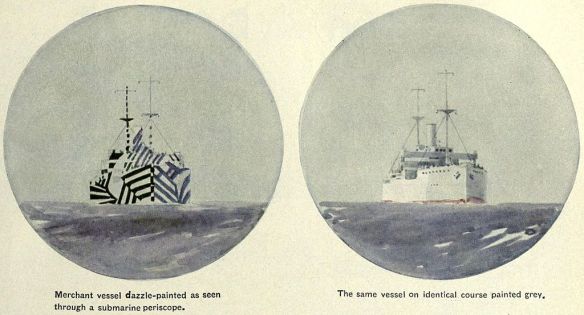

Claimed effectiveness: Artist’s conception of a U-boat commander’s periscope view of a merchant ship in dazzle camouflage (left) and the same ship uncamouflaged (right), Encyclopædia Britannica, 1922. The conspicuous markings obscure the ship’s heading.

On 1 February 1917, Germany announced a full resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, not only in the war zone around the British Isles but also across the Mediterranean and shortly afterwards – and most controversially – off the eastern coast of the United States. By this time the German U-boat fleet had swollen to over 150 modern submarines with an ocean-going capability, although only around a third could be maintained out on patrol at the same time. But this proved enough to cause chaos to the essential sea lanes that fed and supplied Britain. The Allied merchant shipping losses to submarines grew rapidly: 464,599 tons in February; 507,001 in March; a stunning 834,549 tons sunk in April. This was a catastrophic level of loss that could not be endured for long. If it carried on at this rate it would threaten not only foodstuff provision and the importation of other essential goods to Britain, but also the huge quantities of war materials and munitions required for the war being waged on the Western Front. Then, of course, there was the additional need to supply all the far-flung ‘Easterner’ campaigns in Salonika, Palestine, Mesopotamia and Italy. Although the rate of U-boat sinkings had accelerated marginally it was still well below the rate at which the German shipyards were churning out new submarines.

The Americans were incensed at the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare and almost immediately severed diplomatic relations with Imperial Germany. Britain then fanned the flames of heightened American emotions by releasing the text of an ill-judged telegram from the State Secretary for Foreign Affairs Arthur Zimmermann despatched in January 1917 to his Ambassador in Mexico.

We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavour in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

State Secretary for Foreign Affairs Arthur Zimmermann

The message was intercepted and decoded by the cryptologists of Room 40, after which the British cheerfully passed on the contents to the Americans. Their reaction was predictable. In a speech to Congress on 2 April 1917 President Woodrow Wilson used the crass offer as a battering ram to subdue any remaining anti-war elements within the United States, while also claiming the moral high ground.

With a profound sense of the solemn and even tragical character of the step I am taking and of the grave responsibilities which it involves, but in unhesitating obedience to what I deem my constitutional duty, I advise that the Congress declare the recent course of the Imperial German Government to be in fact nothing less than war against the government and people of the United States; that it formally accept the status of belligerent which has thus been thrust upon it; and that it take immediate steps not only to put the country in a more thorough state of defense but also to exert all its power and employ all its resources to bring the Government of the German Empire to terms and end the war.

President Woodrow Wilson

The United States declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. The potential addition of several American dreadnoughts to the Grand Fleet merely emphasised the hopelessness of any ideas the High Seas Fleet might have to contest openly British naval supremacy. But the Americans also brought the promise of an increased number of destroyers to fight the submarine war, while their booming shipbuilding industry would ultimately help replace lost Allied merchant tonnage. German shipping that had been trapped in American harbours on the outbreak of war was immediately confiscated, thereby changing sides overnight. And of course the Royal Navy no longer had to deal with American susceptibilities in enforcing the blockade of Germany. It was true that on land the American troops would not be able to make their presence felt until deep into the summer of 1918, but it was at sea that the Germans were trying to win the war in 1917.

As First Sea Lord at the Admiralty, Jellicoe still found himself right at the heart of events. After all the nervous tension of facing down the High Seas Fleet across the North Sea from 1914 to 1916, he now became the man responsible for devising a solution to the U-boat menace in 1917. The on–off nature of the campaign had hitherto prevented the Admiralty from developing a coherent policy, so it was reliant on a fairly random combination of ad hoc measures, including endlessly patrolling warships, minefield barrage nets, the arming of more and more merchantmen and the unpleasant ruse de guerre of the Q-ship. There was even a nod to the future with the employment of airships, aircraft and seaplanes to hunt for submarines, although efforts to bomb them from the skies were singularly unsuccessful. The most effective anti-submarine weapon currently developed was the depth charge which could be detonated by a hydrostatic pistol at the estimated depth of the intended U-boat prey. They contained some 300 pounds of high explosives, but tests had shown the British that they could not destroy a submarine unless they went off within 14 feet of it, although within 28 feet would probably cause enough damage to force the submarine to surface, where she could be swiftly dealt with by ramming or gunfire. What was needed was a method of determining with a fair degree of accuracy both the location and depth of a submarine. Yet here technology lagged well behind need, as there was still no effective way of tracking a submarine’s movements once it had submerged, except by honest guesswork. Hydrophones that could pick up the noise of the submarine propeller or engines were found to be almost useless, as all they did was indicate the likely presence of a U-boat without giving any idea of its direction or depth. Worse still, they required the ship employing them to stop still in the water, otherwise the hydrophone would merely pick up the sound of its own engines; yet stopping was clearly a risky stratagem in the presence of a U-boat.

In December 1916 the ever-methodical Jellicoe had established an Anti-Submarine Division at the Admiralty to examine and co-ordinate the British response to the threat. Unfortunately, that was as far as his inspiration seems to have taken him. Jellicoe had always been a details man, marked by an inability to delegate even mundane matters. He had coped well enough at the Grand Fleet, but at the Admiralty a combination of exhaustion and stress seem to have prevented him from discerning with sufficient speed what was, with hindsight, the obvious solution. For although Jellicoe was correct in his belief that there was no one answer to the U-boat problem, at the same time it should have been evident that a very important component of any solution would be the introduction of a convoy system as employed by Britain in times of war since time immemorial. Traditionally, vulnerable merchantmen were gathered into a convoy with an armed escort to protect them from the attentions of commerce raiders. If introduced, such a system would have at a stroke cleared the seas of helpless victims and even if a submarine had located a convoy, it would have been exposing itself to attack from the escort. But Jellicoe could see only problems. He blanched at the sheer complexity of the administrative arrangements required to organise thousands of ships into convoys, pointing to the shortage of suitable escort vessels. He also dreaded the carnage that would result should they run into a minefield; he fretted over the practical problems of maintaining convoy speed and of co-ordinating the zigzagging courses of ships of vastly different capabilities. Underneath it all he had the lurking fear that a convoy would merely gather together potential victims for an orgy of destruction should the U-boats get among them. Convoys had been successfully employed right from the start of the war for troop transports, but it was argued that they were effective because they were composed of the very finest merchantmen and liners with highly experienced crews capable of operating with military precision.

The pressure to introduce convoys continued to grow, receiving further impetus with a successful experiment for the Scandinavian trade which dramatically reduced losses. Still the arguments continued as this was just one of several major sea routes. Many at the Admiralty rejected the idea of organising all the sea routes into a comprehensive convoy system but, in the event, the losses suffered in April 1917 were such that by the end of the month it was belatedly decided to give convoys a proper trial. The US declaration of war had also eased slightly the shortage of appropriate naval escorts. The first experimental convoys began in May 1917 and proved a great success with none of the anticipated problems in station-keeping. But the introduction of a fully-fledged convoy system was very slow and shipping losses remained high throughout the summer of 1917.

Jellicoe was still swamped by the real or imagined practical difficulties of the convoy system and so felt no urgency in addressing the implementation of the policy. A dull pessimism began to colour his whole outlook on the war. This showed itself most clearly in a controversy over the measures required to destroy or render useless the German destroyer and submarine bases established in the Belgian ports of Zeebrugge and Ostend. Jellicoe had correctly pointed out the impossibility of achieving anything worthwhile using long-range naval bombardments and he had become convinced that the Army must assist in clearing the north Belgian coast before the winter of 1917 brought an end to the campaigning season. This was not so controversial in itself, but Haig would become an aghast spectator when Jellicoe made an ill-judged intervention at a meeting of the War Policy Committee on 20 June 1917. He was speaking in support of Haig’s planned Flanders offensive, but his line of reasoning went well beyond acceptable limits.

A most serious and startling situation was disclosed today. At today’s conference, Admiral Jellicoe, as First Sea Lord, stated that owing to the great shortage of shipping due to German submarines it would be impossible for Great Britain to continue the war in 1918. This was a bombshell for the Cabinet and all present. A full enquiry is to be made as to the real facts on which this opinion of the Naval Authorities is based. No one present shared Jellicoe’s view, and all seemed satisfied that the food reserves in Great Britain are adequate. Jellicoe’s words were, ‘There is no use discussing plans for next spring – we cannot go on!’

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, BEF

Haig was characteristically blunt in his overall appraisal of Jellicoe: ‘I am afraid he does not impress me – indeed, he strikes me as being an old woman!’7 Haig was being a little unfair to a great naval commander who was hampered by the effects of chronic fatigue caused by his own devoted service to his country in positions of the highest responsibility throughout the war. But, in essence, Haig was right: the diminished power of Jellicoe’s decision-making had made him a liability. Jellicoe still had the complete support of the First Lord of the Admiralty Lord Carson, but the new Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, ever the consummate politician, ‘promoted’ Carson into the War Cabinet and appointed the vigorous former industrialist Sir Eric Geddes in his stead on 20 July. The amateur naval man Geddes would in fact bring a thoroughgoing professionalism to the Admiralty, reorganising the function of the Sea Lords and the Admiralty staff to increase performance at all levels of the administration. Jellicoe was left exposed and knew that he was next in the Prime Minister’s sights.

The slow introduction of convoys was indeed a complex matter, demanding both a huge organisational effort and a steep learning curve for everyone concerned. The civilian crews of merchant navy vessels had to familiarise themselves with new working methods and accept the requirement for constant vigilance if they were not to be involved in a collision or lose touch with the convoy – especially when steaming without lights at night. Most coped better than the Admiralty had ever dreamed possible.

Convoy has added many new duties to the sum of our activities when at sea. Signals have assumed an importance in the navigation. The flutter of a single flag may set us off on a new course at any minute of the day. Failure to read a hoist correctly may result in instant collision with a sister ship. We have need of all eyes on the bridge to keep apace with the orders of the commodore. In station-keeping we are brought to the practice of a branch of seamanship with which not many of us were familiar. Steaming independently, we had only one order for the engineer when we had dropped the pilot. ‘Full speed ahead!’ we said, and rang a triple jangle of the telegraph to let the engineer on watch know that there would be no more ‘backing and filling’ – and that he could now nip into the stokehold to see to the state of the fires. Gone – our easy ways! We have now to keep close watch on the guide-ship and fret the engineer to adjustments of the speed that keep him permanently at the levers. The fires may clag and grey down through unskillful stoking – the steam go ‘back’ without warning: ever and on, he has to jump to the gaping mouth of the voice-tube, ‘Whit? Two revolutions? Ach! Ah cannae gi’ her any mair!’ but he does! Slowly perhaps, but surely, as he coaxes steam from the errant stokers, we draw ahead and regain our place in the line. No small measure of the success of convoy is built up in the engine-rooms of our mercantile fleets.

Captain David Bone, SS Cameronia