The plane of VVS of 40th Army commander assistant, sub-colonel A.Rutskoi. It was shot down on 4-th August 1988 over Afghanistan.

Alexander Rutskoi flew fighter planes for the Fortieth Army. The thirty-one-year-old colonel, the son of a tank officer from the southern Kursk Region, had been assigned in 1985 to train three squadrons of mostly young lieutenants to fly the Su-25. Two of the squadrons would be based in Bagram, the third in Kandahar.

Decades earlier, Nikita Khrushchev had directed the Soviet Air Force to focus on strategic bombers and supersonic fighters instead of ground-attack aircraft. The recent arrival of the Su-25 marked one of the first major advances in the development of close air support of infantry since its prominent role in World War II, when Soviet pilots had provided vital help to infantry units facing the Wehrmacht. Rutskoi liked the new plane. Nicknamed grach, or crow, the squat, low-flying Su-25 was armed with a twin-barrel 30-mm cannon and had ten pylons under its wings that could carry thousands of pounds of weapons, including thousand-pound RBK cluster bombs, and 57-mm to 330-mm rockets. In addition to being well armed and armored, and configured for providing very close support of ground forces, the plane took rough handling well.

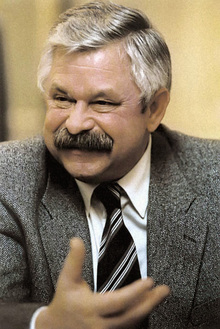

Compact, mustachioed Rutskoi, whose prematurely graying hair improved his good looks, had a reputation for independence and speaking his mind to his fellow officers. Rather than hold him back, those qualities had served him well, rare as that was. Now he’d been trusted to develop tactics to maximize the new fighter’s effectiveness in the dusty and otherwise adverse weather conditions often encountered when flying in hazardous mountain terrain. It was a dangerous task; Rutskoi’s predecessor had lost twelve pilots.

Fighter pilots, like their counterparts flying helicopters, rotated through Afghanistan every year, and although only parts of regiments were often deployed, there were many units. Even though helicopters were the Fortieth Army’s main air weapon, fixed-wing planes had played an important part in the war, and not only the long-winged Tu-16 and pointy-nosed Tu-22 bombers that carpet-bombed the Panjshir Valley and other areas in preparation for ground attacks. Agile MiG-21 fighters had been used as attack planes early in the conflict, but the aging craft had primitive radars, carried relatively light weapon loads, and had not been designed for close ground support. Heavier MiG-23s, which were more effective in that role, replaced many of them over the years, as did Su-17s, which carried large weapons loads.

When Rutskoi landed at the Bagram air base, it was under attack. Incoming mortars and rockets were severing heads and limbs in a battle raging on the green plain between the base and Charikar at the foot of the Panjshir Valley. “Where the hell have I arrived?” the young colonel thought. Rutskoi took some revenge later, when he came to command the base. He gathered local Afghan elders in order to warn them he would obliterate any areas used to attack the base. “I’ll turn it into the Gobi desert,” he vowed. When the next attack came two weeks later and he delivered on his promise, the attacks ceased, at least when he was known to be on the base.

Rutskoi’s squadrons were among the first to fly at night, when most caravans moved through the Hindu Kush passes, and rebels planted mines. But the cover of darkness was also useful for the Soviets: spetsnaz fighters carried out many of their ambushes and other operations at night. Highly dangerous as it was, night flying could also be highly effective. When nervous mujahideen unleashed volleys of antiaircraft fire, it was relatively easy to see from the air where it came from, then destroy the rebel positions.

Rutskoi developed a reputation for dependability. During a 1986 attack on the Panjshir Valley led by Fortieth Army Chief of Staff Yuri Grekov, mujahideen counterattacked the Soviet command center from several sides. After air squadron commanders had rebuffed Grekov’s order for air strikes because the weather was too cloudy, Grekov radioed Rutskoi in Bagram.

“How fast is the wind blowing?” the colonel asked. “And from what direction?”

Although Grekov didn’t know, he pressed a reluctant Rutskoi to bomb the mujahideen. Rutskoi relented. Flying into the valley, he dropped four massive cluster bombs and listened for the result. The explosives went off dangerously close to the Panjshir command point. It now maintained radio silence-until he heard a stream of swearing. “You fucking bastard! What the hell do you think you’re doing!?” The fury came from Grekov. “How close did you have to drop those things? We’re scraping ourselves off the ceiling!” However, the general later sent Rutskoi a case of Armenian cognac for saving the command point from immediate danger.

Helicopters rarely flew at night, when Rutskoi’s squadrons were often called on to support spetsnaz pinned down in narrow valleys. The pressure was intense; pilots wore special camel-hair jumpsuits to help wick away rivers of sweat. On long missions, they violated regulations by flying on one engine to conserve fuel. Attacking caravans in mountain passes, they sought to hit the first and last vehicles, then swooped back to finish off the others. Rutskoi’s squadrons sometimes flew up to eight sorties a day, far more than earlier units had. His own plane was hit often. Parts of it were burning during four very tricky landings at his base.

In 1987, mujahideen fighters shot down six Afghan Mi-8s close to a major rebel base in Zhawar near the Pakistani border. The Soviets had taken the complex at great cost from rebel commander Jallaladin Haqqani two years earlier, only to surrender it again when the attacking force withdrew. Rutskoi was given a reconnaissance mission to attract fire to himself over the rugged mountain terrain while another pilot photographed the source of the attacks. Five miles east of Zhawar, a U. S.-built Stinger missile found his right engine while he was flying at 150 feet. The aircraft started spinning, but with its left engine still working, Rutskoi regained enough control to clear the valley from where the missile was fired-but only until a burst from an antiaircraft gun sent the plane crashing to the ground in a no-man’s-land between mujahideen and Afghan Army positions.

His back was broken and his head and a hand were injured, but Rutskoi managed to crawl from his cockpit and see mujahideen and Afghan soldiers making for him as quickly as possible from opposite sides. An Afghan BTR got there first under heavy fire, some of which caught a captain in the back during the rescue.

Hospital doctors told Rutskoi he’d be confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. He began physical therapy three months later, using a course developed to prepare Soviet cosmonauts-and made fast progress. He was back in the air within months. Promoted to deputy head of Soviet Air Force training in late 1987, he planned to make himself eligible to join the top brass by enrolling in the General Staff Academy. But the following year he was sent back to Afghanistan as deputy head of the Fortieth Army air forces.