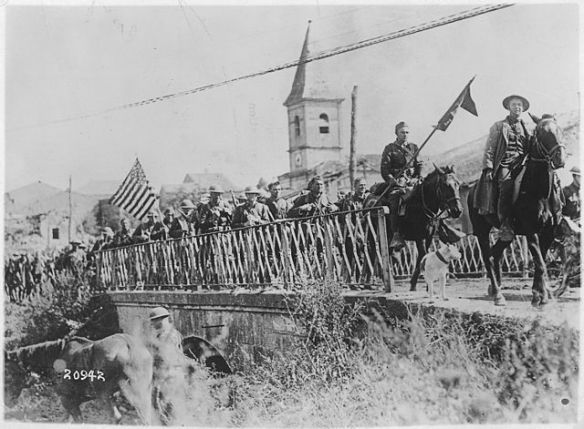

Battle of St. Mihiel-American Engineers returning from the front; tank going over the top; group photo of the 129th Machine gun Battalion, 35th Division before leaving for the front; views of headquarters of the 89th Division next to destroyed bridge; Company E, 314th Engineers, 89th Division, and making rolling barbed wire entanglements.

St. Mihiel was an American victory and celebrated as such. Once again, as at Cantigny, Château Thierry, and Belleau Wood, the AEF troops had fought hard. Indeed, the German high command took note of the Americans’ aggressive spirit. But the sense of victory from St. Mihiel must be tempered. It is generally conceded that a more experienced army would have taken a greater number of prisoners. In addition, the German army, aware of the forthcoming assault and of its vulnerability within the salient, had begun to withdraw. The fight was not as fierce as it might have been. Nonetheless, the American First Army had gone into battle and won.

Next time, at the Meuse-Argonne, the fight would be far more difficult.

Noteworthy in the attack upon the salient at St. Mihiel was the widespread use of aircraft. More than fourteen hundred airplanes took part in the operation. They were flown by American, British, and French pilots (and a few Italians). In command of this aerial armada was Colonel Billy Mitchell, who, postwar, would become a leading advocate of American airpower.

The airplane came of age in the First World War. Armies and navies alike saw opportunities in the use of aircraft. They pushed aeronautical technologies such that planes became faster, more versatile, and somewhat more reliable. They also became weapons of war. Machine guns were carried, though at first their impact was slight. But when interrupter gears were developed so that machine guns could be fired safely through spinning propellers, airplanes became deadly killing machines.

These machines were called pursuit planes, what today are termed fighters. They carried a crew of one, the pilot, and could attain speeds of up to 140 mph. In Germany and Britain, in America and France, and in other countries as well, pursuit pilots became national heroes, especially those who destroyed five enemy aircraft, thus winning the coveted (but unofficial) title of ace. Famous still today is the German ace Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. His score of eighty kills was the highest tally of any pilot in World War I. The leading American ace was Eddie Rickenbacker who, flying French-built aircraft, knocked down twenty-six German planes.

Despite the fame associated with pursuit pilots, they and their aircraft did not play a decisive role in the war. Nor did the bombers. These were larger machines, multiengine, with a crew of three or four. From 1915 on, they were heavily engaged, bombing enemy troops and installations. But the size and number of bombs they could carry were slight and the accuracy of their aim uneven. So they too played a secondary role.

However, one particular bomber is worth mentioning. This is the German Gotha G IV. Powered by two Mercedes six-cylinder engines, the airplane had a top speed of 88 mph at twelve thousand feet. More noteworthy was its range. The Gotha could fly from Ghent, Belgium, to London and back, which it did on more than one occasion. As did German zeppelins, rigid-framed airships. Together they constituted the first-ever effort at strategic bombing. Even though they killed some fifteen hundred people in England, the damage they caused was insignificant. Their principal impact was to alarm civil and military authorities, forcing both to devise appropriate defenses and, with good cause, to worry about what the future might bring.

The one function performed by aircraft during World War I that did make a difference on the battlefield was reconnaissance. Airplanes were used to locate enemy positions and to track the movement of enemy troops. In 1914–1918 these planes usually were two-seaters. Up front was the pilot. To his rear was the observer who, when the need arose, also functioned as a gunner. Often useful, observation aircraft occasionally proved decisive. In 1914, for example, they alerted Joffre to the gap opening between the German First and Second Armies as the two enemy forces approached the Marne.

Later in the war, observers would employ specially developed cameras with which to photograph the enemy. On both sides, aerial photography was extensive. Such was the extent of this activity that a principal function of pursuit planes was the destruction of enemy aircraft devoted to observation.

Another important task given to observation aircraft was spotting for artillery. The soldiers who fired the cannons needed to know where their shells were striking. Many times in the course of the war they were so informed by aircraft aloft for that very purpose.

The first Americans who fought in the sky did so as part of the French Air Service. Many of these initially served as ambulance drivers, in units supporting the French army. Indeed, as noted previously, the first Americans to see the ugly face of war transported wounded French soldiers to medical facilities in the rear. They had arrived in France well before the United States entered the war in 1917. Such was their service that 225 of them won citations of valor. No recounting of America’s involvement in the First World War is complete without reference to their work.

In April 1916, the French Air Service established a squadron of pursuit planes piloted primarily by Americans. Like the ambulance drivers, these pilots were volunteers. Eventually, thirty-eight Americans flew in this squadron that became known as the Lafayette Escadrille. With French officers in charge, the squadron flew more than three thousand sorties and downed more than fifty enemy aircraft. One of the Escadrille pilots, Raoul Lufbery, an American born in France, was an ace with seventeen victories to his credit. Once the United States entered the war, the Lafayette Escadrille ceased to exist, becoming the 103rd Aero Squadron of the American Air Service. Three months later, Lufbery was gone. He jumped (or fell) to his death from a burning aircraft. Pilots back then did not wear parachutes.

In both France and the United States, the Lafayette Escadrille won great fame, not just for its exploits in combat, or because its mascots were two cute lion cubs named Whiskey and Soda. The squadron gained prominence because it represented the desire of many Americans to aid France in that country’s hour of need. As time passed and the war continued, more Americans joined the French air corps, many serving with distinction. Today, David Putnam, Frank Baylies, and Thomas Cassady are names no longer remembered. But each flew for France to the regret of more than a few German aviators.

American pilots also flew in British squadrons, even after the AEF arrived in Europe. Forty-one of them scored five kills or more. Among these aces were two brothers from New York, August and Paul Iaccaci. Both flew in No. 48 Squadron of the Royal Air Force, and remarkably, both downed seventeen aircraft. Another of the American pilots in British service was Howard Burdick. He flew the Sopwith Camel, considered by many to be the best of the Allied pursuit planes. Burdick downed six enemy aircraft in September and October of 1918. Years later, during the Second World War, his son Clinton destroyed nine German planes while piloting a P-51 Mustang of the American Eighth Air Force.

In both Great Britain and America, in France and Germany, pursuit pilots were considered to be men of dash and daring, knights of the sky who bravely confronted the enemy in airborne chariots. Less attention was given to their victims, of whom there were many. The top eight French aces of World War I, for example, killed at least 339 German flyers. These men joined 7,873 others of the Kaiser’s air service who did not survive the war. Britain’s Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service, combined in 1918 to form the Royal Air Force, counted 9,378 men who died in their aerial operations. Many of these were boys of nineteen or twenty whose flying skills were limited. Due to the demand for pilots they had been rushed into battle. Needless to say, their chances of survival were slim.

The United States had but 237 flyers killed in combat (one of the dead was Quentin Roosevelt, youngest son of Theodore Roosevelt). The number is relatively small, reflecting the limited time the AEF spent at the front. Nonetheless, America’s Army Air Service performed extremely well. Its pursuit pilots accounted for the destruction of 781 enemy aircraft, losing 289. As the United States produced no combat planes of its own, American pilots flew machines designed and built in Britain and France. The latter included both the Nieuport 17 and the SPAD XIII, two aircraft the Americans used to good advantage.

Frank Luke was one of these pilots. He flew the SPAD XIII, a fine machine that by war’s end equipped most U.S. Air Service units. SPAD was the acronym for the French company that produced the airplane: Societe Pour L’Aviation et ses Derives. From Arizona, Luke destroyed eighteen enemy machines. In September 1918 he was shot down by ground fire. His SPAD crashed in enemy territory. Wounded, but still very much alive, Frank Luke drew his pistol and fired at the Germans. They fired back and killed him. Today, Luke Air Force Base in Arizona honors his fighting spirit.

Several of the enemy machines Frank Luke destroyed were observation balloons. Tethered to the ground, these reached heights of up to five thousand feet. With a crew, usually two men, balloons were employed by both sides to monitor the enemy’s whereabouts. Filled with gas, often hydrogen, balloons were frequent targets of pursuit planes. But they were not easy to bring down. At their base were numerous antiaircraft guns just waiting for enemy aircraft to appear. This made attacking observation balloons a hazardous venture. Manning them also was dangerous. When struck by incendiary bullets, the balloons burst into flames, creating a spectacular fireball. However, unlike pursuit pilots, balloon crews were issued parachutes. The crew’s challenge was to jump neither too soon nor too late.

Observation balloons were in full use when British, French, and American armies began the great offensive that, at last, would bring about the end of the war. Many in leadership positions in both France and Britain thought the war would continue well into 1919. Not Foch. He believed that a massive attack across the entire Western Front in September would crush the German army. After all, he reasoned, the Allies outmatched their enemy in soldiers, supplies, tanks, and aircraft. Accordingly, the Supreme Commander drew up a plan of battle that was complex in detail yet simple in concept: the British (and the Belgians) would strike in the north, and the French would advance in the middle, while the Americans would attack in the south, in the area known as the Meuse-Argonne. With characteristic energy, Ferdinand Foch proclaimed, “Tout le monde a la bataille.”

The Meuse is a major river, 575 miles long, that flows from northeastern France through Verdun into Belgium and Holland, eventually draining into the North Sea. The Argonne is a region of France, much of it heavily wooded, east of Paris, through which the Meuse flows. In 1918, the area was well fortified by the German army.

The assault by Pershing’s army began on September 26 with an artillery barrage purposefully kept brief in order to maintain surprise (one of the artillery batteries was captained by a young officer from Missouri by the name of Harry S. Truman). Nineteen divisions took part, six of them French. That meant that Black Jack commanded more than 1.2 million soldiers. The campaign lasted forty-seven days and was hard fought. One German officer wrote, “The Americans are here. We can kill them but not stop them.” Throughout the battle the AEF’s inexperience showed. At times supplies ran short and tactics were flawed. Transportation was chaotic. Yet Pershing drove his men forward, relieving commanders he considered insufficiently aggressive. Many Americans fought tenaciously. A few did not. Among the former were the Black Rattlers of the 369th Infantry Regiment, an African-American unit previously mentioned. When the American attack stalled, Foch proposed to insert additional French troops into the sector and turn overall command over to a French general. Pershing refused and simply continued the assault. By early November, his troops had thrown the Germans back. In the process the AEF had inflicted some one hundred thousand casualties on the enemy and taken twenty-six thousand prisoners. American historian Edward G. Lengel says that the French army could not have done what the Americans accomplished.

Lengel also says that the British army could have and would have done so with fewer casualties, for the losses of the American army at the Meuse-Argonne were high. The American dead numbered 26,277. The number of American wounded totaled 95,923. Writes Lengel in his 2008 book on the Meuse-Argonne campaign, “Many doughboys died unnecessarily because of foolishly brave officers who led their men head-on against enemy machine guns.” Casualties aside, the Americans clearly had gained a victory. Pershing’s men had battled a German army and won.

However, one noted British military historian calls the Meuse-Argonne campaign unnecessary. In his book on World War I, H. P. Willmott writes that the battle should not have been fought at all. Why? Because to the north, British armies had breached the Hindenburg Line.

As did Foch, Sir Douglas believed the war need not continue into 1919. He thought a strong Allied push in September and October would bring the war to a successful conclusion. By then Haig commanded five field armies. Together they represented the most capable military force in the world.

On September 27 the British attacked. The assault began with a huge artillery barrage, with one gun for every three yards of territory to be attacked. Thirty-three divisions took part, two of them American. The British forces smashed into their German opponents, delivering a blow from which their enemy could not recover.

For Ludendorff and Hindenburg, September brought additional bad news. As American, French, and British troops gained success on the Western Front, an Allied army composed of British, French, and Serbian soldiers, all under the command of French general Franchet d’Esperey, advanced from Salonika in Greece into Serbia and Bulgaria. The latter was an important ally of Germany. It was a land bridge to the Ottomans and gave Germany a position of strength in the Balkans. The Allied army met with such success that Bulgaria withdrew from the war.

The Ottoman Empire too was in trouble. In Palestine, British forces were defeating the Turks, while along the southern Alps, the Italians at long last were gaining ground against the Austrians.

Everywhere Ludendorff and Hindenburg looked they saw defeat. Inside Germany the news was equally grim. In cities across the country shortages of coal, soap, and food caused ordinary Germans to be cold, dirty, and hungry. In Berlin, such shortages and the lack of military success brought about rioting in the streets. In fact, the German Imperial State was disintegrating. Both political moderates and right-wingers feared a Bolshevik-style revolution. In Kiel and Wilhelmshaven, German admirals ordered the High Seas Fleet to sortie for one last glorious battle, but its sailors said they’d rather not and mutinied. The navy thus imploded, while the army high command concluded that the war could not be won. On October 1 Ludendorff told the German foreign minister to seek an immediate armistice. Days later Hindenburg conveyed a note to the new chancellor, Prince Max of Baden, that called the situation acute. Earlier, on September 29, the two generals, the most senior in the army, had told the Kaiser the fighting had to stop.

There followed an attempt by the German government to seek an armistice through the good offices of America’s president. Prince Max and others assumed that Germany could secure a better deal were the terms first worked out with the Americans. After all, in January 1918, in a speech to Congress, Wilson—a true idealist—had outlined fourteen points that he thought should serve as the basis for constructing the postwar world. However, Wilson’s response surprised the Germans. Angered by the harm he believed German militarism had inflicted on the world and by Germany’s continuation of unrestricted submarine warfare, Wilson held firm. His terms were tough. Among them was the requirement that the Kaiser had to go. Regarding an end to the fighting, President Wilson told the Germans to speak with Foch.

In early November, with the concurrence of the Kaiser’s army, Prince Max sent emissaries to the Allied Supreme Commander. They were to discuss terms for an armistice.