Napoleon did not yet dominate the European world as he would as Emperor of the French after May 1804. He was not yet even First Consul, which he would be appointed in December 1799. He already promised to become, however, the leading political figure of the French Republic and was unquestionably its outstanding general, at a moment when French armies dominated Europe. The First Coalition of enemies of the French Revolution, formed in 1792 by Austria and Prussia, later joined by the north Italian Kingdom of Sardinia, and enlarged by the French declaration of war on Spain, the Dutch Netherlands and Britain, had progressively fallen to pieces during the 1790s. The Netherlands had been occupied in early 1795 and reorganised as the Batavian Republic, under French control. Prussia and Spain had made peace later that year; in August 1796, under French pressure, Spain actually declared war on Britain, closing its ports in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean to the Royal Navy and adding the strength of its large fleet to that of the French.

In 1796 the young General Bonaparte confirmed his growing reputation with a series of spectacular victories in northern Italy. After defeat at the Battle of Lodi in May, the King of Sardinia made peace and ceded the port of Nice and the province of Savoy to France. During the rest of the year, Bonaparte harried the armies of the Austrian empire out of its north Italian possessions by inflicting defeats at Castiglione and Arcola. Finally, after weeks of manoeuvring around the fortress of Mantua, Bonaparte won a crushing victory at Rivoli on 14 January 1797 and drove the defeated Austrians back into southern Austria. The Austrian emperor sued for peace, concluded at Campo Formio in October. The terms included the creation of a puppet French Cisalpine Republic in northern Italy and the cession of the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium) to France. In February 1798 the French occupied Rome and made the Pope prisoner; in April France occupied Switzerland.

The outcome of this succession of conquests was to leave Britain, which refused to make peace, without any ally except tiny Portugal, and without bases, except for the Portuguese Atlantic ports, anywhere in mainland Europe. Russia, the only powerful continental state still resistant to French influence, was keeping its counsel. Turkey, ruler of the Balkans, Greece and the Greek islands and Syria, and nominal overlord of Egypt and the pirate principalities of Tunis and Algiers, remained a French ally. The old maritime Republic of Venice had been given to Austria at the Treaty of Campo Formio but would soon pass to France. The foreign policy of the Scandinavian kingdoms, Denmark and Sweden, was subservient to that of France. As a result, not a mile of north European or southern Mediterranean coastline – except for that of the weak Kingdom of Naples, Portugal and the island of Malta – lay outside French control. The Baltic was effectively closed to the British, so were the Channel and Atlantic ports, so were the Mediterranean harbours. All Britain’s traditional overseas bases, except for Gibraltar, had been lost. In October 1796 the British government felt compelled to withdraw its fleet from the Mediterranean, where it had maintained an almost continuous presence since the middle of the seventeenth century, and to concentrate the navy in home waters. England was actually threatened by invasion; had it not been for Admiral Jervis’ defeat of the Spanish in the Atlantic off Cape St Vincent in February 1797 and Admiral Duncan’s destruction of the Dutch fleet at the Battle of Camperdown in October, her enemies might have achieved a sufficient combination of force to fulfil the necessary conditions for a Channel crossing.

Despite the reduction in the enemy’s naval strength the two victories brought about, the Royal Navy could not rest confident of its ability to contain the threat; in October 1798 Bonaparte was appointed to command an ‘Army of England’, organised to sustain the pressure. Moreover, Britain correctly sought to pursue an offensive strategy, directed at checking invasion by forcing France to look to the protection of its own interests, rather than waiting passively to respond to French attacks. That required the maintenance of several separate concentrations of strength, a Channel fleet to defend the short sea crossing, an Atlantic fleet to blockade the great French bases at Brest and Rochefort and to keep an eye on the remains of the Spanish navy in Cadiz, detached squadrons to protect the British possessions in the West Indies, at the Cape of Good Hope and in India, and a host of smaller line-of-battle ships and frigates to protect the convoys of merchantmen and Indiamen on which British trade, the lever of the war against France, depended.

Britain had the superiority. In 1797 it had 161 line-of-battle ships and 209 fourth-rates and frigates, against only 30 French line-of-battle ships and 50 Spanish.3 The French and Spanish did not, however, have to keep the seas, but could remain comfortably in port, awaiting their chance to sally forth at an unguarded moment, while the British ships were constantly on blockade, wearing out their masts and timbers in a battle with the elements, or else in dockyard, repairing the damage. Only two-thirds of the Royal Navy was on station at any one time, while the demands of blockade and convoy even further reduced the numbers available to form a fighting fleet for a particular mission: Duncan had only 16 ships to the Dutch 15 at Camperdown, Jervis was actually heavily outnumbered, 15 to 27, at Cape St Vincent. Moreover, both the French and Spanish navies built new ships at a prodigious rate and found less difficulty in manning than the British did. With larger resources of manpower, they conscripted soldiers and landsmen to fill the naval ranks and, while the recruits included fewer experienced seamen than the British collared by the press, they were not necessarily more unwilling. The inequity of the press, the paucity of naval pay, the harshness of life aboard, caused large-scale naval strikes in the Royal Navy in the spring of 1797 – the ‘mutinies’ at Spithead and the Nore – which, for once, frightened the admirals out of thinking flogging the cure for all indiscipline. The prospect of joining action against the revolutionary French with an untrustworthy lower deck prompted immediate improvements to the lot of the common sailor.

Just in time. By the spring of 1798, a new naval threat had arisen. Unknown to the British government, the French leadership – the Directory – had relinquished for the time being the project of an invasion of England and decided to create an alternative threat to its island enemy’s strategic interests. The initiative had come from General Bonaparte. On 23 February he wrote, ‘To perform a descent on England without being master of the seas is a very daring operation and very difficult to put into effect . . . For such an operation we would need the long nights of winter. After the month of April, it would be increasingly impossible.’ As an alternative, he proposed an attack on King George III’s personal homeland, the Electorate of Hanover. Its occupation would not, however, damage the commercial power of Britain. He saw another possibility: ‘We could well make an expedition to the Levant which would menace the commerce of the Indies.’ The Levant, the region of the sunrise, lay across the shores of the eastern Mediterranean, in southern Turkey, Syria but also Egypt. Egypt was not only a fabled land but also the point at which the Mediterranean most nearly approached the Red Sea, the European means of access to the Indian Ocean and the Moghul dominions in India proper. France had not abandoned hopes of supplanting Britain as the dominant external influence in the Moghuls’ affairs, set back though its interests had been by British victories in the sub-continent in the last thirty years. A French descent on India, principal source of British overseas wealth since its loss of the American colonies, might deal a disabling blow to the Revolution’s chief enemy.

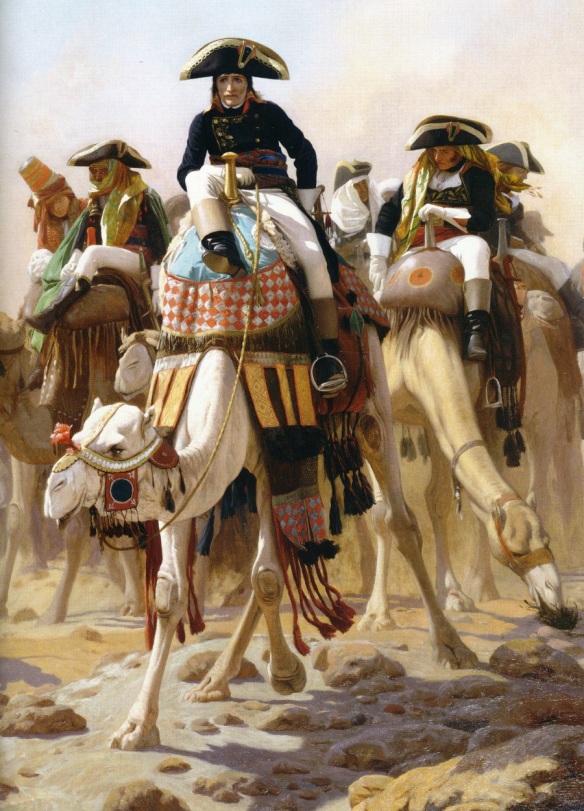

Bonaparte, moreover, had chosen the moment shrewdly. The Mediterranean was temporarily a French lake. Even given the diminished strength of its navy, enough warships could be found to escort a troop convoy from France’s southern ports to the Nile in safety, while its mercantile fleet, together with those of Spain and northern Italy, would provide transports aplenty. The withdrawal of the necessary force would not significantly deplete that required to sustain dominance over the defeated Austrians or to deter Russia from intervention in Western Europe. Moreover, an expedition would not be effectively opposed. Though Egypt was legally part of the Ottoman empire, under a Turkish governor, there was no proper Turkish garrison in the country. Power rested, as it had done since the thirteenth century, with the Mamelukes, a corporation of nominal slaves, purchased on the borders of Central Asia and trained as cavalrymen, who had usurped authority and used it to perpetuate their privileges. Though fiercely brave, they numbered only 10,000 and their ritualised horsemanship was tactically anomalous on a gunpowder battlefield. The local infantry they commanded was a half-hearted force.

Bonaparte found little difficulty, therefore, in persuading the French Foreign Minister, Charles de Talleyrand, that an Egyptian expedition was the next military step the Republic should take. Talleyrand enumerated the advantages, which included, surprisingly in view of the long-established Franco-Turkish entente,‘just reprisal for the wrongs done us’ by the Sultan’s government but also, more practically, ‘that it will be easy’, that it would be cheap and that ‘it presents innumerable advantages’.5 The five Directors argued against, more or less forcefully, but were worn down one by one. On 5 March 1798, they gave their formal assent to the operation.

Preparations then proceeded apace. Toulon was nominated the port of concentration; it was base to the thirteen warships – nine of 74 guns, three of 80, one (l’Orient) of 120 – which would form the escort and battle fleet. An order stopping the movement of merchant shipping out of Toulon and neighbouring ports quickly permitted the requisitioning of enough transports, half French, the rest Spanish and Italian, to embark the army. Fewer would have been preferable, for such a large number made a conspicuous presence, but contemporary Mediterranean merchantmen were too small to carry more than 200 men each. Some were also needed to carry horses, guns and stores. As a convoy keeping strict station a cable’s length (200 yards) apart, transports would occupy a square mile of sea. In practice, the varied quality of the vessels and their masters’ seamanship guaranteed straggling over a much wider area.

The Army of the Orient eventually numbered 31,000 men: 25,000 infantry, 3,200 gunners and engineers, 2,800 cavalry. Only 1,230 horses were embarked, however, Bonaparte believing that he could commandeer sufficient extra mounts in Egypt to supply the deficiency in charger and draught teams. It was a prudent decision. Horses were difficult to load, difficult to stable aboard and, however carefully tended, all too ready to die at sea. Their fodder also occupied a disproportionate amount of the cargo space, in which room had to be found for two months’ food for the troops. Correctly, Bonaparte, or more probably Berthier, the future marshal who was already his trusted chief of staff, doubted the ready availability of rations in Egypt. The army was organised into five divisions, among whose officers was another future Marshal of the Empire, General Lannes. The officers of the fleet, commanded by Admiral Baraguey d’Hilliers, included Admiral Ganteaume, who would lead Nelson a dance in the months before Trafalgar, and Admiral Villeneuve, his tragic opponent in that battle. L’Orient, the flagship, was commanded by Captain Casabianca, father of the boy who would stand on the burning deck at the coming encounter of the Nile.