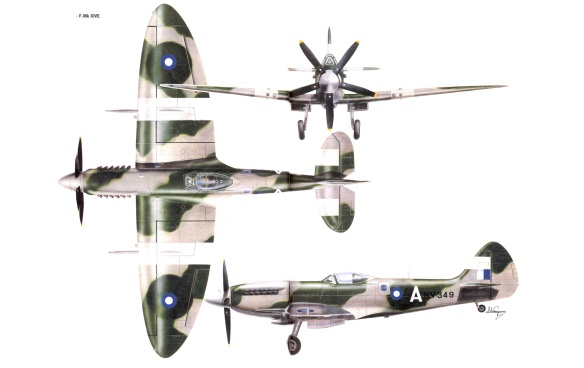

The first Griffon-powered Spitfires suffered from poor high altitude performance due to having only a single stage supercharged engine. By 1943, Rolls-Royce engineers had developed a new Griffon engine, the 61 series, with a two-stage supercharger. In the end it was a slightly modified engine, the 65 series, which was used in the Mk XIV. The resulting aircraft provided a substantial performance increase over the Mk IX. Although initially based on the Mk VIII airframe, common improvements made in aircraft produced later included the cut-back fuselage and tear-drop canopies, and the E-Type wing with improved armament.

Following combat experience the P-51D series introduced a “teardrop”, or “bubble”, canopy to rectify problems with poor visibility to the rear of the aircraft. In America, new moulding techniques had been developed to form streamlined nose transparencies for bombers. North American designed a new streamlined plexiglass canopy for the P-51B which was later developed into the teardrop shaped bubble canopy. In late 1942, the tenth production P-51B-1-NA was removed from the assembly lines. From the windshield aft the fuselage was redesigned by cutting down the rear fuselage formers to the same height as those forward of the cockpit; the new shape faired in to the vertical tail unit. A new simpler style of windscreen, with an angled bullet-resistant windscreen mounted on two flat side pieces improved the forward view while the new canopy resulted in exceptional all-round visibility. Wind tunnel tests of a wooden model confirmed that the aerodynamics were sound.

The new model Mustang also had a redesigned wing; alterations to the undercarriage up-locks and inner-door retracting mechanisms meant that there was an additional fillet added forward of each of the wheel bays, increasing the wing area and creating a distinctive “kink” at the wing root’s leading edges. Most significant was a deepening of the wing to the allow the guns to be mounted upright, resulting in a slightly reduced maximum speed compared to P-51B/C variants.

From its beginning, the Second World War appeared to be an unquestionable Axis success. Fortunately, Hitler’s military decisions combined with the geography of the Soviet Union, the Pacific Ocean, and the English Channel to give the Allies a few desperately needed advantages. For the most part, these opportunities were seized and used with considerable fighting skill until overwhelming American war production took effect. The pivotal year was 1942, with the Japanese blunted in the Pacific and Hitler’s Reich halted in Russia. Operation Torch brought Allied landings into North Africa that would threaten Europe’s belly and eventually shatter the Axis. Despite the Allied debacle at Kasserine Pass, May 1943 saw the remnants of the Afrikakorps with their backs to the sea and surrendering at Cap Bon, Tunisia. This came just five weeks after the German Sixth Army, surrounded and starving, capitulated at Stalingrad.

Italy’s king Victor Emmanuel III dismissed Mussolini in July and eventually imprisoned his former prime minister at the Campo Imperatore ski resort in Gran Sasso. A daring raid by German paratroopers freed the dictator, and he promptly declared his own Italian Social Republic in northern Italy. Americans then crossed from Sicily, landing at Anzio and slugging their way up the Italian peninsula. They’d gotten off to a rough start during Torch, largely due to incompetent leadership, but learned very quickly.

As many had foreseen, the entry of the United States into the war spelled doom for the Axis. Even without being bled white by four years of war, there was just no way to compete with the Americans. Once blooded, they rose to the occasion, as did their supporting economy, and it was an impossible combination to beat. In four years of war, shipbuilding had increased elevenfold, munitions fifteenfold; aluminum manufacturing had quadrupled, and aircraft production was twelve times greater than it had been in 1940. The USAAF had begun the war with 354,161 men and 4,477 combat aircraft. By 1944 personnel exceeded 2.3 million and the USAAF could field some 35,000 combat aircraft. A standing Wehrmacht joke went, “When we see a silver plane, it’s American. A black plane, it’s British. When we see no plane, it’s German.”

The Allied bombing campaign was largely a result of the 1943 Casablanca conference where the British and Americans mapped out the Third Reich’s destruction. Though the goal was identical, both sides were diametrically opposed on strategy. The RAF was committed to area bombing—basically the mass leveling of cities and industrial centers regardless of civilian casualties. Their firestorm method was calculated to destroy vast amounts of acreage (2,000 acres in Berlin alone) and sap German willpower. The first objective was arguably successful, but the second was not. In any event, Hamburg, Darmstadt, and a dozen other cities burned brightly under RAF bombs and eventually suffered 1.4 million civilian casualties. Of course, it also destroyed the submarine pens at Peenemunde and most of the industrial capability in the Ruhr Valley.

The Americans were convinced that only the annihilation of key military and economic chokepoints would force the Germans to their knees. To this end, they espoused the doctrine of daylight precision bombing, which would, in theory, focus immense tonnage in concentrated strikes to utterly wipe out a target. The idea had some merit in that the B-17 was the U.S. Eighth Air Force’s primary heavy bomber. Extremely tough and well-armed with ten guns, it also possessed the Norden sight, which made bombing deliveries within 135 yards from 15,000 possible. The actual CEP (circular error probable) was much higher—more than 50 percent of bombs were at least 2,000 yards off target. However, in terms of sheer volume, the damage was done.

Also, American production continued ramping up; bombers were pouring off the assembly line and there was no real shortage of planes. The concept was really put to the test on August 17, 1943, in a grand raid to destroy the German ball bearing manufacturing centers at Schweinfurt and Regensburg.

It was a disaster for the Americans. German fighter pilots obviously hadn’t read the treatise on bomber theory and were unaware that the bomber would always get through—especially tight, heavily armed formations. Weather, timing, and complex plans aside, some 350 bombers of the 1st and 4th Bombardment Wings launched that morning, but only 290 returned. Sixty heavies and more than 550 men were lost that day, with more than eighty other bombers irreparably damaged—all for no appreciable strategic results. Ball bearing production did temporarily decrease by 30 percent, but losses were quickly made up by affiliated factories.

Bearings were essential as they were used for almost any military equipment with moving parts. Bombsights, engines, weapons, communication devices, and many others were all highly dependent on these tiny steel globes to reduce friction and support loads. The giant Swedish firm SKF was the largest worldwide manufacturer of ball bearings. From Goteborg, Sweden, and Schweinfurt, Germany, it supplied 80 percent of the total European demand. There were also dozens of foreign affiliates, including the Hess-Bright Manufacturing Company in Pennsylvania, which had become SKF Philadelphia in 1919. So when the Schweinfurt plant was bombed, the shortfall was largely covered from, of all places, the United States.

In a shameful footnote to the war, more than 600,000 ball bearings per year were shipped from American ports, via Central America, to Siemens, Diesel, and scores of other Axis companies. This was often to the detriment of U.S. companies that also needed the vital little globes. Curtiss-Wright, maker of the P-40, nearly shut down for want of bearings. It was also very likely that the Swedes warned the Germans about the raid in order to protect their factory in Schweinfurt. The National City Bank of New York (later Citibank and Citicorp) funneled money back to Sweden, and business continued as usual while American boys died in the air over Germany.

The deep penetration raids produced two inescapable lessons. First, the bomber does not always get through against an intelligently defended target and a 17 percent loss rate was not sustainable, even by the United States. The second lesson was the imperative need for a long-range escort fighter.

Enter the P-51 Mustang.

Arguably the finest fighter of the Second World War, the Mustang was the apex of piston-powered warplane development. Ironically, this iconic aircraft was created not by an initiative from the American government, but rather as a response to a Royal Air Force request. In fact, the entire design and initial production were a private venture between the British government and the North American Aircraft company.

Early in 1940 the British agreed to North American’s proposal and in May signed a contract for 320 aircraft. The company, headed by James “Dutch” Kindelberger and Edgar Schmued, was new and very small, and had previously fielded only one aircraft. This meant there were no paradigms to overcome and no history of conventional solutions to fall back on. This was very apparent when the first plane rolled out on September 9, 1940, barely 102 days after the contract was signed.

In addition to being a superb engineer, Kindelberger was also a very solid businessman. He realized that a plane that could be easily mass-produced would have a tremendous advantage once the United States began its wartime expansion. The P-51 was the first aircraft to incorporate an entirely mathematical design; all the contours were derivations of geometrical shapes and could therefore be expressed algebraically. This meant all the tooling and templates were extremely precise, yet easily duplicated for mass production.

Constructed in three main sections, the aircraft could be quickly disassembled if the need arose. Manufacturing of each section would be done separately, then the components shipped for final assembly. The engine mount only required four bolts, and the motor was easily removed by line mechanics with no special equipment. Unlike the Bf 109 or Spitfire, the Mustang’s landing gear retracted inward toward the fuselage centerline. This kept more weight along the main axis and permitted nearly a 12-foot wheelbase for safe ground operations. The brakes were hydraulic and controlled via the rudder pedals.

Other significant improvements included the beautiful bubble canopy and the practical cockpit layout. Most of the vital elements, like trim tabs, coolant switches, landing gear lever, and engine controls, were located so the pilot could reach them with his left hand, since his right hand would be on the stick.

Another innovation was the deliberate design of a laminar flow wing. We know from basic aerodynamics that airflow divides over a wing, and as it splits, the change in velocity alters surface pressure to produce lift. If the flow separates past a critical point, more drag is produced than lift and the wing stalls. This can be delayed somewhat by keeping the thin boundary layer of air closest to the wing intact as long as possible. A laminar flow wing is symmetric, so the air divides evenly and flows over an extremely smooth finished surface. This considerably reduces drag while increasing lift.

One advantage to less drag is that the aircraft can be much heavier, yet still retain high performance. For the Mustang, the greater weight meant more weapons and fuel without a corresponding loss of speed or maneuverability. So high performance was preserved while range and firepower increased, thus giving the Allies a fighter capable of deep escort into the Reich. The U.S. Army had become aware of North American’s aircraft and managed to keep the production line open by ordering a ground-attack version of the RAF fighter. The USAAF purchased 310 of the newly designated P-51A fighters in August 1942, and the first one flew by early February 1943.

Though the Mustang promised to be an excellent aircraft, the Allison engine was a problem. Even with a supercharger and a larger prop, the V-1710-81 motor could only deliver 1,125 horsepower at 18,000 feet. The superb Rolls-Royce Merlin was the obvious choice for later Mustangs, but production was an issue. The British company was already heavily committed supplying the Spitfire, Hurricane, and Lancaster bombers, so an American company was needed to manufacture the engine under license. Back in 1940, Henry Ford offered to do the deal, but only for American defense—under no circumstances for Britain. Instead, Ford built five-ton trucks for the German army and his sixty-acre plant in Poissy, France, began turning out aircraft engines for the Luftwaffe.

So Packard was selected to build the 1,500-horsepower Merlin V-1650. Capable of 400 knots at 30,000 feet, the new engine had a novel two-stage supercharger that would automatically kick in around 19,000 feet. This permitted a climb rate exceeding 3,000 feet per minute, with unmatched high-altitude maneuverability. Combined with the slick laminar flow design, the Allies had a fighter aircraft that could escort bombers all the way to Austria if needed.*

Previous hard-learned lessons regarding weapon systems were also heeded in the Mustang design. The RAF version carried four .50-caliber and four .303-caliber Brownings, while the Mk IA had four Hispano 20 mm cannons. American P-51A variants mounted four .50-caliber machine guns and could carry a pair of 500-pound general purpose bombs. Both versions were equipped with new gyroscopic gunsights that compensated for bullet drop and made accurate deflection aiming possible.

Correctly regarded as the culmination of Mustang development, the Merlin-powered P-51D model began appearing in March 1944. More than eight thousand of these magnificent machines were built, and they had a profound effect on the outcome of the war against the Third Reich. Bombers could now hit factories, laboratories, and key targets deep inside Germany. Steel production and electrical generating capacity fell by 30 and 20 percent, respectively. Hundreds of French locomotives were destroyed along with railyards and repair facilities. Bridges, depots, and rolling stock were attacked to the point where the entire French transportation system was operating at only 60 percent capacity. This made logistical support to the Atlantic Wall and any type of rapid German military response problematic. The Reich’s already fragile economy steadily disintegrated.