Bulgaria’s borders during the first kingdom, 681-1018.

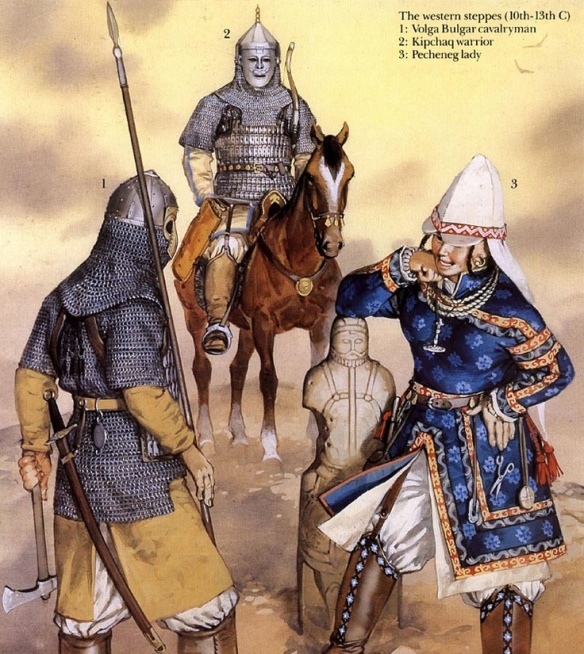

The Bulgars originated as a combination of Utigur and Kutrigur Hunnic remnants combined with Sabirs and Onogur. They were conquered by the Avars in 558 AD but cast off Avar rule in 631 AD and formed the new united khanate of Great Bulgaria around the Sea of Azov. After their defeat by the Khazars around 675 AD, some of them fled up the river Volga and formed the “Volga Bulgar” state. Most of them fled to the Danube basin where they drove the Avars westward and founded an empire which rivalled the Byzantines and lasted until 1018 AD. They relied heavily on Slav subject infantry. Their cavalry had small round shields and lances and were said to have had vertically striped trousers in red, white and blue. King Krum incorporated former Byzantine thematics into his army.

By the fourth century Roman power was weakening. Internal problems were compounded when tribes from the Asiatic steppes raided the north-east of the Balkans. In the following century ultimately fatal damage was inflicted on the Roman body politic by a series of such invaders who included the Alani, the Goths and the Huns, all of whom were enticed by the prospect of looting the fabled wealth of Byzantium. They failed in that aspiration and soon moved out of the Balkans in search of fresh plunder, but if these invaders were transient, the Slavs who also first appeared in the fifth century, were not. They were settlers. They colonised areas of the eastern Balkans and in the seventh century other Slav tribes combined with the Proto-Bulgars, a group of Turkic origin, to launch a fresh assault into the Balkans. The Proto-Bulgars originated in the area between the Urals and the Volga and were a pot-pourri of various ethnic elements, the word Bulgar being derived from a Turkic verb meaning `to mix’. What differentiated the Proto-Bulgars from the Slavs was that they had, in addition to a formidable military reputation, a highly developed sense of political cohesion and organisation. In 680 their leader, Khan Asparukh, led an army across the Danube and in the following year established his capital at Pliska near what is now Shumen. A Bulgarian state had appeared in the Balkans.

#

After its foundation in 681 the new state enjoyed almost a century of growth. Initial tensions with Byzantium were contained and regulated in a treaty of 716 which awarded northern Thrace to Bulgaria and was unusual in the mediaeval era in that it contained purely economic clauses. Immediately after the treaty the Bulgarian state assisted Byzantium in the latter’s conflict with the Arabs in Asia Minor. By the middle of the eighth century part of the Morava valley had been added to Bulgaria which then included much of what is now southern Romania and parts of present-day Ukraine.

By this time the Black Sea was a virtual Byzantine lake, and in this sector it went virtually unchallenged by Bulgaria because Bulgaria never developed a sizeable sea-going force. Even if the strategic need for a such a force had been recognised it is doubtful if anything effective could have been done to act upon that need; the Bulgarian state had a relatively low technological base and the degree of planning and coordination needed to produce a navy would have been difficult to achieve in an economy which did not even mint its own coins, preferring instead to rely on Byzantine currency.

The lack of a navy ruled out expansion along the Black Sea coast either to the north or the south, just as the chaos of the steppe area made impossible any territorial gains to the north-east; the natural direction of movement for the Bulgarian state was therefore to the north-west and the south-west. In the north-west the collapse of the Avar kingdom created a vacuum into which Bulgaria’s rulers gladly advanced, this taking their frontier up to the river Tisza; Transylvania too became part of Bulgaria. Expansion to the south and south-west was not so easy. Some of Macedonia had been taken late in the eighth century but only at the cost of losing part of Bulgaria’s possessions in Thrace. Khan Krum (803-14) determined to remedy this. In 811 he took the recently fortified Sredets (now Sofia) from the Byzantines, went on to seize Nesebûr on the Black Sea coast, and then marched as far as the walls of Byzantium itself. This was a characteristically vicious war in which, in 811, the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus became the first of his rank for almost five hundred years to lose his life on the battlefield; Krum encrusted his deceased enemy’s skull in silver and used it as a drinking goblet.

In 814 his successor, Khan Omurtag (814-31), concluded a peace which gave Bulgaria some territory in the Tundja valley, and later in his reign he was able to add Belgrade (Singidunum) and its surrounding district to his kingdom. In the second quarter of the ninth century Bulgaria, taking advantage of Byzantium’s preoccupations with the iconoclast controversy and with threats to its power in Asia Minor, expanded into Macedonia, a predominantly Slav area which welcomed this alternative to Greek, Byzantine domination. By the middle of the century Ohrid and Prespa were incorporated into Bulgaria as was much of southern Albania; Byzantine power in Europe was now confined to western Albania, Greece, the southern Vardar valley and Thrace.

Omurtag, however, was not merely a warrior. He continued Krum’s work in introducing a proper legal system into Bulgaria and he was an avid builder, his most notable achievement in this regard being the reconstruction of Pliska after the city had been burnt in 811. There are more extant inscriptions to Omurtag than to any other mediaeval Bulgarian ruler.