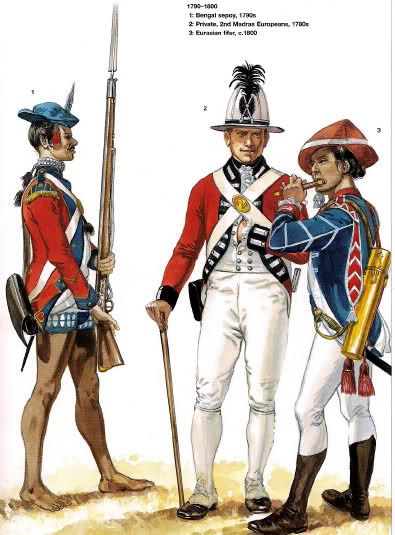

Plate by Gerry Embleton from Ospreys -“Armies of the East India Company 1750-1850”. L to R Bengal Sepoy 1790s, Private 2nd Madras Europeans 1780s & Eurasian fifer c.1800.

Plate by Gerry Embleton from Ospreys -“Armies of the East India Company 1750-1850”. Carnatic Troops c 1785 L to R Subedar, Trooper & Havildar.

In the east, the speed with which the East India Company exploited trade with Asia surprised investors and government alike. By 1690 about 13 per cent of Britain’s imports came from Asia. British merchants were also quickly opening access to China as a market. By 1720 about 10 per cent of the East India Company’s trade was with China. It is easy to forget how flimsy the foundations of the East India Company in India were. In 1713 the Company owned only a score of ‘factories’. In Calcutta – as in most other cities – there were only a few hundred Britons in each factory. In such circumstances, the Company was obliged to work with the local populations; any other strategy would not work. An attempt to be more dominant in Bengal in 1688 had led to opposition from the local population and a sharp reversal in policy.

In 1698 an attempt by other English merchants to break the East India Company’s monopoly on Asian trade by chartering a new company failed. The old East India Company simply bought the majority shareholding in the new company and restored its hugely valuable monopoly. Thereafter, any threats to its dominance of Asian trade were fought in the courts, which imposed heavy fines on incursions into the East India Company’s chartered area.

Although India is often thought of as the quintessential British imperial possession, at the end of the seventeenth century it was still an open field. The Dutch Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (from 1601) and the French Compagnie des Indes Orientales (from 1664) traded alongside the East India Company for cotton, indigo and silk. What permitted the European merchants to gain such a foothold in India were long-range trading ships with navigational and maritime skills; commerce at such a distance would have been impossible without these. The Europeans also possessed firearms, which could be used to enforce their interests. India was receptive to colonial and commercial advances because there were local merchants and producers who could supply European traders. Moreover, local rulers in India were prepared to grant concessions to the traders in exchange for customs duties or support in dynastic feuds.

The East India Company found that India possessed some of the key economic structures that facilitated trade. The subcontinent had a mobile labour force, some of which was organized in merchant guilds, and much of which could be directed to work by rulers and bureaucratic systems. India also had a well-developed financial system, including credit notes and banks. Indian merchants lent funds to rulers, and Europeans were also willing to do so. Additionally, although the Mughal Empire was in rapid decline, the British were able to adopt the systems and bureaucracy that the Mughals had establish to reinforce and sustain their control over the territories into which they expanded.

In south India, the British base in Madras was less significant than the French fort at Pondicherry. The French strength in south India was based, in part, on their intervention in Indian domestic affairs. This enabled France to capture Madras in 1746 during the War of Austrian Succession, although it was handed back to the British in 1749. In Hyderabad, in central India, similarly, France allied itself with the local ruler, the Nizam, and this led to reduced influence for the British, who were allied to the ruler of Peshwa, the Nizam’s enemy. This pattern was reversed in Carnatic, in south India, where the British support for Muhammad Ali, the successful claimant to be the Nawab of Carnatic, produced a ruler sympathetic to the East India Company in 1751.

The Seven Years War in India witnessed the rise of Robert Clive, who had come to Madras in 1744 as a ‘writer’ – a combination of clerk and accountant – for the East India Company. He had distinguished himself during the 1746 attack by the French on Madras, but depression forced him to leave India in 1748. He returned in 1755, as deputy governor of Fort St David, south of Madras. From here, he evicted the French from Hyderabad, eventually being commissioned as a colonel. During the war, the ruler of Bengal, in eastern India, had chosen to oppose the British. With impressive diplomatic and military action, he was defeated by Clive at Plassey in 1757. It was a stunning victory, in which Clive’s army, numbering just 1,100 Europeans and 2,100 sepoy troops with nine field-pieces, faced 18,000 cavalry, 50,000 infantry and fifty-three heavy guns operated by French fusiliers. Clive was victorious, largely due to the scattering of the Bengali troops. He then captured the Bengali treasury and distributed enormous sums in spoils. Clive himself gained £160,000, while £500,000 was distributed among the East India Company troops, and £24,000 was given to each member of the Company’s committee – worth several million pounds in today’s values. By the end of his career, Clive was the first self-made millionaire.

It was during this war that the Nawab of Bengal incarcerated 146 English prisoners in the ‘Black Hole of Calcutta’, from which only twenty-three emerged alive. The only eye-witness account of the ordeal of the prisoners was published in the Annual Register in 1758, which created a wave of anger in Britain, although later investigations questioned the truth of the report. Clive also defeated an opportunistic Dutch action. During the war with France, Britain was responsible for another great colonial victory, by capturing their historic base at Pondicherry in 1761.

One of the outcomes of the Seven Years War in India was British dominance over Bengal. This led to the establishment of the system whereby the East India Company troops were paid from Bengali tax revenues rather than from British taxes or Company profits. This was a blueprint for the financing of the administration of India; it was also this model that the Americans would refuse to tolerate a decade later. While British relations with America declined during the 1760s, the East India Company conducted four wars against Mysore and, after some setbacks, reached an alliance with the ruler of Delhi. But Mysore and Hyderabad, having allied themselves with France, remained a source of conflict with Britain until the end of the century, when Arthur Wellesley (1769–1852), later the Duke of Wellington, defeated the ruler of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, and brought them under British control.

The British rule in India was established through a combination of effective leadership, a policy of divide and rule between feuding dynasties in India, superior firepower, the use of mercenaries, the exploitation of Indian revenues against the country itself and the incentivization of local entrepreneurs. After 1773, when a governor general was established by the British government, the government of India gradually became better organized and less improvised.

Warren Hastings (1732–1818), the first governor general, was alert to the opportunities to expand British territory. He also was determined to plan and organize British control of the subcontinent carefully. The East India Company continued the practice of using Mughal tax collectors to raise revenue, but bribes, protection payments and corruption affected the Company’s finances. Under Hastings, tax collection was extended in south India and a Board of Revenue was established in Calcutta. The East India Company officials were merciless in their extraction of funds from India. Consequently, despite a famine in Bengal in 1769–70, the tax yield was unaffected. At the same time, the payments to princes and to the Mughal emperors were reduced and eventually stopped. In time, pensions for some princes were resumed to maintain order, and to ensure their dependence on the British.

The British gradually introduced the instruments of imperial government. In 1765 in Murshidabad, the East India Company resident established a high court to deal with disputes. By an Act of 1773 English law was established in India as the system for British subjects and their trade and commerce. Thereafter, criminal courts also gradually adopted English law. However, the British also encouraged some indigenous institutions. In 1781 Hastings supported the development of Muslim madrassas in India, with the first in Calcutta – to strengthen education for Indians.

Ironically, given Hastings’ commitment to the use of native officials to avoid exploitation, when he retired as governor general, Hastings was accused of corruption. The accusation was fuelled in part by Sir Philip Francis, whom Hasting had wounded in a duel in India. Hastings was impeached in 1788, and the trial dragged on until his acquittal in 1795. Nevertheless Hastings had enriched himself, like many others, and later writers accused him of lax principles and a hard heart towards his Indian duties.