A page from the Codex Mendoza depicting an Aztec warrior priest and Aztec priest rising through the ranks of their orders.

Tenochtitlan was divided into four quarters or campans. Following its conquest by Tenochtitlan in 1473 the neighbouring Aztec city of Tlatilolco became a fifth `quarter’. Each quarter comprised several calpulli – wards or kin-groups (of which there appear to have been 20 in all by 1519) – divided in turn into smaller family groupings called tlaxilacalli, of which there were probably two or three per calpulli. This same organisation was transferred to the army when it was mustered, with calpulli units – each serving under its own elected clan war-chief, a tiachcauh – combined into four (later five) larger divisions under the campan chieftains. Sometimes, when very numerous, a campan’s warriors were subdivided into smaller units, each comprising at most two or three calpulli. Each calpulli had its own standard and went into battle shouting the name of its ward.

Unit organisation throughout Mesoamerica was based on the vigesimal system, the smallest unit being the pantli, or `banner’, of 20 men. Technically the next unit should have been the company of 400 men (tzontli, or 20 3 20) and the largest was certainly the xiquipilli of 8,000 men (20 3 400), but there is sufficient evidence to indicate that units of 100 and 200 men also existed, perhaps as subdivisions of the tzontli. References even occur to bodies 800-1,000 strong, but these were probably combinations of several smaller units. Quite how these various unit sizes relate to the administrative structure of campan and calpulli outlined above is unclear. It has been suggested that each calpulli fielded 400 men and each campan 8,000. Probably Sahagun is referring to bands of 200-400 men when he describes Aztec units as comprising men of a `particular group or kindred’, which is presumably an allusion to either a tlaxilacalli or a calpulli.

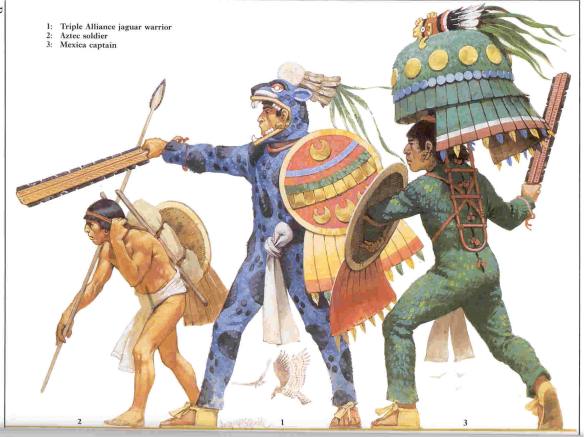

Units as small as 200 men, and probably those of 100, each had their own standard (probably that of the unit’s commander), which was placed in the centre of the unit in battle. There is also some evidence to suggest that individual units may have used some sort of distinguishing combination of colours for identification, presumably in the form of an item of clothing. Certainly the chronicler known as the Anonymous Conquistador, after describing Aztec war-suits, refers to how `one company will wear them in white and red, another in blue and yellow, and others in further different combinations’, and Diaz del Castillo wrote of the defenders of Tenochtitlan in 1521 that `each separate body of the Mexicans was distinguished by a particular dress and certain warlike devices’. In the 18th century Clavigero, using earlier sources, wrote that units were `distinguished by the colour of the plumage which the officers and nobles wore over their armour’. How this worked in conjunction with the complicated Aztec strictures regarding the wearing of different colours and costumes, alluded to in the figure captions below, remains unclear.

The size of an Aztec army depended on the task in hand. It could involve no more than the noble elements of the Triple Alliance itself, including the Eagle and Jaguar Warriors; or a full muster of the warrior-class, i. e. all of those who had opted for a `full-time’ military career as opposed to the common militiamen (the yaoquizqueh); a general call-to-arms of a greater or smaller part of the entire population; a universal muster of the Triple Alliance and some or many of its tributary towns; or a combination of any of these – for instance, an army might comprise just the warrior-classes of the Triple Alliance and several tributaries. The majority of field-armies appear to have been in the region of 20- 50,000 strong, but for the campaign against Coixtlahuaca in 1506-7 reputedly 25 xiquipilli, or 200,000 men, were raised – not an entirely impossible figure if the highest of the various estimates of Mexico’s population c. 1500 (between five and 25 million) are at all accurate, but certainly highly improbable, for logistical reasons if no other. Troops of tributary towns were technically obliged to serve once a year, the normal practice being for them to be mustered by the town’s own tlatoani and then (in the words of a Relacion Geografica) `handed over to the Mexican captain sent by Moctezuma’s government, and this man they acknowledged as captain and obeyed’.

A general call-up was announced in Tenochtitlan by a priest dressed as the war-god Painal (`Swift Runner’), who, wearing a black mask edged with white dots and with his body painted blue and yellow, ran through the streets with a rattle and a shield while the town’s wardrum was beaten. The people then assembled at the main temple of each quarter, where arms were issued from those stored in an arsenal (the tlacochcalco or `house of darts’) situated in the temple entrance. Gomara records that these held bows, arrows, slings, `pikes’, darts, clubs, macanas, and shields, and a smaller number of helmets, greaves, and vambraces. Diaz del Castillo notes what must have been additional arsenals in the palace itself, where Moctezuma II `had two buildings filled with every kind of arms, richly ornamented with gold and jewels’, including all of the arms listed by Gomara plus `much defensive armour of quilted cotton ornamented with feathers in different devices’. The richer quality of the palace arsenals indicates that the warrior-class must have been supplied from these, both in war and in the Ochpaniztli ceremony. Stock-levels in these arsenals were maintained by means of the tribute payments exacted from the Alliance’s subject provinces, which by the Conquest period seem to have been required to supply over 600 war-suits, armours, and shields at the end of every 260 days, as well as considerable quantities of slings, slingstones, bows, arrows, flint and obsidian blades, and 32,000 canes to make spears and darts. Since the Valley of Mexico was at too high an altitude to cultivate cotton the Triple Alliance was, in fact, entirely dependent on its tributaries for cotton cloth and armour.

Each unit was responsible for the transport of its own victuals, which were provided by the state. Where the campaign was local each warrior carried his own provisions on his back in a net bag, but for campaigns further afield tlamemes, or porters, were used. Sometimes these were sent ahead to leave supply caches along the army’s line of march for as long as they were in Triple Alliance territory. Towns en route were expected to provide additional supplies and equipment; where they failed to do so provisions were sometimes taken by force, but any form of unauthorised looting, in either friendly or even enemy territory, was otherwise a capital offence, be it so much as an ear of corn plucked from the roadside. Women generally accompanied the army to cook and to carry additional household equipment that might be needed. Even with these relatively sophisticated logistical arrangements, however, ensuring the availability of adequate supplies in such a thinly populated land – especially once the army had entered enemy territory – was no easy task. Consequently delays, lengthy halts, and long sieges, all presented insurmountable difficulties. As a result sieges were rarely attempted, most towns being taken by frontal assault.

Sahagun records that on the march the army adhered to a strict order of precedence. Priests went first, followed by the army’s generals with the Eagles, Jaguars, and veteran warriors; next came the rest of the Triple Alliance’s own troops; then those of Tlatilolco, Acolhuacan, Tepaneca, Xilotepec and `the so-called Quaquata’ (i. e. men with slings tied round their heads, a name Sahagun elsewhere applies to the Matlatzinca); and after them the contingents of other tributary towns and provinces. Strict military discipline was enforced both on the march and in battle. When the army was in array `no-one might break ranks or crowd in among the others’, and chieftains would `then and there slay or beat whoever introduced confusion’. Those found guilty of almost any sort of battlefield misconduct were customarily stoned to death following a court-martial hearing.

A STANDING ARMY?

Modern authorities are unanimous that the Aztecs had no standing army. Nevertheless, as we have already seen, they did have men whose working lives were dedicated to military service and whose career advancement could only come through that service; who earned their keep by fighting; and who were housed and fed by the state. Certainly there is never any suggestion in a contemporary source that non-noble warriors, at least of the rank of tequihuah and up, had any other form of income or livelihood, other than receiving – like tiachcauhqueh (men who had taken three captives) – gifts from parents in payment for providing their children with a military education, and certainly in this respect they were full-time professionals. However, they remained collections of individually courageous warriors rather than properly constituted, formally administered and disciplined companies, and outside of their service either on campaign or in a civil administration capacity – even accepting that they were forever at the Speaker’s beck and call – their time appears to have been effectively their own. In addition it needs to be borne in mind that all such men were what we would today consider officers, or at least senior NCOs, so that there was no such thing as a permanent rank-and-file; military service was very much a secondary responsibility for Aztec commoners, whose principal duty was to farm the land. In this regard if no other, the Aztecs can hardly be considered to have had a standing army.

However, this conclusion calls for an explanation of the frequent Spanish references to the existence of Aztec `garrisons’ (guarniciones), since this term automatically implies a permanent military establishment. Diaz records that `the great Moctezuma kept many garrisons and companies of warriors in all the frontier provinces. There was one at Soconusco to guard the frontier of Guatemala and Chiapas, another at Coatzacualcos and another on the frontier of Michoacan, and another on the frontier of Panuco, between Tuxpan and the town which we called Almeria on the north coast.’ Relaciones Geograficas remark on the presence of other such garrisons at Oaxaca, at Calixtlahuacan in Tolucan, at Tututepec and Chilapa on the frontiers of Yopitzinco, and elsewhere, while by 1519 `a large garrison of warriors’ had reportedly been installed in Cholula. However, in 16th century Spanish the term guarnacion actually denoted not a garrison as we would understand it, but rather just a detached force or a body of soldiers, so that most of the generally vague allusions to Aztec `garrisons’ probably signified small forces present in an area on no more than a temporary basis.

The few garrisons for which a more convincing case might be made appear to have been established as colonial settlements rather than military outposts – the `garrison’ colony of Oaxaca, for instance, was, according to Diego Duran, made up of 900 married men and their families drawn from Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, Chalco, Xochimilco, Cuernavaca, and the Mazahua; while those to be settled on another occasion at Oztuma, Alahuiztla, and Teloloapan on the Tarascan frontier consisted of 2,000 men and their families, gathered from more than 40 towns. Doubtless such men as were selected would have been of military age and would be expected to provide the nucleus of any locally mustered force, but it is not suggested anywhere that such service should be provided on a full-time basis, even though those settled on the Tarascan frontier are warned to be constantly on their guard because of the enmity between the Tarascans and the Aztecs.

However, such `garrison’ colonists may have been a cut above the usual class of farmer-militiamen. From Diaz’s account it would appear that the garrison on the Huaxtec frontier, based in Xiuhcoac, was maintained by tribute and supplies exacted from the other towns and villages in the area and was active on a regular-enough basis to have inspired fear throughout the region, an unlikely occurrence if it just consisted of commoners performing their obligatory military duties. Diaz implies that Xiuhcoac could put as many as 4,000 men in the field in 1520, many of whom were doubtless locals whose tribute payments to the state took the form of military service. The `garrison’ of Calixtlahuacan in Tolucan, originating with Aztec colonists settled there in the 1470s, is recorded fielding a similarly sizeable force in 1521, when Cortés wrote that it and the local Mazahua population suffered 2,000 dead in an engagement against a combined Spanish-Otomi force.