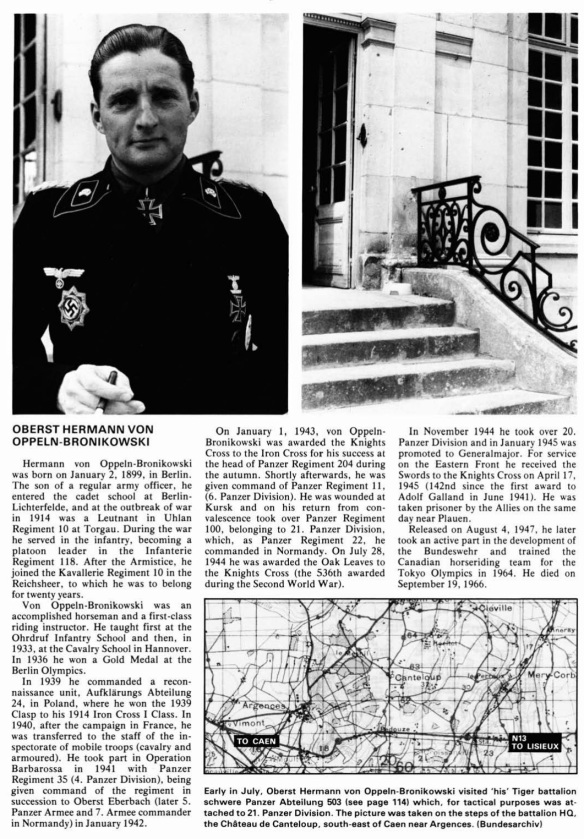

Now, 21 Panzer Division was no longer a balanced formation, capable of bringing all arms into play for mutual support; and its tank element had just arrived east of the Orne, when it was ordered to attack west of the Orne. Direction of march had to be reversed, so that the commander of Panzer Regiment 22, Oberst Oppeln Bronikowski, was now at the rear. The three tank companies rolled into Caen, but soon realised that the streets, choked with debris and fleeing civilians, were impassable. Driving at top speed, urged on by their colonel, they took the diversionary route through the industrial suburb of Colombelles, which wasted a great deal of time. Once across, they raced for the vital hills between Caen and the coast. The 25 tanks of the 1st Company and H.Q., commanded by Hauptmann Herr, reached the area between Lebisey and Biéville at about 1500; the 35 tanks of the combined and and 3rd Companies, commanded by Hauptmann von Gottberg, heading further west, reached the foot of Periers Rise at about 1600; and further west still, the armoured cars and infantry of I Battalion, Panzer Grenadier Regiment 192, were ordered by General Marcks to press on towards the coast also. The main counter-attack of 21 Panzer Division was therefore to be mounted with only three tank companies, some armoured cars, and a single infantry battalion. Worst of all, of the two dozen 88 mms of the anti-tank battalion which had been stationed on top of Périers Rise, only three were still there, the remainder having been moved by Richter.

And as the Germans moved to the foot of the heights, the British tanks, pushing on from the coast on the other side, reached the top. They were barely in position when the German attack came in. The bad weather bonus, which was the fundamental reason for the delay and confusion on the German side, had affected the British similarly. 185 Brigade Group, consisting of the tanks of Lieut.-Colonel Jim Eadie’s Staffordshire Yeomanry, the infantry of Lieut.-Colonel F. J. Maurice’s 2 K.S.L.I., and the SP guns of 7 Field Regiment R.A., should have rushed Caen at once, the infantry riding on the backs of the tanks. But, as the tanks and guns were held up by the chaos on the beaches, at 1230 hours the Shropshires shouldered their packs and started to walk there, minus their heavy weapons and vehicles, and without the tanks. The lightning punch at Caen had been reduced to a few hundred plodding riflemen.

As they climbed up the heights, they were joined by their own 6 pounder anti-tank guns, a few 17 pounders, and two squadrons of the Yeomanry. The third squadron was called up just in time to meet the attack on Biéville by Hauptmann Herr’s 25 tanks. “At first these tanks received no opposition,” runs a German account.5 “Then, as they moved up the hill, the English opened heavy defensive fire from both tanks and anti-tank guns. Their position was tactically well-chosen and their fire both heavy and accurate. The first Mark IV was blazing before a single German tank had the chance to fire a shot. The remainder moved forward, firing at where the enemy were thought to be; but the English weapons were well-concealed and within a few minutes, we had lost six tanks.” Meanwhile, sweeping round to the left of Périers Rise were the 35 tanks led by Hauptmann von Gottberg; they attacked Point 61, held by a squadron of the Staffordshires. “The position was the same. The fire of the English, from their outstandingly well-sited defence positions, was murderous. This group also was soon repelled, losing ten tanks. Within a brief space of time, the armoured regiment of 21 Panzer Division had lost a total of sixteen tanks, a decisive defeat, from which, especially in morale, it never recovered.6 The long wait in the morning, plus the diversion by Colombelles, had consumed fourteen hours and given the enemy time to build up a strong line of defence. The one and only chance on D-Day had been lost. Never again was there to be such a chance.”

Nevertheless, this brief skirmish had settled the fate of Caen. The British position was already precarious, and appeared worse than it was. There was a wide corridor to the sea on their right, the German tanks were milling about in it, and the infantry and armoured cars of I Battalion, Panzer Grenadier Regiment 192, were already driving down it. But above all, the rising ground inland of the beaches was crowned by four fortifications of the ‘West Wall’, which held out stubbornly after being over-run and raked the advancing British in the flanks. The two outlying forts, ‘Sole’ and ‘Morris’, fell at 1300 hours, but ‘Daimler’, covering the British left, held out until 1800, and ‘Hillman’, covering the British right, was only partially subdued by 2015. This latter was almost entirely underground and contained the H.Q. of Oberst Krug, commanding 736 Grenadier Regiment of 716 Infantry Division. As the main body of 185 Brigade Group moved past it, to back up the dash for Caen, its machine-guns cut down 150 men of the Norfolks. To Raymond Arthur Hill, looking up at it from, behind the sights of a Sherman’s gun, ‘Hillman’ was just a concrete dome, with British air bursts exploding ineffectually above it. Then there was a stunning explosion beside the tank, his periscope shattered, and he found himself temporarily deaf; it was a near-miss from a shell or mortar, incapable of doing more than shake the tank, but frightening the first time. Then, with other Shermans of the 13/18 Hussars, he moved up the rise and drove right on top of the dome, spraying everything in sight, and hoping to get nothing in return. Down below, in the underground galleries, bitter fighting was going on between the Germans and the Suffolks, with the pioneers using heavy explosive charges to destroy the stubborn defenders. At 2000 hours, the mechanised infantry of I Battalion, Panzer Grenadier Regiment 192, reached the sea between Lion-sur-Mer and Luc-sur-Mer, a few miles to the west, and linked up with the Germans still holding the coast there. The Hussars were pulled back from ‘Hillman’, to take up defensive positions on the skyline, and warned to expect a counter-attack from 21 Panzer Division. On the other side of the Orne, Werner Kortenhaus was with the Battle Group Luck at St. Honorine, waiting to counter-attack the weakened parachutists, and Brigadier Hill was organising his H.Q. staff at Le Mesnil as a fighting unit.

At about 2300 hours, they were all witnesses of what appeared to the Germans to be a lightning reply to 21 Panzer Division’s thrust, but was in fact the planned fly-in of 6 Airborne Division’s airlanding brigade in gliders with heavier weapons and equipment. “No one who saw it will ever forget it,” declared Kortenhaus. “Suddenly, the hollow roaring of countless aeroplanes, and then we saw them, hundreds of them, towing great gliders, filling the sky.” They came down in various landing zones, and on both sides of the Orne, some passing directly over Leutnant Höller’s anti-tank guns, still holding on at Bénouville. “An uncanny silence seemed to descend upon everything and everyone,” he recollected. “We all looked up, and there they were just above us. Noiselessly, those giant wooden boxes sailed in over our heads to land, where men and equipment came pouring out of them. We lay on our backs and fired, and fired, and fired into those gliders, until we could not work the bolts of our rifles anymore. Our 2 cm flak troop shot some down and damaged many more, but with such masses, it seemed to make little difference.” These gliders, landing apparently behind the Germans who had reached the coast, caused the immediate abandonment of the counter-attack west of the Orne; another group of gliders, landing east of the Orne, bumped down directly in the path of the Battle Group Luck, not more than 100 yards from the 17 tanks of 4th Company, Panzer Regiment 22. “It was a unique opportunity,” said Kortenhaus, “but there was a wait before the order came crackling in my earphones: Tanks advance. And then the air was alive with calls of: Eagle to all, Eagle to all, come in, please! Engines roared into life, flaps clanged shut, and we rolled in cautious tempo and attack formation towards Herouvilette. But before we had even fired a shot, darkness had fallen over the rolling tank formations, and then warning lights shot up—we were attacking positions held by our own panzer grenadiers! Baffled, the men shook their heads. Obviously, an advance into empty space. And that was all that we, a strong tank company, achieved on this decisive day.”

The gliders had barely finished landing, before part of 185 Brigade Group, the Warwickshires, came pushing into Bénouville to relieve the parachutists and take over the attack on Höller’s unit. They should have been in Caen by now, but they were only half way. First crack, they lost the Forward Observation Officer’s tank and the officer with it, so that they could not call for artillery support. The first tank Höller saw rolled into view opposite a house 60 yards away across the park, directly in front of the muzzle of one of his 75 mm SPs which was camouflaged as a bush. But the muzzle could not be depressed sufficiently, and to start up the engine would have given the game away, so they put their shoulders to the gun and rolled it forward to the slope. “The suspense was dramatic,” said Höller, “but we managed it, and without being seen, either. Then Corporal Wlceck cranked the gun handles frantically, until the muzzle bore. Meanwhile, the English commander had got out of his turret, and walked up to the house to talk to the occupants; obviously, he hoped they would tell him where we were. The end of the tank was instantaneous. As our first shell hit, the petrol and ammunition exploded with such violence that the house beside the tank collapsed in ruins. Clearly, the English still hadn’t a clue as to where we were; they fired wildly, at extreme range, and in all directions except at the ‘nearest nearness’, and under cover of the uproar, we were able to start up and get away.” They only withdrew to a safe distance for the night, cursing their lack of tank support; with only a few tanks, they felt, Bénouville and the bridges could have been taken, and there would have been something to show for their efforts.

Their bitterness must have been matched by that of Lieut.-Colonel Jim Eadie, for at dusk his leading tanks had advanced six miles from the beaches and were on the summit of the wooded hills around Lebisey, looking down at their objective, the burning town of Caen, but without infantry support. The presence of 21 Panzer’s tanks on their open right flank was the deciding factor, and they withdrew to Biéville. “Many weeks of desperate fighting were to elapse before the Regiment again stood on that high ground,” wrote a Brigade historian. Similarly, Panzer Regiment 22 were taking stock. The front had been ripped open by the British, the static positions of 716 Infantry Division taken or by-passed; there were no infantry reserves, and the tanks of the counter-attack force must dig in and hold a defensive line instead. In those few hours, the fate of Caen had been decided. Not to fall easily, but to be taken, to be ‘martyred’ or ‘murdered’, according to one’s point of view. Already, the inhabitants had guessed at part of the truth, whereas in the morning they had been innocent and naive.

“Early in the morning,” wrote a nun at the Bon Sauveur convent, “the planes had dropped tracts telling that Caen railway station, electrical depot and other buildings would be objectives for attack.” They believed it. They did not realise that, in the bitter logic of war, the best way to deny a communications centre to the enemy is to blow the buildings into the streets, and that the buildings of Caen, constructed mainly of stone blocks, were uniquely suitable for that purpose; and that to save the lives of men, often enough, men, women and children must die. “Not even the most pessimistic imagined the horrors we witnessed. At 3 p.m. there was a violent raid, killing and wounding many students and boys at St. Mary’s Seminary and School. The Holy Family Convent and School were likewise destroyed. Refugees and wounded began to pour into our convent, we made hurried preparations to convert the wings of the vacant mental homes into temporary hospitals. Just after Vespers, three vast buildings of our Mental Home were hit, with nuns and patients buried beneath the debris. The wounded became panic-stricken; they would not remain in bed, but struggled down to the basements. And to add to the poignancy of the scene, the poor mothers from the maternity home appeared, clinging to each other for support, their babies clasped in their arms, crying pitifully. We heard the screams of terror and the roar of gunfire, and above it all, a voice raised in prayer to God for protection. We could see fire bombs drop and huge buildings blazing; we could see the planes swoop down, then rise up, having done their deadly work; hear the bombs and the sound of machine-guns. At midnight, 400 nuns of the Order of Our Lady of Charity, and as many girls, sought shelter with us. Their Convent and Home had been burned, sixteen nuns had perished in the flames. Almost every convent in Caen had been hit.” The ‘power stations’ and the ‘railways’ were for the history books and the memoirs; the blood of the nuns was for reality, and a few hours delay to the Panzer divisions, which was vital but would not read well.