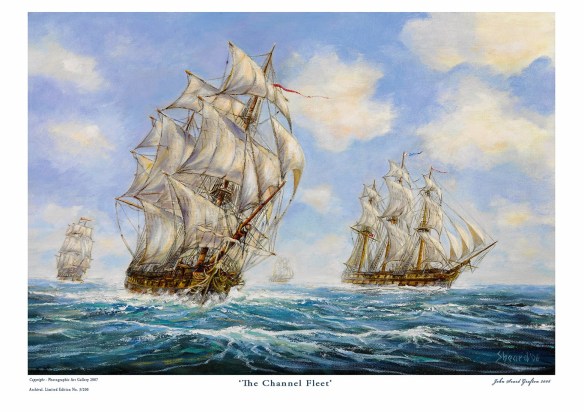

The Channel Fleet for example was dispersed by a strong gale on 3 January 1804 and the blockade of Le Havre lifted, although that of Brest was swiftly resumed. The weather claimed and damaged more ships than the French: out of the 317 naval ships lost in 1803-15, 223 were wrecked or foundered.

After Trafalgar, the British enjoyed a clear superiority in ships of the line. Napoleon subsequently sought, with some success, to rebuild his fleet. By 1809 the Toulon fleet was nearly as large as the British blockaders. However, his naval strength had been badly battered by losses of sailors in successive defeats, while his attempt to translate his far-flung territorial control into naval strength was unsuccessful. Due to the Peninsular War, Napoleon lost the Spanish navy, and the six French ships of the line sheltering in Cadiz and Vigo surrendered to the Spaniards in 1808. The Portuguese and Danish fleets were kept out of French hands, the former by persuasion, the latter by force, while Russia’s Black Sea fleet, then in the Tagus, was blockaded until the British were able to seize it. By 1810 Britain had 50 per cent of the ships of the line in the world; up from 29 per cent in 1790. Britain’s proportion of world mercantile shipping also increased: effective convoying ensured that ships could be constructed with reference to the goods to be carried, rather than their military effectiveness. Reestablished in 1793, convoys were made compulsory in 1798. The profits from trade enabled Britain to make loans and grants to European allies.

The navy had numerous tasks in European waters after Trafalgar. Some were defensive. Aside from convoying trade and offering protection against French privateers, it was necessary to retain control of home waters. This also entailed covering attacks on the Continent, especially the Walcheren expedition of 1809, which was intended to lead to the fall of the French naval base of Antwerp. Enemy trade was attacked wherever it could be found.

In the Mediterranean, the British sought to blockade Toulon as the first line of defence for British and allied interests, such as the protection of Sicily. The blockade was also intended to complement more offensive steps, including intervention in Iberia and moves to limit French influence in the eastern Mediterranean. These moves included Vice-Admiral Sir John Duckworth’s attempt to obtain the surrender of the Turkish fleet in 1807. This was unsuccessful. Duckworth sailed through the Dardanelles on 19 February 1807, destroying a squadron of Turkish frigates, but the Turks refused to yield to his intimidation and when, on 3 March, Duckworth returned through the straits he ran the gauntlet of Turkish cannon, firing stone shots of up to 800 pounds: one took away the wheel of the Canopus. Turkish resistance had been stiffened with French assistance and the British operation suffered from unfavourable winds and Duckworth’s indecision. Captain John Spanger was more successful against the French in the Ionian Islands in 1809.

The British also had defensive and offensive objectives in the Baltic. Concern about the Danish fleet led to a successful joint attack on Copenhagen in 1807: the British fleet under Admiral James Gambier helped bombard Copenhagen on 2-5 September and the city and the Danish fleet surrendered on 7 September. A vivid account by a young observer was provided by John Oldershaw Hewes (1789-1811), whose ship anchored in the Sound on 16 August:

on the 17th. Saw the Danes burn one of our merchantmen and carry one into Copenhagen. Our boats returned with two Danish vessels. Saw our bombs, brigs and frigates engaging the enemys mortar boats on the 18th. The enemys mortar boats commenced a heavy firing. The Comus frigate took the Danish frigate Fredrickswern 23rd. Sent our boats to tow our small shipping into action. At 12 o’clock one of our boats returned with three men wounded in it. One of the men had all the thick part of his thigh shot off but is now well. On the 24th at 6 o’clock at night saw the red hot shot and shells flying which looked beautiful flying in the air. At 30 minutes past 6 saw a fire break out in Copenhagen. At 8 o’clock it thundered and lightn’d most tremendous. 25th our troops on shore and the enemys forts were firing away one at another also on the 26th 27th and 28th. On the 31st the enemy hove a shell in the Charles tender and she blew up and wounded nineteen men belonging to us besides took of one of our Lieutenant’s legs broke his collar bone, cut him very bad on the head and almost knocked one of his eyes out, but he is now quite well and at Portsmouth. It killed a young man about my own age, my most particular acquaintance a masters mate, and killed two sailors besides what belonged to the vessel. On the 1st of September I went on shore with 15 sailors to make a battery close under the enemys walls. We were obliged to go when it was dark as they should not see us or else they would have certainly have shot us. We could hear them talking and playing a fiddle. It rained excessively all night and I was almost perished with wet and cold. We left it as soon as it began to get light in the morning. On the 2nd our batteries began bombarding the town. Saw the town on fire in two places…was on fire from the 2nd to the 7th on which day it surrendered…the greatest part is burnt down.

Hewes went on to serve as a clerk in the Valiant and purser of the sloop Thais, and drowned off Cape Castle, West Africa in 1811.

In 1808, the British sent warships into the Baltic in order to assist Sweden against attack by Denmark and Russia. On 25 August two British ships of the line helped 11 Swedish counterparts defeat nine Russian ships of the line off south-west Finland. The following year Vice-Admiral Sir James Saumerez led a powerful fleet to the Gulf of Finland, thus preventing the Russians from taking naval action against Sweden. However, the Russians had already conquered Finland, and were able to force the Swedes to accept a dictated peace. Thereafter, as Sweden was forced into the French camp, Saumarez took steps to protect British trade and, crucially, naval stores: much of the timber, tallow, pitch, tar, iron and hemp required for the navy came from the Baltic.

The general situation was more favourable than in 1795-1805, particularly after the Spanish navy and naval bases were denied France in 1808, although there were fewer opportunities than earlier to increase the size of the navy by adding French prizes. The blockaded French navy was no longer a force that was combat-ready. The longer it remained in harbour the more its efficiency declined: officers and crews had less operational experience. It remained difficult to predict French moves when at sea, but the French were less able to gain the initiative than hitherto. The French and allied squadrons that did sail out were generally defeated. These frequently overlooked engagements were important because a run of French success would have challenged British naval control.

On 25 September 1805 Samuel Hood and the blockading squadron off Rochefort attacked a French frigate squadron bound for the West Indies with reinforcements: four of the five frigates were captured, although Hood had to have his arm amputated after his elbow was smashed by a musket shot. On 6 February 1806 Duckworth and seven of the line engaged a French squadron of five of the line that had escaped from Rochefort off Saint Domingue in the West Indies. The superior British gunnery brought Duckworth a complete victory: three of the French ships were captured and two driven ashore and burnt. During the battle a portrait of Nelson was displayed abroad the Superb. On 13 March 1806 Warren captured two warships sailing back from the East Indies as they neared France. Further afield, the Dutch squadron in the Indian Ocean was destroyed at Gressie on 11 December 1807. On 4 April 1808 an escorted Spanish convoy was intercepted off Rota near Cadiz, the escorts dispersed and much of the convoy seized. On the night of 11-12 April 1809 a French squadron in Basque Roads was attacked by fireships. Although they did no damage to the French warships, many ran aground in escaping the threat. They were attacked by British warships on 12 April and four were destroyed. However, a failure to press home the attack led to recriminations between the admirals and a court martial. Two years later, on 13 March 1811, a squadron of four frigates under Captain William Hoste, one of Nelson’s protégés, engaged a French squadron of six frigates under Dubourdieu off Lissa in the Adriatic: Lissa was a British base that the French were trying to seize. As the French approached, Hoste hoisted the signal “remember Nelson” to the cheers of his crew. Thanks to superior British seamanship and gunnery, the French were defeated with the loss of three frigates. Hoste kept the Adriatic in awe. Frequently, foreign warships had to be attacked while inshore or protected by coastal positions, a situation that enhanced the value of Britain’s clear superiority in vessels other than ships of the line. In August 1806 the Spanish frigate Pomona anchored off Havana close to a shore battery was captured by two British frigates.

These engagements were the highpoints of a prolonged and often arduous process of blockade in which British squadrons policed the seas of Europe and, to a far lesser extent, the rest of the world. The history of these squadrons was often that of storms and of disappointed hopes of engaging the French. Blockade was not easy. This was especially true off Toulon due to the prevailing winds. The exposure of warships to the constant battering of wind and wave placed a major strain on an increasingly ageing fleet. The Channel Fleet for example was dispersed by a strong gale on 3 January 1804 and the blockade of Le Havre lifted, although that of Brest was swiftly resumed. The weather claimed and damaged more ships than the French: out of the 317 naval ships lost in 1803-15, 223 were wrecked or foundered. Tropical stations could be particularly dangerous. In 1807 Troubridge and the Blenheim disappeared in a storm off Madagascar. Blockading squadrons could be driven off station by wind and weather: this was the case with the small watching squadron off Toulon when the French sailed in May 1798.