As the reconnaissance and artillery observation aircraft of both sides became increasingly effective in fulfilling their functions, it became ever more important to thwart them. The simplest expedient was to shoot them down and both sides developed the use of anti-aircraft guns. They too were at a fairly primitive stage of evolution and best practice consisted of little more than guessing the altitude and firing a shrapnel shell timed to burst where the aircraft would be by the time the shell got there. But as anti-aircraft gunners gained experience they became more accurate and the pilots had to take evasive action. Scout aircraft were also developed to shoot down enemy aeroplanes. The first really effective scout was the German Fokker E III monoplane. Fitted with a synchronised machine gun firing through the span of the propeller, it began to play an important role: not just in shooting down or protecting reconnaissance or artillery observation aircraft, but also in shooting down opposing Allied scouts. The Fokker scourge may have been largely a fixation of newspaper headlines, but the imminent Somme Offensive made it essential that the RFC shake off any residual fears; in this it was greatly assisted by a new generation of aircraft that could compete on equal terms with the Fokker. The first was the FE2 B, a two-seater ‘pusher’ aircraft in which the gunner perched precariously in a front nacelle seat armed with Lewis guns. It proved a sturdy and combative aircraft which, by flying in formation and acting in concert, could keep at bay the marginally superior Fokker. The FE2 B pilots found that the best method of defence was to circle round to protect each other’s vulnerable tail from the lurking Fokkers. The second new British aircraft was the DH2, a single-seater ‘pusher’ fighter armed with just one Lewis gun fixed in front of the pilot. The DH2 became an effective scout, preying on German reconnaissance aircraft and meeting the Fokkers head on. A further valuable multi-purpose aircraft was the Sopwith 1½ Strutter, a two-seater tractor biplane with a synchronised Vickers machine gun firing through the propeller. The final piece in the jigsaw was the single-seater Nieuport 16 Scout provided by the French, which, with a speed of up to 110 miles per hour, was both more manoeuvrable and faster than the Fokker, although it was only armed with a Lewis gun fixed on the top wing and firing over the propeller. With these new types to counter the Fokker scourge, the threat gradually evaporated leaving the British corps aircraft – largely variants of the BE2 C – to carry out their vital role. In all the RFC amassed 185 aircraft (76 scouts) in the Somme area, plus other aircraft flying on bombing missions. The German Air Force had only 129 aircraft (19 scouts). The Germans were soon struggling. Their first great ace, Max Immelmann, was killed in combat with FE2 Bs, and the other best known German Fokker ace, Oswald Boelcke, was promptly removed from the line. Soon the Germans were near helpless in the air, which therefore left them vulnerable on the ground.

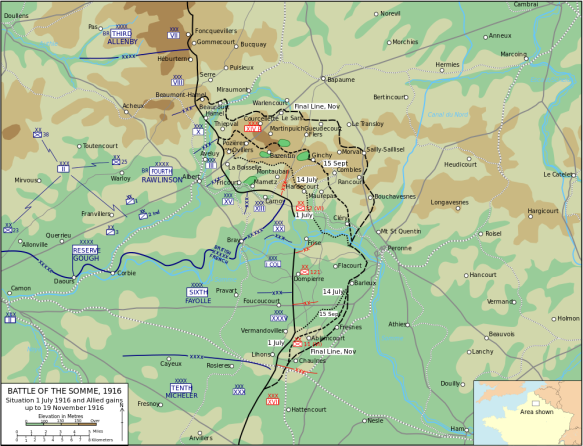

All this effort was in aid of the guns: the photographic reconnaissance enabled them to identify targets; the artillery observation helped them to destroy them. The preliminary barrage intended to harvest all the grafting work of the RFC commenced with the roar of hundreds of guns on 24 June 1916. The bombardment was intended to last for five days, but overcast weather hampered the crucial work of the RFC and there was a two-day postponement. The final date of the assault was 1 July 1916. From the British perspective the barrage seemed devastating.

Armageddon started today and we are right in the thick of it. There is such a row going on I absolutely can’t hear myself think! Day and night and all day and all night, guns and nothing but guns – and the shattering clang of bursting high explosives. This is the great offensive, the long looked for ‘Big Push’, and the whole course of the war will be settled in the next ten days – some time to be living in. I get a wonderful view from my observing station and in front of me and right and left, as far as I can see, there is nothing but bursting shells. It’s a weird sight, not a living soul or beast, but countless puffs of smoke, from the white fleecy ball of the field gun shrapnel to the dense greasy pall of the heavy howitzer HE. It’s quite funny to think that in London life is going on just as usual and no one even knows this show has started – while out here at least seven different kinds of Hell are rampant.

Captain Cuthbert Lawson, 369th Battery 15th Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery

At first some of the German garrison looked upon the barrage as little more than a minor inconvenience.

A storm of artillery broke with a crash along the entire line. As far as the eye could see clouds of shrapnel filled the sky, like dust blown on the wind. The bursts were constantly renewed and, toil as it might, the morning breeze could not sweep the sky clear. All around there was howling, snarling and hissing. With a sharp ringing sound, the death-dealing shells burst, spewing their leaden fragments against our line. The balls fell like hail on the roofs of the half-destroyed villages, whistled through the branches of the still green trees and beat down hard on the parched ground, whipping up small clouds of smoke and dust from the earth. Large calibre shells droned through the air like giant bumblebees, crashing, smashing and boring down into the earth. Occasionally small calibre high explosive shells broke the pattern. What was it? The men of the trench garrison pricked up their ears in collective astonishment. Had the Tommies gone off their heads? Did they believe that they could wear us down with shrapnel? We, who had dug ourselves deep into the earth? The very thought made the infantry smile.

Lieutenant M. Gerster, 119th Reserve Infantry Regiment

Any such insouciant attitudes did not survive long as the constant barrage wore away at their defences, slowly eroding their numbers and severely testing their morale. Although the shrapnel shells had little effect on the front line trenches, the ever-increasing deluge of trench mortar shells caused severe damage and tested the resilience of the defenders.

Of course seven days of drum fire had not left the defenders untouched. The feeling of powerlessness against this storm of steel depressed even the strongest. Despite all efforts, the rations were inadequate. The uninterrupted high state of readiness, which had to be maintained because of the entire situation, as well as the frequent gas attacks, hindered the troops from getting the sleep that they needed because of the nerve-shattering artillery fire. Tired and indifferent to everything, the troops sat it out on wooden benches or lay on the hard metal beds, staring into the darkness when the tallow lights were extinguished by the overpressure of the explosions. Nobody had washed for days. Black stubble stood out on the pale haggard faces, whilst the eyes of some flashed strangely as though they had looked beyond the portals of the other side. Some trembled when the sound of death roared around the underground protected places. Whose heart was not in his mouth at times during this appalling storm of steel? All longed for an end to it one way or the other. All were seized by a deep bitterness at the inhuman machine of destruction which hammered endlessly. A searing rage against the enemy burned in their minds.

Lieutenant M. Gerster, 119th Reserve Infantry Regiment

Gerster and his men would get their chance for revenge at 07.30 on 1 July 1916.

The final reports from the front that filtered back to the British High Command were generally positive in tone. Overall the visual impression of the barrage proved far more devastating than the truth on the ground. British progress had been more than discounted by German improvements in their defences. But that was not known at the time on the British side of the wire. In any case, they had no choice; the offensive had to go ahead as the future of the alliance with France depended on it. In the last few hours as Haig’s men prepared for the ordeal, many wrote their sad last letters home. One was so beautifully expressed that it exemplifies the feelings of men trapped and tormented by the conflicting calls of country and family.

I must not allow myself to dwell on the personal – there is no room for it here. Also it is demoralising. But I do not want to die. Not that I mind for myself. If it be that I am to go, I am ready. But the thought that I may never see you or our darling baby again turns my bowels to water. I cannot think of it with even the semblance of equanimity. My one consolation is the happiness that has been ours. Also my conscience is clear that I have always tried to make life a joy to you. I know at least that if I go you will not want. That is something. But it is the thought that we may be cut off from one another which is so terrible and that our babe may grow up without my knowing her and without her knowing me. It is difficult to face. And I know your life without me would be a dull blank. Yet you must never let it become wholly so. For to you will be left the greatest charge in all the world: the upbringing of our baby. God bless that child, she is the hope of life to me. My darling, au revoir. It may well be that you will only have to read these lines as ones of passing interest. On the other hand, they may well be my last message to you. If they are, know through all your life that I loved you and baby with all my heart and soul, that you two sweet things were just all the world to me. I pray God I may do my duty, for I know, whatever that may entail, you would not have it otherwise.

Captain Charles May, 22nd Manchester Regiment

Charles May, the loving husband of Bessie May and father to his baby Pauline, would indeed be killed the next day. He is buried in the Danzig Alley British Cemetery. Small-scale tragedies litter the history of war: sad reminders that the necessities of war ruin the lives of millions.