symbolism to it. Poorly positioned in any case, the submarines adopted picket lines that could be detected and effectively dealt with by enemy warships that were employing a markedly improved set of ASW techniques developed as the war had progressed. Subject to rather haphazard and uncoordinated sets of orders which did them no favours, the submarines found survival difficult. By the time Saipan fell on 9 July nine of the twenty-one submarines around the Marianas at the time of Forager had been sunk and four more would be destroyed before the end of the month.

After the initial softening up of Guam, Saipan and Tinian from 11 June, Forager began in earnest three days later with a more sustained bombardment of Saipan. Spruance had given Kelly Turner’s TF 52 a solid core of warships amounting to seven battleships, eight escort carriers, eleven cruisers and no less than thirty-seven destroyers to pound the Japanese defences remorselessly from both offshore and overhead throughout 14 June and set the tone for the first assault wave that would come ashore on the following morning. Assisted by these warships, two transport groups brought thirty-four attack and supply transports with two Marine divisions and four LSDs (Landing Ship Docks) onto the beaches of Saipan beginning at 0844 hours on 15 June and these were followed by many more landing craft and other vessels in the following days. In all Turner was responsible for the safety of 551 ships in this operation. It seems extraordinary that he lost none to either submarine or aircraft attacks in the initial and subsequent landings on the island. What seems incomprehensible becomes more readily understandable if one accepts that there was a marked shortfall both in the number of operational aircraft that had survived Mitcher’s carrier raids over the Marianas and in trained pilots capable of flying them. Many of the latter had been lost in combat and illness had also hit many of the rest hard as well. As a result, TF 52 succeeded in putting 67,451 troops ashore under the command of General Holland M. Smith and into an uncompromising three-and- a-half-week battle with Lt. General Yoshitsuyu Saito’s infantry troops and Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s naval forces who exploited both the terrain and the gap between the two American forces superbly. It was a measure of the intensity of the action on Saipan that only 1,780 Japanese troops were taken prisoner out of a force of 25,591 – the rest being killed in the campaign that also took the lives of 3,426 American servicemen and injured another 13,099 Marines by the time the island was taken on 9 July. Nagumo committed suicide three days earlier when it was clear that the Japanese were going to be defeated.

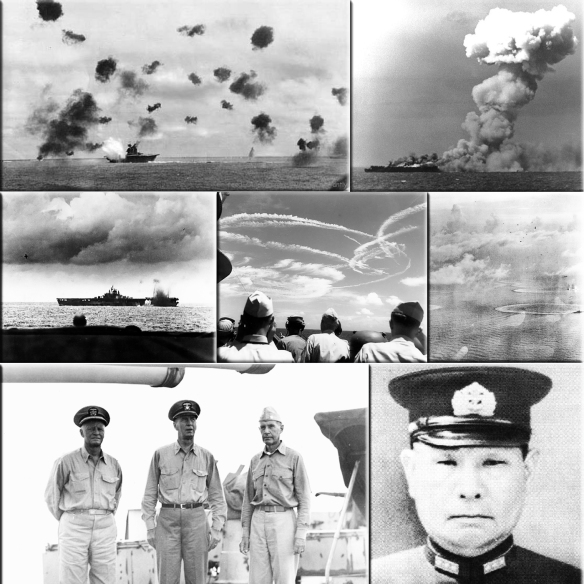

Receiving news of the first landings on Saipan, Admiral Toyoda wasted no time in ordering the Combined Fleet to activate Operation A-Go- and seek the decisive battle with the Americans. Shortly afterwards, at 0900 hours he repeated the signal that his illustrious predecessor, Admiral Togo, had used before the Battle of Tsushima Strait in May 1905: `The rise and fall of Imperial Japan depends on this one battle. Every man shall do his utmost.’ When battle was joined four days later, however, the same dashing success that Togo had achieved against the Russians some thirty-nine years before would not be savoured by Ozawa. In truth, the parallels between the decrepit fleet that Togo faced and the formidable striking force that Ozawa would line up against on 19 June – Marc Mitscher’s TF 58 – were utterly misplaced. TF 58 consisted of seven fleet carriers, eight light carriers, seven battleships, eight heavy cruisers, thirteen light cruisers and fifty-nine destroyers. It also possessed twice as many carrier aircraft as that under Ozawa’s command (over 900 to the 450 the Japanese carried with them) and in the Hellcat the Americans had a faster, if less manoeuvrable but far better armed and protected, air frame than the Zero it was up against. If that wasn’t sufficient an advantage, the American fighter pilots were generally more experienced than their Japanese counterparts, while the skill level of their bomber pilots also exceeded that of their opponents who had lost so many of their first-rate pilots in the war. They were now forced to rely upon those who couldn’t really make the most of their demanding Yokusuka Suisei dive-bomber (known by the Allies as a `Judy’) and the Nakajima Tenzan torpedo-bomber (referred to by the Americans as a `Jill’). Against this concentrated mass of firepower, Ozawa divided his own forces into three main groups. In the Vanguard and under Vice-Admiral Takeo Kurita’s command were three light carriers, four battleships, four heavy cruisers and eight destroyers led by the light cruiser Noshiro. In the main body of the fleet, Carrier Group A, Ozawa was to be found in his flagship the fleet carrier Taiho, with two other carriers (Shokaku and Zuikaku), veterans of earlier naval battles, in attendance. Rounding out the group were a couple of heavy cruisers and six destroyers led by the light cruiser Yahagi. In Carrier Group B Rear-Admiral Takaji Joshima had the two converted carriers Hiyo- and Junyo, the old training carrier Ryuho, the battleship Nagato, the heavy cruiser Mogami, along with seven destroyers. Supporting the entire fleet were a total of six tankers including the Hayasui, which was designed as a modern fleet tanker with seaplane carrier potential, and six destroyer escorts formed into two uneven groups. While some of Ozawa’s warships, most notably his own flagship, were fine vessels, the aggregate sum of the individual parts was simply not the match of Mitscher’s TF 58 either in terms of quantity or quality.

While the Japanese were still capable of doing massive damage with their carrier aircraft, Spruance, the Commander of the 5th Fleet, and Mitscher, his Task Force commander, flying their flags in the Indianapolis and the Lexington respectively, held the whip hand not least because they were the beneficiaries of a sophisticated and integrated system of fighter control that far exceeded anything their enemy possessed. From the outstandingly effective `SC’ and `SK’ radars that could pick up objects at anything from 60 to 100nm (85 to 111km), height information would be supplied from `SM’ radars, and surface approach radars (`SG’ and `Mk1 Eyeball’) could detect low-level attack formations. All of this information was relayed to Combat Information Centers where enemy raids were plotted and the details passed on to a Fighter Direction Officer (FDO) at the heart of the task force and to others who were present in each one of the five task groups of TF 58. This enabled the task force to operate either as a coordinated whole or as a set of independent groups depending upon the situation it faced. Armed with this crucial information, the FDOs could vector in their combat air patrols to intercept the enemy planes many miles away from the American carriers. It was a superbly efficient system built upon technology that rarely let them down and an experienced staff who knew what they were supposed to do and did it repeatedly.

Spruance knew from the submarine reports he had been receiving from 15 June onwards that Ozawa was on the move. Being the cautious man he was and not wanting to be duped by his opposite number, Spruance opted to keep TF 58 positioned west of Tinian so as to ensure that his ships would straddle Ozawa’s path and prevent him from falling upon TF 52 and the troops Turner’s ships had disgorged onto Saipan. Although he had received a report from the submarine Cavalla just before 0400 hours on the 18th confirming that she had found fifteen vessels of Ozawa’s 1st Mobile Fleet some 800nm (1,482km) WSW of Saipan at midnight. Spruance wondered whether it was some kind of decoy force set up to lure him away from the Marianas while the rest of the main fleet, lurking elsewhere, would strike at the denuded invasion fleet. As a result, he didn’t approve Mitscher’s request that he should immediately set off in hot pursuit of the enemy in the hope of closing the Japanese position before nightfall. Mitscher thought that if his planes found Ozawa they would also find Kurita in close attendance. His plan was typically aggressive and rested on the possibility of launching a carrier attack in the late afternoon or early evening. Neither Spruance nor Lee wished to quit the waters off Saipan for a high speed chase after a dubious quarry and both were far from enthusiastic about engaging in a confrontation in the dark with an enemy who had mastered the tactics of night fighting. Mitscher (known throughout the USN as `Bald Eagle’) and his fellow aviators were grievously disappointed with Spruance’s `safety first’ tactics. Spruance opted on this occasion for caution and consolidation over risk. He thought the Japanese were capable of duplicitous action and didn’t wish to fall into a trap of their making. Consequently, he waited for further confirmation of where the enemy was before planning his next move.

Mariana Islands Campaign and the Great Turkey Shoot Timeline

11 May 1944 Japanese Navy devised Operation A-Go for the defense of the Mariana Islands; it would be launched in Jun 1944.

15 Jun 1944 American troops invaded Saipan, Mariana Islands.

16 Jun 1944 US submarines detected two large Japanese fleets near the Philippine Islands, headed towards the Mariana Islands.

19 Jun 1944 US carrier aircraft won a decisive victory over their Japanese counterparts in the Mariana Islands, shooting down over 200 planes with only 20 losses in what became known as the Marianas Turkey Shoot, or, officially, Battle of the Philippine Sea.

14 Jul 1944 In the Mariana Islands, US Seventh Air Force P-47 Thunderbolt fighters based on Saipan again struck Tinian Island. At Guam, US battleships joined in on the pre-invasion bombardment while transport USS Dickerson delivered US Navy underwater demolition specialists to survey landing beaches on the island.

15 Jul 1944 In the Mariana Islands, US Seventh Air Force P-47 fighters based on Saipan attacked targets on Tinian.

16 Jul 1944 In the Mariana Islands, P-47 Thunderbolt aircraft of US Seventh Air Force from Saipan attacked Japanese targets at Tinian. At Merizo, Guam, Japanese Army troops massacred 30 civilians.

17 Jul 1944 US Navy underwater demolition teams began destroying beach obstacles at Guam, Mariana Islands.

18 Jul 1944 In the Mariana Islands, American P-47 fighters based on Saipan attacked Japanese positions on Tinian and Pagan.

19 Jul 1944 In the Mariana Islands, US 7th Air Force launched P-47 aircraft based on Saipan to attack Tinian.

20 Jul 1944 P-47 aircraft of US 7th Air Force continued to attack Japanese positions on Tinian while US Navy warships bombarded Guam in the Mariana Islands. Meanwhile, underwater demolition teams conducted their final missions to remove obstacles on the invasion beaches at Asan and Agat on Guam.

21 Jul 1944 US 3rd Marine Division landed near Agana and US 1st Provisional Marine Brigade landed near Agat on Guam, Mariana Islands; the landing was supported by US Navy Task Force 53. US Navy and US Army aircraft attacked Tinian of Mariana Islands, Eniwetok of Marshall Islands, and Truk and Yap of Caroline Islands as indirect support. Troops of the US Army 77th Infantry Division arrived in the afternoon; their landing was difficult due to the lack of LVT vehicles. A mile-deep beachhead was established at both landing sites by sundown. The Japanese attempted a counterattack during the night, which was repulsed.

24 Jul 1944 American troops landed on Tinian, Mariana Islands.

28 Jul 1944 US Marines captured the old US Marines parade ground on Guam, Mariana Islands.

10 Aug 1944 US forces declared Guam, Mariana Islands secured.

24 Jan 1972 Japanese Army Sergeant Shoichi Yokoi was discovered in the mountains by residents of Guam, Mariana Islands, who refused to believe that Japan had lost the war 26 years prior.