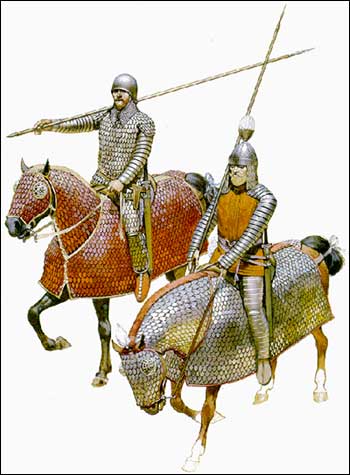

Parthian Cataphracts (Fully Armoured Parthian Cavalry)

Left: East Parthian Cataphract; Middle: Parthian Horse-Archer; Right: Parthian Cataphract from Hatra

Osroes I was one of the sons born to Vonones II by a Greek concubine. He invaded Armenia and placed first his nephew Axidares and then his brother Parthamasiris on the Armenian throne. This encroachment on the traditional sphere of influence of the Roman Empire – the two great empires had shared hegemony over Armenia since the time of Nero some 50 years earlier – led to a war with the Roman emperor Trajan.

In 113 Trajan invaded Parthia, marching first on Armenia. In 114 Parthamasiris surrendered and was killed. Trajan annexed Armenia to the Roman Empire. Then he turned south into Parthia itself, taking the cities of Babylon, Seleucia and finally the capital of Ctesiphon in 116. He deposed Osroes I and put his own puppet ruler, the son of Osroes I, Parthamaspates on the throne. In Mesopotamia Osroes I’s brother Mithridates IV and his son Sanatruces II took the diadem and fought against the Romans, but Trajan marched southward to the Persian Gulf, defeated them, and declared Mesopotamia a new province of the empire. Later in 116, he crossed the Khuzestan Mountains into Persia and captured the great city of Susa.

Following the death of Trajan and Roman withdrawal from the area, Osroes I easily defeated Parthamaspates and reclaimed the Persian throne. Hadrian acknowledged this fait accompli, recognized Osroes I, Parthamaspates King of Osroene, and returned Osroes I’s daughter who had been taken prisoner by Trajan.

#

It is not mere coincidence that the Jewish uprisings occurred during Trajan’s Parthian expedition. The timing was certainly influenced by the fact that military forces had to be stripped from North Africa and Cyprus to flesh out the operations to the east of Judaea.

Trajan spent his first two years after being elevated to the purple settling affairs on the German frontier, delaying his first arrival in Rome after his appointment. Next, from 101 to 106, he fought his first campaign against Dacia (Romania) and returned victorious. Then Trajan conquered the Nabataean sandstone capital of Petra (in South Jordan) and made Nabataea a part of the new Roman province of Arabia; the Nabataean kingdom, for all intents and purposes, ceased to exist, although Petra still remained an important trading center, and the Aramaic-speaking Nabataeans later developed the Arabic script. In fact, the Nabataeans did not meekly submit to Roman rule but remained stiff-necked and potentially dangerous. It is conceivable that they allied themselves with the Jewish rebels while Trajan was distracted in the east.

Dating from the eastern conquests of Licinius Lucullus and Pompey Magnus in the 60s B. C. and into the imperial period, Roman expansion made recurrent conflict with Parthia inescapable. Previously, we pointed out that during the reign of Nero (A. D. 50s-60s) a major campaign to ensure Roman hegemony over Armenia was conducted under Cnaeus Domitius Corbulo.

Though the Neronian war between Rome and Parthia largely resulted in a stalemate, the matter was ostensibly settled by allowing Rome the final authority in naming the Armenian King. Despite the arrangement the situation remained problematic for the better part of the next half century, and during Trajan’s reign matters of the Armenian succession flared into war again.

Typically, the succession struggle within Parthia and Armenia was very complicated; boiled down to its essence, in A. D. 113 the Parthian King Osroes I was in the midst of an internal battle with a rival, Vologases III, for the kingship. In order to strengthen his position within the borders of Parthia proper, Osroes deposed the Armenian king and replaced him with his nephew. This usurpation of Rome’s previously won power to name the Armenian ruler apparently crossed a red line and provoked Trajan to move east from Rome and amass an invasion force. Some authorities find that this incident was merely a pretext for Trajan to embark on an Alexander the Great style eastern campaign of conquest that had already been decided upon.

PARTHIAN CAMPAIGN OPERATIONS

Failed attempts to broker a peace by the Parthians before any impending Roman invasion led to reasonable contemporaneous assumption that Trajan’s true motive was an Alexandrian-style campaign of conquest, and the political events simply offered a convenient excuse. Regardless of Trajan’s personal motivation for going to war he marched into Armenia in A. D. 114. Initial resistance was weak and ineffective (perhaps an indication of the debilitating internal struggle in Parthia); Armenia’s royalty was deposed and its independence stripped with its annexation as a Roman province.

Over the following two years, Trajan moved south from Armenia directly into Parthian territory. Militarily, his campaign was met with great success and resistance in the field was ineffective. With the capture of such cities and Babylon and the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon on the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, Mesopotamia and Assyria (essentially comprising modern Iraq) were annexed as Roman provinces, and the emperor received the title Parthicus. Trajan continued his march to the southeast, eventually reaching the Persian Gulf in A. D. 116. Though Dio Cassius states that Trajan would have preferred to march in the footsteps of Alexander, his advanced age (approximately 63 years) and slowly failing health forced him to abandon any such thoughts.

Despite the swiftness of the initial victories, the long-term prospects for Roman control were completely in doubt. Returning to the west and crossing the Tigris, Trajan stopped to lay siege to the desert town of Hatra. In A. D. 117, with poor supply and unable to breach the walls, the Romans suffered their first defeat of the campaign with Trajan narrowly avoiding personal injury. To add insult to the defeat, the recently “conquered” population of Jewish inhabitants began to revolt against newly installed Roman rule. For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, though religion certainly played a major part, the revolt spread to Jews living in Egypt, Cyrene and Cyprus.

Here is an rough calculation of the five legions that participated in the military operations in Parthia: Legio I Adiutrix (“helper,” later Pia Fidelis “loyal and faithful”); Legio VI Ferrata (Iron); Legio X Fretensis (re-deployed from Jerusalem); Legio III Cyrenaica (borrowed from its Cyrene/Egyptian posting); Legio XV Apollinaris (veteran of combat during the First Jewish Revolt, likely stripped from occupation duties in Syria); and Legio XVI Flavia Firma.

The Parthian operation denuded provinces to the west of any but a token occupation force, since, besides the two legions redeployed from the sectors directly involved in the rebellions, several alae (sub-units) were scrounged up from those left to guard the Jewish populations in order to augment the legions. Thus, the harassed and enraged Jewish communities in North Africa, Egypt and Cyprus saw that they had a relatively free hand to strike a decisive blow against the pagan bullies in their vicinity, particularly as messianic leaders arose to assure them that the fateful hour was nigh.

In actuality, Trajan’s “lightning triumph” was a chimera. The Parthian king Osroes remained undefeated and had escaped to the east before the advancing Romans. Now, everywhere along a front of 600 miles, the Parthians were able to harass the invader from foothills east of the Tigris. Roman supply lines were dangerously exposed, and the fortress of Hatra, bypassed by the legions, became a focus of resistance.

At this troubled moment, news reached Trajan that in regions as far afield as Cyprus, Egypt and Cyrenaica (Libya) the Jews were in revolt, ostensibly encouraged both by Jewish agents sent from Parthia and the reduction of local military strength in order to augment the legions allocated to the eastern operations. In Cyprus, where Herod the Great had owned copper mines, Jewish rebels were agitated by a local messianic pretender “Artemion” and had forced Greek and Roman citizens to fight each other in gladiatorial combat. Cyrenaica was even more badly hit, and the slaughter of Greek settlers had been horrendous. A Jewish messiah, “King Loukuas” had been proclaimed, pagan sanctuaries and the Caesareum had been attacked and Cyrene itself almost destroyed. Fourth century Christian historian Paulus Orosius records that the violence so depopulated the province of Cyrenaica that new colonies had to be established by Hadrian.

“The Jews … waged war on the inhabitants throughout Libya in the most savage fashion, and to such an extent was the country wasted that its cultivators having been slain, its land would have remained utterly depopulated, had not the Emperor Hadrian gathered settlers from other places and sent them thither, for the inhabitants had been wiped out.”-Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, 7.12.6.