Date September 20(?), 480 BCE

Location Bay of Salamis off Athens, Greece

Opponents Athens and allied Greek states versus Persia

Commanders Greeks Themistocles Persians King Xerxes I of Persia

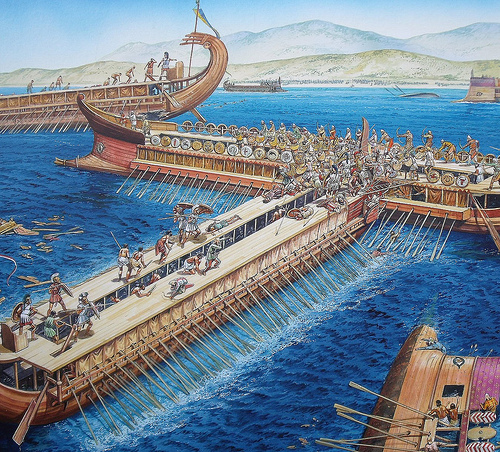

Approx. # Ships Greeks 310 triremes Persians 500 triremes

Importance Ends the year’s campaign and assures survival of Greek independence

The Battle of Salamis was the most important naval engagement of the Greco- Persian Wars. When news came of the Greek defeat at Thermopylae, the remaining Greek triremes sailed south to Salamis to provide security for the city of Athens. With no barrier remaining between Athens and the Persian land force, the proclamation was made that every Athenian should save his family as best he could. Some citizens fled to Salamis or the Peloponnese, and some men joined the crews of the returning triremes. When Xerxes and his army arrived at Athens the city was devoid of civilians, although some troops remained to stage a defense (largely symbolic) of the Acropolis. The Persians soon secured it and destroyed it by fire.

Xerxes now had to contend with the remaining Greek ships. He would have to destroy them or at least leave a sufficiently large force to contain Themistocles’ ships before he could force the Peloponnese and end the Greek campaign. Everything suggested the former, for if Xerxes left the Greek force behind, his ships remained vulnerable to a flanking attack. On August 29 the Persian fleet of perhaps 500 ships appeared off Phaleron Bay, east of the Salamis Channel, and entered the Bay of Salamis.

The Greeks had added the reserve fleet at Salamis. Triremes from other states joined, giving them about 100 additional ships. The combined fleet at Salamis was thus actually larger than it had been at Artemisim: about 310 ships.

Xerxes and his admirals did not wish to fight the Greek fleet in the narrow waters of the Salamis Channel, and for about two weeks the Persians busied themselves constructing causeways across the channel so that they might take the island without having to engage the Greek ships. Salamis then contained most of the remaining Athenian population and government officials, and the Persians reasoned that their capture would bring the fleet’s surrender. Massed Greek archers, however, gave the workers such trouble that the Persians abandoned the effort.

On September 16 or 17 Xerxes met with his generals and chief advisers at Phalerum. Herodotus tells us that all except Queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus, the commander of its squadron in the Persian fleet, favored engaging the Greek fleet in a pitched battle. Xerxes then brought advance elements of his fleet from Phalerum, off Salamis. He also put part of his vast army in motion toward the Peloponnese in the hope that this action would cause the Greeks of that region to order their ships from the main Greek fleet to return home, allowing him to destroy them at his leisure. Failing that, Xerxes sought a battle in the open waters of the Saronic Gulf (Gulf of Aegina) that forms part of the Aegean Sea. There his superior numbers would have the advantage.

Themistocles wanted a battle in the Bay of Salamis. Drawing on the lessons of the Battle of Artemisium, he pointed out that a fight in close conditions would be to the advantage of the better-disciplined Greeks. With his captains in an uproar at this and with the likely possibility that the Peloponnesian ships would bolt from the coalition, Themistocles resorted to one of the most famous stratagems in all military history. Before dawn on September 19 he sent a trusted slave, an Asiatic Greek named Sicinnus, to the Persians with a letter informing Xerxes that Themistocles had changed sides. Themistocles gave no reason for this decision but said that he now sought a Persian victory. The Greeks, he said, were bitterly divided and would offer little resistance; indeed, there would be pro-Persian factions fighting the remainder. Furthermore, Themistocles claimed, elements of the fleet intended to sail away during the next night and link up with Greek land forces defending the Peloponnese. The Persians could prevent this only by not letting the Greeks escape. This letter contained much truth and was, after all, what Xerxes wanted to hear. It did not tell Xerxes what Themistocles wanted him to do: engage the Greek ships in the narrows.

Xerxes, not wishing to lose the opportunity, acted swiftly. He ordered Persian squadrons patrolling off Salamis to block all possible Greek escape routes while the main fleet came into position that night. The Persians held their stations all night waiting for the Greek breakout. Themistocles was counting on Xerxes’ vanity. As Themistocles expected, the Persian king chose not to break off the operation that he had begun.

The Greeks then stood out to meet the Persians. Xerxes, seated on a throne at the foot of nearby Mount Aegaleus on the Attic shore across from Salamis, watched the action. Early on the morning of September 20 the entire Persian fleet went on the attack, moving up the Salamis Channel in a crowded mile-wide front that precluded any organized withdrawal should that prove necessary. The details of the actual battle are obscure, but the superior tactics and seamanship of the Greeks allowed them to take the Persians in the flank. The confusion of minds, languages, and too many ships in narrow waters combined to decide the issue in favor of the Greeks.

The Persians, according to one account, lost some 200 ships, while the defenders lost only 40. However, few of the Greeks, even from the lost ships, died; they were for the most part excellent swimmers and swam to shore when their ships floundered. The Greeks feared that the Persians might renew the attack but awoke the next day to find the Persian ships gone. Xerxes had ordered them to the Hellespont to protect the bridge there.

The Battle of Salamis meant the end of the year’s campaign. Xerxes left two-thirds of his forces in garrison in central and northern Greece and marched the remainder to Sardis. A large number died of pestilence and dysentery on the way. The Greco-Persian Wars concluded a year later in the Battle of Plataea and the Battle of Mycale.

References Green, Peter. The Greco-Persian Wars. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. Herodotus. The History of Herodotus. Edited by Manuel Komroff. Translated by George Rawlinson. New York: Tudor Publishing, 1956. Nelson, Richard B. The Battle of Salamis. London: William Luscombe, 1975. Strauss, Barry. The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter That Saved Greece-and Western Civilization. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004.