Interestingly, perhaps the greatest changes in surface warship design came about because of Soviet developments in naval weaponry. Lacking the resources to build aircraft carriers during the Cold War’s early years, the Soviet Union focused on developing long-range antiship missiles (ASMs) as well as SAMs for its ships. Thus, the Soviets introduced the world’s first operational guided surface-launched antiship missile (SASM) into service aboard the destroyer Bedoviy in 1961. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) designated the ship as a Kilden-class DDG (guided missile destroyer). Its P-1 Strela Shchuka-A (NATO designation, SS-N-1 Scrubber) cruise missile with a nuclear warhead had a range of more than 90 nautical miles (NM), far beyond the Bedoviy’s onboard radars and other sensors. The missile system’s weight also affected the ship’s handling capabilities and stability.

The Soviets then developed a smaller and shorter-ranged missile, the now famous SS-N-2 that NATO designated the Styx missile. Entering service in 1962, the Styx, with a range of 30 NM, equipped small coastal attack boats not much larger than the American PT boats of World War II. The much longer-ranged (300 NM) SS-N-3 also entered service that year when the Soviet Union’s first Kynda-class cruiser entered service. As with the Kilden class DDG, however, the Kynda’s command-guided missiles far outranged the ship’s sensors. To support a long-range engagement, the ship required an aircraft to remain within radar range of the target and provide its location to the ship throughout the engagement. For a reconnaissance or targeting aircraft to survive an engagement that close to the carrier seemed improbable in wartime. As a result, the Soviet Union focused on starting and winning the war with the first shot: finding and targeting the aircraft carrier and then launching the attack during the war’s early minutes.

Soviet technology and tactics had a profound effect on the U. S. Navy’s tactical thinking and ship designs into the 1990s.

The United States had studied surface-to-surface missiles during the 1950s but abandoned them due to funding issues. It was hard to justify put ting surface-to-surface missiles on surface ships after investing billions in aircraft carriers, aircraft, and SAM systems. Developing a guidance system for a surface-to-surface missile such as the then-existing Regulus missile did not seem cost-effective. More importantly, battleships and cruisers were the only units large enough to carry them. With their resources focused on aircraft carrier, aviation, and submarine technology, the West abandoned development of surface-launched antiship missiles in 1956. It was a mistake that would prove costly and embarrassing in the Cold War’s third decade.

Secure in the belief that the carriers would always be there, Western intelligence agencies largely ignored the Soviet antiship missile threat. During the Vietnam War, since U. S. naval aircraft had destroyed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam’s (DRV, North Vietnam) missile patrol boat force, these craft were not considered a serious problem. Certainly, they were not seen as a threat that warranted new solutions. All that changed on 21 October 1967, when a Soviet-supplied Egyptian missile patrol boat sank the Israeli destroyer Eilat with a single Styx missile without even leaving port. Fast coastal attack craft could no longer be taken lightly. One hit was enough to cripple, if not destroy, a $100 million unarmored warship.

The United States and France reacted swiftly, introducing high-priority programs to develop new missiles specifically designed to take out ships. The United States went a step further, developing long-range surveillance and targeting systems to support over-the-horizon engagements. Some were satellite-based, some were installed on ships, and others were installed on submarines and aircraft. All navies began to develop electronic and infrared detection and countermeasures systems to defeat these missiles’ terminal guidance. Electronic warfare now encompassed more than the need to defeat an enemy’s air defense systems. By 1972, a ship’s electronic warfare capabilities were as critical to the ship’s survival as its weapons systems.

These developments occurred parallel to the U. S. Navy’s development of a global naval monitoring system driven by the Soviet Navy’s first worldwide naval exercise, OKEAN-70, and the introduction of the first exercises demonstrating its first-shot tactics. The resulting Ocean Surveillance Information System (OSIS) entered service in 1972. By the late 1970s, OSIS had taken on the additional mission of supporting rapid over-the-horizon targeting by U. S. Navy and NATO missile-equipped ships. Although the Soviets never developed a similar global oceanic monitoring capability, they did develop an extensive array of electronic air- and space-based targeting systems to support their naval units. Both sides developed increasingly complex and long-ranged antiship, air defense, and surveillance systems.

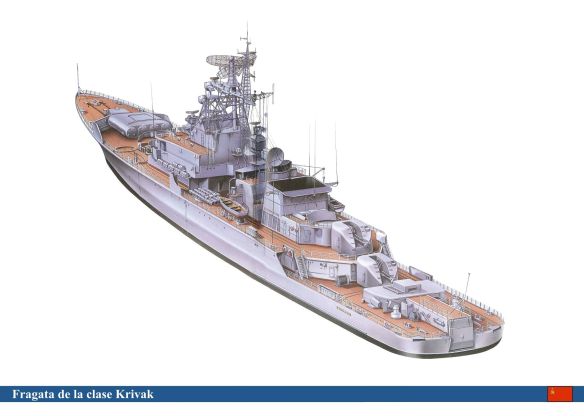

All this led to navies pursuing two completely different paths of surface warship development. Smaller navies could no longer afford oceangoing ships equipped with all of these systems. This forced them to seek smaller ships that carried weapons and sensors more suited to the missions of coastal defense, environmental protection, and patrol and control of economic exclusion zones.

The rebirth of mine warfare after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War also rejuvenated interest in mine countermeasures ships in the U. S. Navy and in Asian navies. (North Korea’s and Europe’s navies had never lost interest in mine warfare.) General-purpose corvettes with limited AAW and ASW capabilities and mine countermeasures ships have become the predominant units of the world’s smaller navies. Occasionally, these navies employ frigates as their flagships and on long-distance patrols, but 900-1,100-ton corvettes are these navies’ workhorses. Destroyers and 10,000-ton all-purpose guided missile cruisers are found only in oceangoing navies-those whose country can afford the ships and the expensive shore facilities and ocean surveillance networks required to support their operations.

Surface ships execute the majority of naval operations, from show-the-flag and gunboat diplomacy, through disaster relief and emergency evacuation operations, to land attack and maritime transport operations. Although the combatant ships garner the headlines and are most often featured in the recruiting posters, a balanced fleet includes tankers, transports, repair and rescue ships, and even range and telemetry ships to help with the calibration of weapons systems and electronics. The Cold War saw these ships evolve from the simple, manually operated systems and uncomplicated designs of World War II to the highly automated, lightly crewed ships of today. Moreover, the Cold War’s end brought new missions beyond the traditional ones of the past. Environmental and resource concerns and disaster relief are now major naval missions, and ship designs are being modified to accommodate those new missions.

References Isenberg, Michael T. Shield of the Republic: The United States Navy in an Era of Cold War and Violent Peace, Vol. 1, 1945-1962. New York: St. Martin’s, 1993. Pavlov, A. S. Warships of the USSR and Russia, 1945-1995. Translated from the Russian by Gregory Tokar. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997. Polmar, Norman, et al. Chronology of the Cold War at Sea, 1945-1991. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997. Raymond, V. B. Jane’s Fighting Ships, 1950-51. London: Jane’s, 1951. Sharpe, Richard. Jane’s Fighting Ships, 1989-90. London: Jane’s, 1990. Sondhaus, Lawrence. Navies of Europe, 1815-2002. London: Pearson Education Limited, 2002. Watson, Bruce W., and Susan M. Watson, eds. The Soviet Navy: Strengths and Liabilities. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1986.