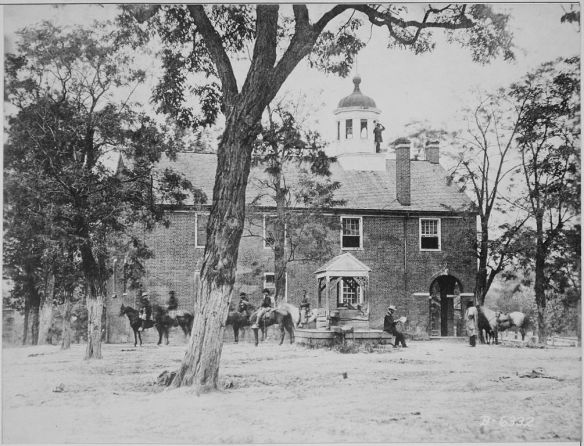

Fairfax Court House, Virginia by Matthew Brady

John Singleton Mosby (December 6, 1833 – May 30, 1916), nicknamed the “Gray Ghost”, was a Confederate Army cavalry battalion commander in the American Civil War. His command, the 43rd Battalion, 1st Virginia Cavalry, known as Mosby’s Rangers or Mosby’s Raiders, was a partisan ranger unit noted for its lightning quick raids and its ability to elude Union Army pursuers and disappear, blending in with local farmers and townsmen. The area of northern central Virginia in which Mosby operated with impunity was known during the war and ever since as Mosby’s Confederacy. After the war, Mosby worked as an attorney and supported his former enemy’s commander, President Ulysses S. Grant, serving as the U. S. consul to Hong Kong and in the U. S. Department of Justice.

Captain John S. Mosby, a former cavalry scout who had been given permission in January to recruit a body of partisans for operations in the Loudoun Valley, part of a region to be known in time as “Mosby’s Confederacy,” so successful were he and his Rangers in bedeviling and defeating the bluecoats sent there to capture or destroy him. Twenty-eight years old and weighing barely 125 pounds, the slim, gray-eyed Virginian first attracted wide attention by his capture, at Fairfax on a night in early March, of Brigadier General E. H. Stoughton, a Vermont-born West Pointer, together with two other officers, 30 men, and 58 horses. Mosby, who at present had fewer men than that in his whole command, entered the general’s headquarters, stole upstairs in the darkness, and found the general himself asleep in bed. Turning down the covers, he lifted the tail of the sleeper’s nightshirt and gave him a spank on the behind.

“General,” he said, “did you ever hear of Mosby?”

“Yes,” Stoughton replied, flustered and half awake; “have you caught him?”

“He has caught you,” Mosby said, by way of self-introduction, and got his captive up and dressed and took him back through the lines, along with virtually all of his headquarters guard, for delivery to Fitzhugh Lee the following morning at Culpeper.

In January 1863, Stuart, with Lee’s concurrence, authorized Mosby to form and take command of the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry. This was later expanded into Mosby’s Command, a regimental-sized unit of partisan rangers operating in Northern Virginia. The 43rd Battalion operated officially as a unit of the Army of Northern Virginia, subject to the commands of Lee and Stuart, but its men (1,900 of whom served from January 1863 through April 1865) lived outside of the norms of regular army cavalrymen. The Confederate government certified special rules to govern the conduct of partisan rangers. These included sharing in the disposition of spoils of war. They had no camp duties and lived scattered among the civilian population. Mosby required proof from any volunteer that he had not deserted from the regular service, and only about 10% of his men had served previously in the Confederate Army.

Having previously been promoted to captain, on March 15, 1863, and major, on March 26, 1863, in the Provisional Army of the Confederate States, Mosby was soon promoted to lieutenant colonel on January 21, 1864, and to colonel, December 7, 1864.

Mosby is famous for carrying out a daring raid far inside Union lines at the Fairfax County courthouse in March 1863, where his men captured three Union officers, including Brig. Gen. Edwin H. Stoughton.

Mosby endured his first serious wound of the war on August 24, 1863, during a battle near Annandale, Virginia, when a bullet hit him through his thigh and side. He retired from the field with his troops and returned to action a month later.

Mosby endured a second serious wound on September 14, 1864, while taunting a Union regiment by riding back and forth in front of it. A Federal bullet shattered the handle of his revolver before entering his groin. Barely staying on his horse to make his escape, he resorted to crutches during a quick recovery and returned to command three weeks later.

Mosby’s successful disruption of supply lines, attrition of Union couriers, and disappearance in the disguise of civilians caused Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to tell Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan:

The families of most of Moseby’s men are know[n] and can be collected. I think they should be taken and kept at Fort McHenry or some secure place as hostages for good conduct of Mosby and his men. When any of them are caught with nothing to designate what they are hang them without trial.

On September 22, 1864, Union forces executed six of Mosby’s men who had been captured out of uniform in Front Royal, Virginia; a seventh (captured, according to Mosby’s subsequent letter to Sheridan, “by a Colonel Powell on a plundering expedition into Rappahannock”) was reported by Mosby to have suffered a similar fate. William Thomas Overby was one of the men selected for execution on the hill in Front Royal. His captors offered to spare him if he would reveal Mosby’s location, but he refused. According to reports at the time, his last words were, “My last moments are sweetened by the reflection that for every man you murder this day Mosby will take a tenfold vengeance.” After the executions a Union soldier pinned a piece of paper to one of the bodies that read: “This shall be the fate of all Mosby’s men.”

After informing General Robert E. Lee and Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon of his intention to respond in kind, Mosby ordered seven Union prisoners, chosen by lot, to be executed in retaliation on November 6, 1864, at Rectortown, Virginia. Although seven men were duly chosen in the original “death lottery,” in the end just three men were actually executed. One numbered lot fell to a drummer boy who was excused because of his age, and Mosby’s men held a second drawing for a man to take his place. Then, on the way to the place of execution a prisoner recognized Masonic regalia on the uniform of Confederate Captain Montjoy, a recently inducted Freemason then returning from a raid. The condemned captive gave him a secret Masonic distress signal. Captain Montjoy substituted one of his own prisoners for his fellow Mason (though one source speaks of two Masons being substituted). Mosby upbraided Montjoy, stating that his command was “not a Masonic lodge”. The soldiers charged with carrying out the executions of the revised group of seven successfully hanged three men. They shot two more in the head and left them for dead (remarkably, both survived). The other two condemned men managed to escape separately.

On November 11, 1864, Mosby wrote to Philip Sheridan, the commander of Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley, requesting that both sides resume treating prisoners with humanity. He pointed out that he and his men had captured and returned far more of Sheridan’s men than they had lost. The Union side complied. With both camps treating prisoners as “prisoners of war” for the duration, there were no more executions.

On November 18, 1864, Mosby’s command defeated Blazer’s Scouts at the Battle of Kabletown.

Mosby had his closest brush with death on December 21, 1864, near Rector’s Crossroads in Virginia. Apparently having dinner with a family in a Southern home, Mosby was fired on through a window, and the ball entered his abdomen two inches below the navel. He managed to stagger into the bedroom and hide his coat, which had his only insignia of rank. The commander of the Union detachment, Maj. Douglas Frazar of the 13th New York Cavalry, entered the house and-not knowing Mosby’s identity-inspected the wound and pronounced it mortal. Although left for dead, Mosby recovered and returned to the war effort once again two months later.

Several weeks after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender, Mosby simply disbanded his rangers on April 21, 1865, in Salem, Virginia, as he refused to surrender formally. Many of his men obtained official parole documents from the Federals and returned to their homes, but Mosby himself traveled southward with a small party of officers to join up with General Joseph E. Johnston’s army in North Carolina. Before he reached his fellow Confederates, he read in a newspaper of Johnston’s surrender. Some of his colleagues proposed that they return to Richmond and capture the Union officers who were occupying the White House of the Confederacy, but Mosby rejected the plan, telling them, “Too late! It would be murder and highway robbery now. We are soldiers, not highwaymen.”

Mosby was a wanted man, with a $5000 bounty on his head issued by Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock. He eluded capture in the area of Lynchburg, Virginia, until the end of June, when Ulysses S. Grant intervened directly in the case and paroled him.