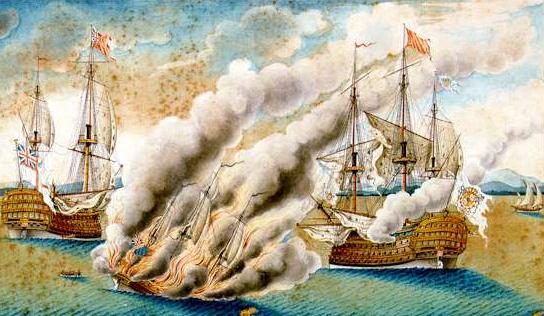

The Franco-Spanish fleet commanded by Don Juan José Navarro drove off the British fleet under Thomas Mathews near Toulon in 1744. The British fire-ship Anne Galley blows up after being hit by a broadside from the 64-gun Spanish warship Hércules.

The continued existence of the French fleet had considerable, potentially crucial, strategic consequences at the time of the ’45. This existence reflected the British failure to defeat the French in 1744. Then opportunities had presented themselves both in the Channel and in the Mediterranean. The Brest fleet under de Roquefeuil had moved down the Channel to cover a projected invasion of England, but the British attempt to defeat the French fleet had been wrecked by a storm that hit both fleets, and also sank many of the invasion transports in the Channel ports. In the Mediterranean, the battle of Toulon (11 February) had been indecisive, leading to political controversy within Britain, although it was not easy to decide how best to engage a Franco-Spanish fleet when Britain was not at war with France. The British pressed the Spaniards hard, while the French exchanged fire at a range from which they could not inflict much damage. The British rear under Vice-Admiral Richard Lestock did not engage due to Lestock’s determination to keep the line. Lestock and the British commander, Admiral Thomas Mathews, had had disagreements and he was wilfully unhelpful, but Mathews had given contradictory instructions. The net effect was that the British squandered their numerical advantage. The French were able to come to the assistance of the Spaniards, the British withdrew, and when on 12 February they returned to pursue the Bourbon fleet, the latter was able to retire with the loss of only one already badly damaged ship, the Spanish Poder: the damage it suffered was a testimony to the impact of British broadsides. Mathews was cashiered, and the battle discredited the 80-gun ships of the fleet: lacking the firepower of 90 and 100-gun three-deckers, they appeared undergunned for their limited seaworthiness. Nevertheless, the Franco-Spanish fleet in the Mediterranean did not subsequently mount a comparable challenge.

In 1745 the continued existence of a powerful French navy increased the danger of a French landing on the south coast, an event which was in fact erroneously reported. The government ordered the navy to prevent French moves in the Channel, Vice-Admiral William Martin being instructed in July, when information was received that the French had decided to invade, to prevent any ships from leaving Brest. Newcastle wrote in October 1745, “Admiral Martin is cruising off the Lizard with a very considerable squadron. Admiral Vernon continues in the Downs; and we have a great number of small ships in different parts of the Channel”.

Cumberland’s pursuit of Bonnie Prince Charlie was to be constrained by the fear of an invasion of the south coast. In December 1745, Newcastle wrote to him:

His Majesty having received an account from Admiral Vernon, that a considerable number of vessels, besides small boats, are assembled at Dunkirk, and that there is the greatest reason to believe that an attempt will be immediately made to land a body of troops from hence on some part of the southern or eastern coast. your Royal Highness should immediately return to London, with the rest of the cavalry and foot, that are now with you.

The order was to be countermanded, but it reflected the impact of French naval power on British military planning. Nevertheless, the British were able to take for granted the use of the sea to move troops across the North Sea and up the east coast, thus avoiding many of the problems posed by an invasion when most of the army was abroad, and also enabling British forces to operate or maintain a presence in two spheres at once. British naval power also blocked French invasion schemes.

No crisis comparable to the ’45 was ever again to occur. During subsequent French invasion attempts in 1759, 1779 and 1805 there was no indigenous pro-French activity and, therefore, the strategic situation was different. In December 1770, when war with the Bourbons (France and Spain) over the Falkland Islands appeared imminent, there was opposition in the Council to the idea of sending a fleet to Gibraltar and Jamaica, because it was feared that it might leave the British “coasts exposed to be insulted”, not because of the prospect of any co-operation with domestic rebellion. In 1745-6 the British army was torn between two competing demands: the Jacobite army and the prospect of a French invasion. By making the latter more or less likely, the balance of naval power affected operations against the Jacobites who were the more immediate military threat. In contrast, during subsequent invasion years, it was possible to match British army and naval strength and deployments to a common threat.