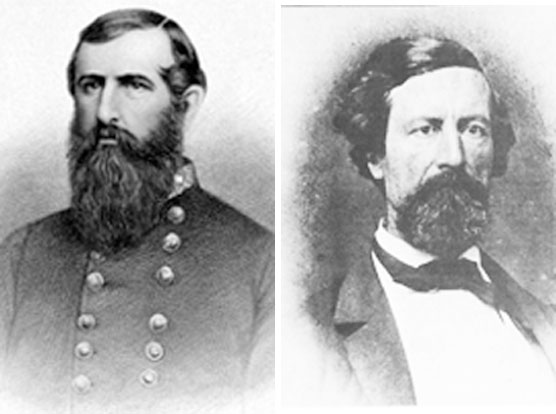

(August 10, 1814-July 13, 1881) Confederate General

Despite his Northern roots, Pemberton became a high-ranking Confederate military officer. He served capably and diligently but could not defend the all-important river city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. He ended up being a pariah in the North and South alike.

John Clifford Pemberton was born in Philadelphia on August 10, 1814. His father was personally acquainted with President Andrew Jackson, who helped the young man secure an appointment to the U. S. Military Academy in 1833. Pemberton graduated four years later midway in his class of 50 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Fourth U. S. Artillery. He served in Florida’s Second Seminole War until 1839 before commencing a wide-ranging tour of garrison duty. Following the onset of the Mexican-American War in 1846, he joined Gen. Zachary Taylor’s Army of Occupation in Texas and fought well at the Battles of Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, and Monterrey. His good service landed him a position as an aide-de-camp to Gen. William Jenkins Worth. The following year he transferred with Worth to Gen. Winfield Scott’s army in the drive toward Mexico City, winning additional praise for his performance at Churubusco, Molino del Rey, and Chapultepec. Pemberton received two brevet promotions to captain and major for bravery in battle, and citizens of his native Philadelphia voted him an elaborate sword. A turning point in his life occurred while he was serving at Fortress Monroe, Virginia, in 1848, when he met and married Martha Thompson, the daughter of a Southern shipping magnate. Over the next 12 years he continued acquitting himself well at various posts along the western frontier, receiving high marks as an administrator and rising to captain in 1850. In 1858, he marched with Col. Albert S. Johnston from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to Utah as part of the Mormon Expedition. He was serving at Fort Ridgley, Minnesota, in the spring of 1861 when the tide of Southern secession precipitated the Civil War.

Pemberton favored neither slavery nor secession, but he was a strong advocate of states’ rights. That stance, coupled with his wife’s ardent sectionalism, convinced him to resign his commission in April 1861 and fight for the Confederacy. This decision was roundly condemned by Pemberton’s family back in Philadelphia, and two of his brothers subsequently served in the Union folk and the James River. That November he transferred south to the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, to serve under Gen. Robert E. Lee. A skilled engineer, Pemberton labored long and hard with limited resources to improve the security of Charleston Harbor. He was responsible for the construction of Fort Wagner, which later proved invaluable to the defenses of the city. However, Pemberton also undermined his usefulness by declaring, from an engineering standpoint, that Fort Sumter was hopelessly obsolete and might as well be abandoned. That bastion, enshrined in Confederate annals as the starting point of the war, carried great emotional attachment, and the general was assailed in the press for his lack of respect. Worse, Pemberton also declared that if it were up to him he would abandon his department entirely rather than let his small army be captured by the enemy. The very notion of yielding an inch of Southern soil without fighting further alienated public sentiment against him. Pemberton was also rebuked by General Lee for his impolitic remarks, at which point President Jefferson Davis removed him from so sensitive a posting.

Pemberton may have been unpopular, and many Southerners continued viewing his Northern origins with suspicion, but Davis acknowledged his military value to the Confederacy. In October 1862, he arranged Pemberton’s transfer to the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana with the rank of lieutenant general. His overriding mission was to keep the Confederate bastion of Vicksburg, astride the Mississippi River, from falling into enemy hands. This was strategically essential for two reasons. First, from its position high on a cliff overlooking the river, Vicksburg’s cannons prevented Northern vessels from reaching either New Orleans or Memphis. It thus functioned as an immovable obstacle to Union generals trying to shift forces along the western theater. Second, with the recent capture of both those cities by Union forces, Vicksburg was the last remaining rail link to Richmond. As a railhead it was the sole communications junction with Texas, Arkansas, and western Louisiana. Vicksburg’s fall would literally cut the Confederacy in two and hasten its demise.

Pemberton arrived at the city in November and took immediate steps to strengthen its already formidable defenses. That month he dispatched Gen. William W. Loring to a bend in the Tallahatchie River to construct Fort Pemberton. The following March, “Old Blizzards” was instrumental in repelling a Union movement down that waterway. In December 1862, Pemberton dispatched cavalry under Nathan Bedford Forrest and Earl Van Dorn, who ravaged Union communications and supply lines at Holly Springs. The losses incurred there forced Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to postpone an overland march upon Vicksburg for several weeks. That same month, Union forces under Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman advanced against the north-side defenses of the city but were badly repulsed at Chickasaw Bayou. Over the next few months, Pemberton skillfully deployed his forces and thwarted every move by Grant to advance upon Vicksburg in force. It appeared that the Confederates, after months of bloody reverses in the West, would finally prevail.

In April 1863, Grant commenced his Big Black River campaign, arguably one of the most brilliantly fought offensives in all military history. He secretly marched his army down the western bank of the Mississippi River below Vicksburg while directing a gunboat flotilla under Cmdr. David Dixon Porter to run past the city’s defenses at night. This was successfully accomplished, as was a major cavalry raid deep inside Mississippi by Col. Benjamin H. Grierson. With Pemberton’s attention directed elsewhere, Grant then boarded Porter’s gunboats and landed on the eastern bank of the river several miles below Vicksburg. Moving inland with 41,000 men, he quickly drove Gen. Joseph E. Johnston out of Jackson, the state capital, severing the Vicksburg rail link. Pemberton, who had been ordered to assist Johnston, also sortied from the city and engaged Grant at Champion Hills and Big Black River on May 16 and 17. The Confederates were totally defeated and driven back into Vicksburg’s fortifications. Johnston repeatedly ordered Pemberton to abandon the city, lest he become trapped within its works, but President Davis countermanded him to remain and fight to the last. Before Pemberton had a chance to sort through these conflicting orders, Grant surrounded the city and commenced a formal siege. In the course of 46 days, Pemberton’s pent-up forces bloodily repulsed two determined Union attempts to storm the works. Grant then sat back and calmly let the defenders run out of supplies. By July 4, the garrison had all but been starved; with no chance of being reinforced by Johnston, Pemberton surrendered mighty Vicksburg, 30,000 men, and 600 cannons to Grant. In accordance with the surrender terms, Pemberton was paroled and released. This debacle, coming on the heels of Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg the previous day, was a critical point in the course of military events. With the Mississippi River now firmly in Union hands, a corner had been turned, and the Confederacy began its slow descent into ruin. As Abraham Lincoln’s eloquently declared, “The Father of Waters now flows unvexed to the sea.”

Pemberton had performed well, considering the odds, but his failure to defend the last Confederate bastion in the West made him an object of public loathing. His standing as an outcast was reinforced by General Johnston’s public accusations that he disobeyed orders and was directly responsible for the disaster. Worse still, his demonstrated talent for administration could have been valuable elsewhere, but the political climate throughout the South made such an appointment impossible. After waiting eight months without an assignment, Pemberton tendered his resignation and asked to be appointed a lieutenant colonel of artillery somewhere. His request was granted, and he demonstrated his loyalty to the South by spending the next year and a half as inspector of ordnance in Richmond. In the spring of 1865, he was reunited with Johnston in North Carolina, where he surrendered.

After the war, Pemberton settled down on a farm in Fauquier County, Virginia, where he farmed for several years. In 1876, he relocated with his family back to Philadelphia. He died in nearby Penllyn on July 13, 1881, a talented leader but, by circumstance, one of the most vilified figures of Confederate military history.

Bibliography Ballard, Michael B. Pemberton: The General Who Lost Vicksburg. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1991; Gallagher, Gary W. Lee and His Generals in War and Memory. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998; Grabau, Warren E. Ninety- Nine Days: A Geographer’s Views of the Vicksburg Campaign. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000; Howell, H. Grady. Hill of Death: The Battle of Champion Hill. Madison, MS: Chicasaw Bayou Press, 1993; Stanberry, Jim. “A Failure of Command: The Confederate Loss of Vickburg.” Civil War Regiments 2, no. 1 (1992): 36-68; Winschel, Terrance J. Vicksburg: Fall of the Confederate Gibralter. Abilene, TX: McWhiney Foundation Press, 1999; Woodworth, Steven E. Civil War Generals in Defeat. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1999; Woodworth, Steven E. Jefferson Davis and His Generals: The Failure of Confederate Command in the West. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990; Woodworth, Steven E. No Band of Brothers: Problems of Rebel High Command. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999.