1812, 19 August: USS Constitution vs HMS Guerriere

Having broken through the British naval blockade, the 44-gun Constitution took on a 38-gun Guerriere off Nova Scotia. Within 30 minutes the American crew had crippled its smaller opponent.

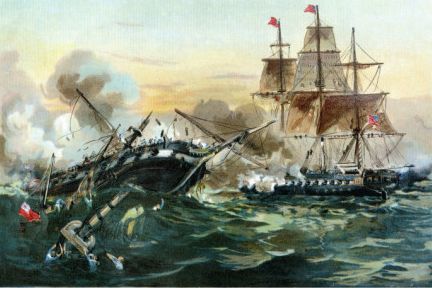

Captain Philip Bowes Vere Broke had such a well-trained crew on HMS SHANNON that he was looking for a fight with the USS CHESAPEAKE. Captain James Lawrence, formerly of the USS HORNET, was equally eager, although he and his crew were new to the CHESAPEAKE. Though rated at 38 guns, both frigates carried about 50, mostly 18-pounders. The CHESAPEAKE had a crew of 379, the SHANNON 330. On June 1, 1813, Captain Broke sent a challenge to Captain Lawrence, but Lawrence was already on the way out of Boston Harbor and did not receive it. Late in the afternoon, about 18 miles off Boston, the CHESAPEAKE—flying a large white banner reading “Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights”—came down on the SHANNON and they exchanged two broadsides. When the ships became entangled, Broke ordered boarders onto the CHESAPEAKE. With more than a third of her crew killed or wounded—including the mortally wounded Captain Lawrence, who reportedly called out “Don’t give up the ship!” as he was carried below—the CHESAPEAKE struck her colors just 15 minutes after the fight began. She became the first American frigate lost during the War of 1812. This painting of the early stage of the battle is attributed to John Schetky. © Mystic Seaport Collection, Mystic, CT, #1964.692

Though outgunned and outclassed by the Royal Navy overall, the U. S. Navy heralded the achievements of durable warships. While a few provided harbor defense along the Atlantic seaboard, others dispersed and sailed alone in search of battle with more than 1,000 vessels flying the British flag. The Navy Department concentrated maritime efforts upon building a squadron to operate on the Great Lakes, because control of the interior waters supported offensives against Canada. To the astonishment of the world, American victories in several engagements defied the dominance of the Royal Navy.

Eager to confront the Royal Navy, Commodore John Rodgers departed New York with a small squadron led by the U. S. S. President. On June 23, 1812, he encountered H. M. S. Belvidera en route to Halifax. He directed his flagship to pursue the British frigate, while exchanging a number of rounds in the first naval duel of the war. However, the Belvidera lightened its load and escaped capture. The crew on board the President sustained 22 casualties, including a wounded Rodgers. He endeavored to pursue a British convoy for weeks but eventually decided to turn south toward the Canary Islands. Departing from Halifax, British warships sailed to New York in a futile attempt to intercept Rodgers upon his return.

The British captured a U. S. brig off the shores of New Jersey, but they soon faced the U. S. S. Constitution – a wooden-hulled, three-masted heavy frigate carrying more than 44 guns. Adorned with 72 different sails, the masterful design blended speed, firepower, and durability into a warship that proved nearly unbeatable. She famously escaped from a British squadron after a 57-hour chase and defeated British warships in spectacular clashes, including two on one day. With an oak hull measuring 2 feet in thickness, the Constitution carried a large complement of heavy 24-pounder guns as well as a seasoned crew of 400 men.

On August 19, 1812, the Constitution’s commanding officer, Captain Isaac Hull, spied H. M. S. Guerriere off the coast of Nova Scotia. He pressed sail to get his vessel alongside the smaller British frigate. Holding his guns in check, he closed to 25 yards before ordering a full broadside that included cannonballs and grapeshot canisters. During repeated collisions, the Guerriere’s bowsprit became entangled with the Constitution’s rigging. When they pulled apart, the force of extraction damaged the Guerriere’s rigging. Her foremast collapsed, taking the mainmast down in a crash. In less than a half-hour, the British Commander James Dacres surrendered his wreck. The Americans sustained seven deaths in the battle, while the number of British dead reached 15. Hull freed 10 impressed Americans on board the remains of His Majesty’s ship. Moses Smith, an American seaman on board the Constitution, claimed that the British shots in the duel hit the hard plank of the wooden hull but “fell out and sank in the waters.” As a result, he shouted with his seafaring compatriots: “Huzzah! Her sides are made of iron!” The victory earned the Constitution the nickname, “Old Ironsides.”

Afterward, U. S. warships formed three squadrons to harass British convoys. Rodgers operated in the North Atlantic, while Commodore William Bainbridge and Captain Stephen Decatur commanded the other squadrons in the South Atlantic and the Azores, respectively. The operational capabilities of American-built frigates such as the Constitution and the United States surprised the experienced officers of the Royal Navy, which held a nearly flawless record in naval warfare against the French over the previous 20 years. On October 25, 1812, Decatur captured the light British frigate named H. M. S. Macedonian. Two months later, Bainbridge hammered H. M. S. Java before returning to Boston. Though encountering only a handful of ships, Americans on the high seas dared their British rivals to fight them.

After a string of stunning defeats, Great Britain finally won a duel with an American frigate on June 1, 1813. While commanding the U. S. S. Chesapeake, Captain James Lawrence met H. M. S. Shannon commanded by Captain Sir Philip Broke in full daylight. As the two vessels sailed broadside to broadside only 40 yards apart, the British gunners swept the American quarterdeck with a deadly shelling. With Lawrence mortally wounded, the Chesapeake drifted without direction into the Shannon. In the chaos of battle, the fluke of the latter’s anchor caught the former. Broke quickly boarded to claim his prize, but Lieutenant George Budd rallied the Americans below deck for a counterattack. Though fighting desperately under the banner “Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights,” their spirited resistance collapsed in only 15 minutes. The Americans reported 62 dead, while the British lost 43. In sum, the casualties on board the two ships totaled 228 men. As the victors added the Chesapeake to the Royal Navy, the forlorn Lawrence uttered his last command before expiring: “Don’t give up the ship.”

With the establishment of the North American Naval Station, the Royal Navy pressed the blockade and effectively controlled the Atlantic Coast. Nevertheless, Captain David Porter sailed the U. S. S. Essex around Cape Horn during 1813 and seized British whalers in the Pacific Ocean. Outbursts by American privateers occasionally struck British vessels, but the “militia of the sea” preferred to avoid battle while engaging in what amounted to legalized piracy. Accordingly, the commissioned sloops claimed 1,300 prizes by privateering during the war. Large numbers of volunteer seamen flocked to privateer service, which confounded naval officers attempting to man the U. S. warships.

Across the Great Lakes of North America, naval officers waged a battle in the shipyards as well as on the waves. During 1813, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry supervised the construction of an American squadron at Presque Isle on Lake Erie. He honored his fallen friend by naming one of the brigs the U. S. S. Lawrence, which flew a blue ensign with his last command in bold white letters: “Don’t give up the ship.” The brig weighed about 500 tons and carried two masts, while the 20 guns proved effective at close range. In addition to completing construction on another brig, the U. S. S. Niagara, he hastily built three schooner-rigged gunboats. By summer, he had welcomed the timely arrival of a captured brig, three schooners, and a sloop to Presque Isle Bay. Moreover, he assembled a makeshift crew from the castoffs and misfits that trickled inland from the eastern seaports. Employing an innovative system of lifts devised by Noah Brown, a shipwright, Perry and his recruits pushed the untested vessels over the sandy bar and into the lake waters that August.

On September 10, Perry’s squadron of nine sailed near Put-in-Bay to challenge a British squadron of six under Commander Robert H. Barclay. The duel on Lake Erie involved ship-to-ship broadsides, but the shifting winds gave credence to a sailor’s legend about “Perry’s luck.” Two British ships, H. M. S. Detroit and H. M. S. Queen Charlotte, raked Perry’s flagship for an hour. Under the command of Lieutenant Jesse Duncan Elliott, the Niagara remained strangely aloof. When the last gun on the Lawrence became unusable, Perry draped the blue ensign over his arm and steered a rowboat a half-mile through intense gunfire to the Niagara. Once aboard, he renewed his attack with courage and decisiveness. After Barclay’s lead vessels became entangled during a clumsy maneuver, America’s “Wilderness Commodore” poured grape, round, canister, and chain shot upon them. Hence, the entire squadron of the Royal Navy surrendered that day. The British counted 40 killed in action, while the Americans suffered 27 deaths – almost all of them aboard the Lawrence. Perry noted the outcome in a brief dispatch to U. S. forces gathered at the Sandusky, which read: “We have met the enemy, and they are ours.”

The Battle of Lake Erie marked a turning point in the war, because it gave U. S. forces control over the waterway. The heartening news about the naval duels cheered the nation, although the prize of Canada remained in British hands. Even if the Royal Navy still ruled the high seas, Perry’s ensign with Lawrence’s motto inspired generations of American midshipmen.