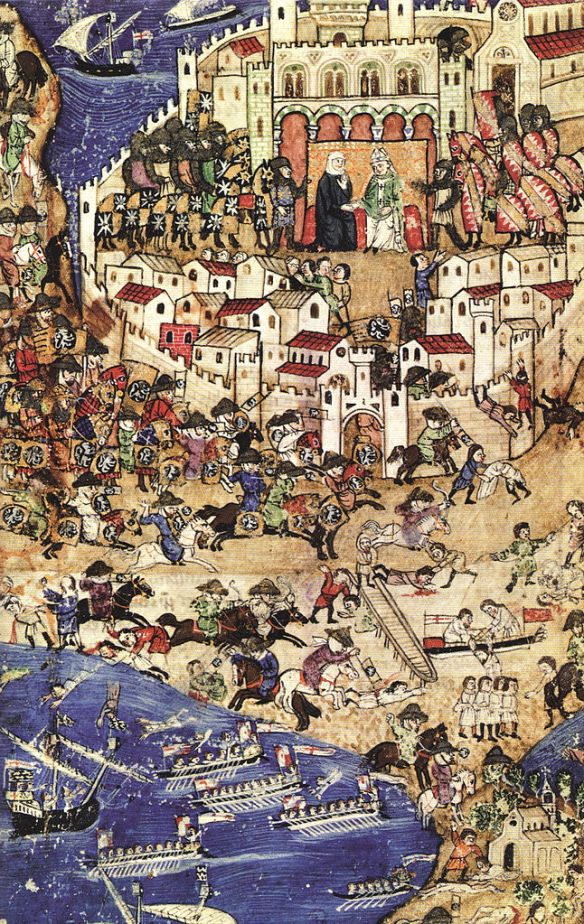

The Fall of Tripoli in 1289 triggered frantic preparations to save Acre.

Siege of Acre 1291 – Guillaume de Clermont Defending Ptolemais from the Saracen invasion. The fall of Acre signaled the end of the Jerusalem crusades. No effective crusade was raised to recapture the Holy Land afterwards, though talk of further crusades was common enough. By 1291, other ideals had captured the interest and enthusiasm of the monarchs and nobility of Europe and even strenuous papal efforts to raise expeditions to retake the Holy Land met with little response.

Long before his death, Baybars had arranged for a smooth succession. Alas, this did not guarantee an easy transition. His son and heir, Baraka, was forced by a rival mamluk faction to abdicate, and Baraka’s successor was likewise deposed, in 1279. The sons of Baybars were kept on a form of house arrest at Karak in Transjordan, though eventually they were recalled to live their final days in Cairo. A last descendant, a great-great-grandson of Baybars, died in 1488, his connection to the founding of the Mamluk regime all but forgotten. The man who supplanted the sons of Baybars as sultan was an elder statesman, an old Bahri colleague of Baybars named Qalawun (also Qalavun), who was a veteran of the campaigns in Syria and Armenia. Like his former comrade Baybars, Qalawun was a Qipchaq Turk who had been captured, enslaved, and purchased to become a member of Egypt’s mamluk corps. His nickname, “al-Alfi” or “Thousand-Coin,” alluded to the steep price he was said to have fetched. Once he was recognized as sultan, most of Qalawun’s attentions were taken up by the twin threats of rebel amirs in northern Syria and the Mongol il-khan Abaqa, who still hoped to take Syria for the Mongols. The rebels, though, were eventually placated and, with typical Mamluk efficiency, were brought as allies against the Mongols, who met Qalawun in battle near Homs-their second battle there-in October 1281 and were soundly defeated, their second defeat there. When the new ilkhan converted to Islam and sent envoys to curry favor with the sultan, his gesture of friendship was rebuffed like that of a whingeing underclassman. In Cairo the Mongol threat was beginning to lose its bite.

Qalawun also prosecuted jihad against the Franks, continuing Baybars’s plan to drive them from Syria altogether. They were, in any case, truly just clinging to the coast of Syria. Only Tripoli now remained of the original Frankish capitals, the capital of the kingdom of Jerusalem having been moved to Acre in Saladin’s day. Even at Acre the Frankish crown was in dispute, with the Lusignan Hugh III of Cyprus claiming it against the demands of the king of Sicily, Charles of Anjou. The remaining Frankish holdings at Sidon, Tyre, and Beirut were thus obliged to recognize one claimant over the other. The Frankish states had divided themselves; all Qalawun had to do was conquer them. In May 1285 al-Marqab (Margat) fell to Qalawun, who repaired it and stationed a garrison there, its Hospitaller occupants given safe passage to Tripoli. The coastal fort of Maraqiyya (Maraclea), which had so thwarted Baybars, was now easily taken thanks to a deal worked out with Bohemond VII. Following standard procedure, it was dismantled. In 1287 an earthquake badly damaged the defense of the port of Latakia, and Qalawun wasted no time in snapping it up.

It was at about this time that some Franks begged him to capture Tripoli. This perhaps requires some explanation. Tripoli’s last lord, Bohemond VII, had died in 1287; in this vacuum, power in the city was divided among the Frankish nobility, the Italian merchant communes, and the military orders, all of whom were at each other’s throats. When it seemed that a sister of the dead Bohemond would be able to take power with Genoese backing, the Venetians implored Qalawun to put a stop to it. And stop it he did. In March 1289 his army began its siege of Tripoli. It was slow going for Qalawun, as a renewed sense of urgency- not to say doom-struck the Franks remaining in Syria. The Italian communes all provided galleys, as did Frankish Cyprus. A corps of knights came from Acre.

After nearly a month of constant bombardment from Mamluk siege engines, however, Tripoli’s stout defense began to crumble. The Italians, sensing a turn in fortune, quickly took ship and fled. On April 26, 1289, the city fell in an all-out attack. It is said that every man found in the streets was killed, and everyone else was sold into captivity. Those who could fled to Cyprus. So bent on cleansing the land of Frankish pollution were Qalawun’s men that some were reported to have ridden their horses into the sea in pursuit of Franks taking refuge on a nearby island, dragging their mounts by their reins until they reached the place, where everyone in hiding was cut down. The bones of the dead lord Bohemond VII were dug up and scattered to the wind. His city, like all the others on the coast, was demolished. Some few Frankish castles in the vicinity fell soon after Tripoli, and the Italian lord of Jubayl readily handed over his town to Qalawun. By now three of the four Frankish states, Edessa, Antioch, and Tripoli, had been eradicated. Acre, itself a place-holder for what was left of the old kingdom of Jerusalem, was alone and clearly bound for destruction along with what remained of the orts and crumbs of Crusader Syria. However, Qalawun knew that any siege at Acre would be a long and bitter one, in which the Franks would pull out all the stops to retain their last serious foothold on the Levantine coast. So, to bide his time, he made a temporary truce with Acre and returned to Egypt to rest, resupply, and build up an unstoppable army.

In August 1290 Acre’s moment came. A riot in the city, in which some Franks killed a number of Muslim townsmen (possibly merchants), provided Qalawun’s pretext for claiming the Franks had broken their truce. He called for jihad against these perfidious Franks and marched at the head of his Egyptian troops, sending word for his Syrian amirs to assemble their men and siege equipment. But fate struck Qalawun before it saw to Acre; just a few miles on the road from Cairo, the aging sultan, ailing from a sickness contracted months earlier, died.

At this surprising turn of events, it might have seemed that the Franks had been blessed with another miracle. In fact the old sultan’s death provided only a brief respite. In March 1291 his son and heir, al-Ashraf Khalil, renewed his father’s campaign. Qalawun’s funeral was used as a pulpit from which to preach the jihad in Egypt; in Syria the sultan’s representative launched a carefully planned program designed to spur the populace of Syria to jihad. The preachers were so successful that volunteers were said to outnumber the regular troops, and the whole populace pitched in, despite rain and snow, to help haul the siege equipment overland to be gathered by contingents of the army. Peasants and townsmen were joined by “jurisprudents, teachers, scholars, and the pious” in their heavy lifting. Armies from Hama, Homs, Tripoli, and other fortresses arrived to rendezvous with the Egyptian and Palestinian troops. Few could doubt that the new sultan had managed to mobilize most of his domains for this one, final siege.

Once arrived at Acre on April 6, al-Ashraf’s army found a large, well-fortified city, its garrison supplemented by contingents from the Hospitallers and Templars. Frankish ships carrying mangonels fired down upon those Muslim divisions encamped closest to the sea, and Frankish knights rode out daily to harass and provoke the soldiers engaged in the siege. At one point the Templars and Hospitallers led a dangerous sortie that was thwarted only by a last-minute warning to the sultan. Eventually a contingent from Cyprus led by King Hugh himself arrived, though Hugh did not linger. The Mamluks never paused in their bombardment and sapping operations. Finally, their persistence paid off: a tower collapsed, and the army now got clear of the outer walls and confronted the city’s inner defenses, where some of the most bitter fighting with the military orders took place. In mid- May a group of Acre’s notables emerged to negotiate a truce but were rejected. Al-Ashraf instead offered the Franks safe conduct provided they abandon the city. The deal never got very far, for at this point someone fired a mangonel from the city and the sultan was nearly killed. Negotiations were canceled, and the bombardment began afresh.

At dawn on May 18 al-Ashraf ordered the drums-all three hundred of them-to signal what would be the Mamluk’s final offensive. As the doom of Acre was drummed into the morning light, arrow fire denuded the walls of their defenders. Despite intense fighting from the Templars and Hospitallers, the Mamluk troops were finally able to force their way into the city. Al-Ashraf’s banners were flying on Acre’s walls by midday. The Franks fled to the port to escape or else holed up in the remaining towers and defenses. While al-Ashraf’s regular troops were occupied with these remaining defenders, the volunteers who accompanied the army broke ranks and began pillaging the city at will. One man was said to have needed three rows of porters to carry all his plunder back to Cairo. Virtually all the remaining Frankish defenders had surrendered, save in one tower, where a contingent of Templars, Hospitallers, and other knights were cornered with some civilians. They had arranged to surrender too, but some of the Mamluk troops, perhaps worried that the jihad volunteers were taking the best of the plunder, rushed in before the tower could be evacuated and began seizing the women and children as captives. At this the Templars preferred to stand and fight and, closing the gates, killed whatever Muslims they had managed to trap inside their tower. Three days later, however, they agreed to surrender. Again some undisciplined Mamluk troops broke the terms of their agreement, slaughtering the knights that emerged and seizing the civilians for captivity. The surrender turned into the bloodiest fighting of Acre’s last hours. In retaliation the Templars took Muslim prisoners and began killing them and attacking any troops that approached the tower. One of the Muslims trapped in the tower lived to tell the tale, perhaps the last Muslim eyewitness voice from Outremer: “I . . . was among the group who went to the tower and when the gates were closed we stayed there with many others. The Franks killed many people and then came to the place where a small number, including my companion and me, had taken refuge. We fought them for an hour, and most of our number, including my comrade, were killed, but I escaped in a band of ten persons who fled in their path. Being outnumbered, we hurled ourselves toward the sea. Some died, some were crippled, and some were spared for a time.”

Al-Ashraf, however, was not about to let these Templar holdouts ruin his victory. He ordered the tower sapped, and the defenders inside quickly evacuated the premises. The dismantling of Acre’s other defenses began immediately. Carrier pigeons brought the news of the fall of Acre to Damascus on the same day, and the city broke out in public rejoicing. Saved from the rubble was the Gothic façade of one of Acre’s churches. Its handsomely crafted entryway, with its slender columns and triple-lobed recess, was carried off to Cairo, where it serves as an entrance to the madrasa and tomb complex of al-Ashraf’s half-brother, the sultan al-Nasir Muhammad.

At the time, no one seems to have questioned all the slaughter at Acre, estimated in the tens of thousands. Both sides knew what Acre meant and that this was Outremer’s last stand. Only one historian, al- Yunini (d. 1326), was able to look back a generation later and put the violence in context: “In my view this was [the Franks’] reward for what they did when they conquered Acre from the martyred sultan Saladin. Although they had granted amnesty to the Muslim inhabitants, they betrayed them after the victory, killing all except a few high-ranking amirs. . . . Thus God requited the unbelievers for what they did to the Muslims.” In the wake of al-Ashraf’s reconquest of Acre, the Franks remaining in Sidon, Beirut, Tyre, and Haifa soon surrendered their cities, providing the sultan little or no resistance when his men took them. At Tyre, for example, the Muslim commander claimed to have found only a few dozen old men and women. The last Templar forts at Antartus (Tortosa) and .Atlith were easily taken too. With the goal of nearly every Muslim ruler in the Near East since the coming of the Franks finally realized, al-Ashraf visited Damascus, covered in glory. The city was decorated and illuminated, and the sultan trod upon runners of satin that indicated his path from the city gate to the palace. Before him the sultan paraded 280 Frankish prisoners in chains; one carried an inverted Frankish banner, the other a banner festooned with the hair of some of his slain comrades. People from the city and from miles around lined the streets to view the spectacle: scholars, mystics, peasants, merchants, Christians, and Jews. The satin was rolled out again for al-Ashraf when he finally returned to Cairo in triumph, piously ending his march at the tomb of Qalawun, a gesture of humility meant to suggest that his deed was merely that of finishing a job started