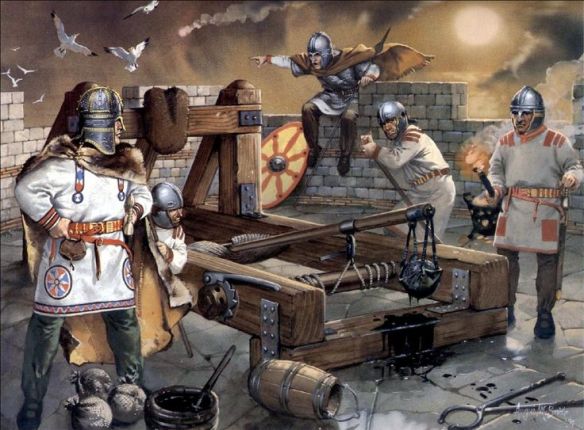

Late Roman artillery at the Saxon shore.

The ballista, plural ballistae, was an ancient missile weapon that launched a large projectile at a distant target. Developed from earlier Greek weapons, it relied upon different mechanics, using two levers with torsion springs instead of a prod, the springs consisting of several loops of twisted skeins. Early versions projected heavy darts or spherical stone projectiles of various sizes for siege warfare. It developed into a smaller sniper weapon, the scorpio, and possibly the polybolos.

The legionaries were well equipped with artillery: a figure of around 60 machines per legion is found in both Josephus (Jewish War 3.166) and Vegetius (2.25). The machines were of various sizes: Trajan’s Column shows both man-portable boltthrowers (manuballistae, cheiroballistrae) and those mounted on a mule-drawn carriage (carroballistae) (Scenes 65-66). Range and accuracy were impressive: at Hod Hill in Dorset, a hill-fort probably captured by Legio II Augusta in ad 43, 17 bolt-heads have been found, still embedded in the chalk where they struck. Eleven had hit Hut 37 (dubbed by archaeologists the “Chieftan’s Hut”), landing in a ten-meter circle, including four that landed in a three-meter circle, all from an estimated range of 170 meters. Of the six other shots it is likely that some at least were initial ranging shots, from which the firers corrected their aim. A reconstructed cheiroballistra has achieved similar results. Although crucial in sieges and assaults, artillery was used in field battles too: at Cremona in ad 69, an “enormous ballista,” of the Fifteenth Legion threw “huge” stones at the Flavian army; only by disguising themselves with the shields of fallen Vitellian troops did two bold individuals put it out of action, by cutting the twisted cord springs which provided its torsion (Tacitus, Hist. 3.25) – a key vulnerability of such machines.

The crews of the field artillery were specialists but were never formed into specific separate units. Instead they were drawn from the legionary centuries to man the machines and presumably to look after them and repair them. The artillerymen were immunes and did not have to perform routine fatigues.

Roman artillery was of two kinds, single or double – armed, although the single – armed stone thrower did not come into use until the fourth century (Goldsworthy, 2003). Caesar uses the general description tormenta when writing of artillery, without distinguishing between the different types of machines. There is some confusion among ancient and modern works about the terminology applied to Roman artillery, in that catapulta as mentioned by Vitruvius (De Architectura 10.10) appears less frequently in modern works than the term ballista, which is often employed for all types of machines whether they shot arrows or stones. Strictly, the catapulta fired arrows or bolts, and the ballista fired stone projectiles (Bishop and Coulston, 1993), but since they operated in the same manner by torsion, like a large crossbow, perhaps the distinction is not so important. Marsden (1969) says that catapulta was the main term in use until the fourth century ad, and then ballista superseded it. A further complication concerns the names of the one-armed machines. The slang term scorpio, or scorpion, is used in the first century ad by Vitruvius to describe the two-armed catapulta, but in the later Roman period Ammianus (23.4.4-7) says that it was used of the single-armed stone thrower, because of its upraised sting. This type of machine was also nick named onager or wild ass, descriptive of its violent kick.

The ancient Greeks had already worked out most of the problems of bolt-shooting and stone-throwing artillery, such as how to draw the bowstring back, how to hold it in place until ready for firing, and how to release it with sufficient force to shoot the projectile (Landels, 2000). The material used in bundles for the torsion springs must be fairly elastic but not so much that it stretches too easily, and it must be capable of being woven into a rope to hold the ends together. The ancient engineers used sinew or hair, perhaps horsehair, but especially favored was human hair, especially women’s hair. The bundles were gathered together at the ends, and a rod or lever was inserted into them at right angles, then twisted to create the torsion effect, and housed in a wooden casing strengthened by a metal frame. The springs were placed on washers. The two arms of the machine were inserted into the springs and joined together at their opposite ends by the bowstring, which Vitruvius says could be drawn back by several means, by windlass, block and pulley, or capstan (De Architectura 10.11). It was especially important to ensure that the two arms were pulled back equally to give them equal thrust; otherwise the missile would go off course (Landels, 2000).Vitruvius explains that the remedy for this was to tune the strings, which he says should respond with the same sound on both sides when struck by the hand (De Architectura 10.11.2).