To the individual combat soldier, the bitter cold weather of January had added to the discomfort of fighting in mud and water. Wet foxholes were the rule, freezing nights the norm, and trench foot and illness the result. A sharp rise in artillery expenditure rates during the last ten days of the month seemed to have little effect, and, added to other causes for concern, gave “every evidence that the enemy intends to prevent, at all costs, the occupation of Rome and juncture of the main Fifth Army with the Anzio forces.”

The estimate was correct. On 31 January, when Vietinghoff informed Kesselring that he intended to continue to hold his ground, he indicated that the focal point of his defense was the Cassino massif. If he needed to reinforce the XIV Panzer Corps to prevent the Fifth Army from breaking through, he would weaken the LXXVI Panzer Corps by taking troops from the Adriatic front.

Kesselring was satisfied. “In full agreement with intentions as reported,” he said.

At the beginning of February, the Germans had a dual task: eliminate the Anzio beachhead and hold the Gustav Line. The Allied lodgment, if expanded sufficiently to threaten the major lines of communication running south from Rome, would compel the Germans to abandon the Gustav Line and give up southern Italy. Yet the Allied pressure around Cassino to gain entrance into the Liri valley made it impossible for the Germans to divert forces to Anzio from the Gustav Line. In fact, the attacks against the Gustav Line required that more strength be concentrated along the Rapido-Garigliano line than had ever before been committed against the Fifth Army, so much more that Kesselring would have to draw on his strength at Anzio to bolster the Gustav defenses early in February. If the Gustav Line could be held until enough units were gathered at Anzio to eliminate the beachhead, the situation in southern Italy would remain the same as it was before the amphibious operation. The Allied forces would have suffered a crushing defeat and would still be a considerable distance from Rome.

The four German divisions that had been fully committed along the Gustav Line early in January had been increased by the beginning of February to an equivalent of about six divisions, and additional units would appear almost daily despite the requirements of Anzio. Opposite 10 Corps, the 94th Division occupied the coastal area, its eastern flank bolstered by part of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division. Against II Corps were parts of the 15th Panzer Grenadier, the 71st Infantry, and the 3d Panzer Grenadier Divisions, all of which also had units at Anzio, and the entire 44th Infantry Division. Facing the French were part of the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division and the entire 5th Mountain Division.

All these organizations except the 29th Panzer Grenadier and 71st Divisions had been in the line continuously for at least a month and most of them for longer. All were seriously depleted, the 71st in particular, and not enough replacements were coming in to return the units to full strength. The 44th Division, for example, had received approximately 1,000 replacements in January but had lost the same number as prisoners.

In the critical sector, the area immediately around Cassino, the 44th and 71st Divisions, as well as a few units of the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division, had received a battering as they held tenaciously in the hills north and west of the town. To augment these troops and at the same time permit the relatively strong 29th Panzer Grenadier Division to move to Anzio, Vietinghoff would transfer the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division to the Cassino area from the Adriatic coast; units would begin arriving piecemeal around 7 February. A day or so later the 1st Parachute Division would come from the Adriatic front, to be joined at the Gustav Line by units of the division that had earlier been rushed to Anzio. The veteran paratroopers would take positions in the hills behind Cassino. Monte Cassino would become their fortress.

The German Defenses

The Germans had closed the gateway to the Liri valley with formidable defenses along two lines, or, more properly, zones, that they had constructed across the peninsula from Ortona on the Adriatic to the mouth of the Garigliano River on the Tyrrhenian Sea. One of these two lines the Germans had named Gustav. Crossing Italy at its narrowest, the line incorporated some of the best defensive terrain on the peninsula. It extended almost a hundred miles northward to the Adriatic coast, which it reached at a point some two miles northwest of Ortona.

The most heavily fortified part of the Gustav Line was the central sector, opposite the Eighth Army. Anchored on Monte Cairo, the 5,415-foot summit of the mountain massif forming the Liri valley’s northern wall, this sector of the Gustav Line followed the high ground southeast to Monte Cassino, then ran south along the west banks of the Rapido and Gari Rivers across the entrance to the Liri valley and a terminus on the southern slopes of Monte Majo. From Monte Majo’s eastern foothills the line continued south of the village of Castelforte, where it turned southwestward along high ground north of Minturno and thence on to the sea.

With steep banks and swift-flowing current the Rapido was a formidable obstacle, and the Germans had supplemented this river barrier with numerous fieldworks. Along the river’s west bank stretched a thick and continuous network of wire, minefields, pillboxes, and concrete emplacements. Between the Rapido and the Cassino-Sant’Angelo road, the Germans had dug many slit trenches, some designed to accommodate no more than a machine gun and its crew, others to take a section or even a platoon.

The entire fortified zone was covered by German artillery and mortar fire, given deadly accuracy by observers located on the mountainsides north and south of the Liri valley. Allied forward observers and intelligence officers estimated that there were about 400 enemy guns and rocket launchers located north of Highway 6 in the vicinity of the villages of Atina and Belmonte, respectively, nine and six miles north of Cassino. Of these the British believed that about 230 could fire into the Cassino sector, and about 150 could fire in support of the defenders of Monte Cassino and Cassino town.

Opposite the Fifth Army sector, however, only a small portion of the Gustav Line was still a part of the defensive positions that the Germans had selected in the autumn of 1943, for south of the Liri valley the front followed a line where the British 10 Corps had established a bridgehead beyond the Garigliano during the winter fighting. This meant that in some areas facing the Fifth Army the Germans were holding a defensive line not of their own choosing and that in some sectors (the French, for example) the Allies rather than the Germans possessed high ground overlooking the enemy positions.

The Gustav Line was a zone of mutually supporting firing positions–a string of pearls, Kesselring called them. While those sectors of the line located in the Liri valley and along the coastal corridor were relatively deep defensive zones, ranging from 100 to 3,000 yards in depth, those in the mountains were much thinner, partly because the rocky terrain made it extremely difficult to dig or build heavier defenses, but mainly because the local German commanders doubted that the Allies, unable to use armor and artillery there, would choose to attack through such forbidding terrain. In any event, an attack over the mountains, they believed, would be relatively easy to stop.

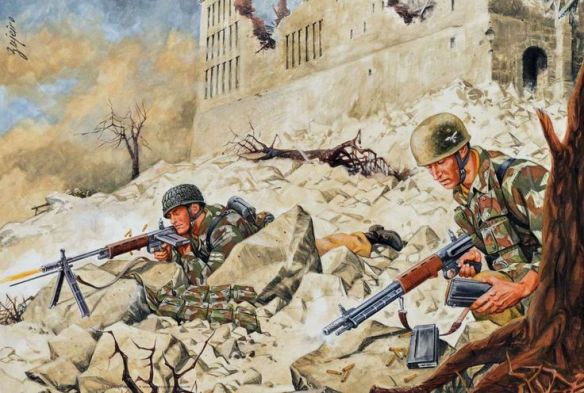

Except for barbed wire, railroad ties, and steel rails, the materials used in constructing the Gustav Line positions were readily obtainable on the site. Whenever possible the Germans utilized the numerous stone houses of the region as shelters or firing positions. Locating machine guns or an antitank gun in the cellar, enemy troops piled crushed stone and rubble on the ground floor to provide overhead protection. If bombs or shells destroyed the upper part of the house, the additional rubble would simply reinforce this cover. Allied troops would frequently fail to detect these cellar positions, sometimes not until hours after a position had been overrun and the Germans had opened fire on the rear and flanks of the assaulting troops.

Firing positions for infantry weapons were mostly open but usually connected by trenches to covered personnel shelters. The shelters ranged from simple dugouts covered with a layer of logs and earth to elaborate rooms hewn out of solid rock, the latter often used as command posts or signal installations. Invariably well camouflaged, most infantry shelters were covered with rocks, earth, logs, railway ties, or steel rails.

Behind the Gustav Line the Germans had constructed the other defensive zone–the Fuehrer Riegel, or the Hitler Line. This line lay from five to ten miles behind the Gustav Line. Beginning on the Tyrrhenian coast near Terracina, twenty-six miles northwest of the mouth of the Garigliano and the southern gateway to the Anzio beachhead, the Hitler Line crossed the mountains overlooking the coastal highway and the Itri-Pico road from the northwest and west, and thence the Liri valley via Pontecorvo and Aquino to anchor at Piedimonte San Germano on the southern slope of the Monte Cairo massif. Although essentially a switch position, as its name implied, the line was made up of fieldworks similar to those in the Gustav Line and was, at least in the Liri valley sector, as strong as or, in some instances, even stronger than the latter.

Manning the German defense system on the southern front was the equivalent of about nine divisions. One of these was in reserve; the remainder were divided among two regular and one provisional corps headquarters. All were under the command of the Tenth Army. The XIV Panzer Corps, commanded by Generalleutnant Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, held a sector of the Gustav Line extending from the Tyrrhenian coast across the Aurunci Mountains to the Liri and a junction with General der Gebirgstruppen (General of Mountain Troops) Valentin Feuerstein’s LI Mountain Corps. Along the panzer corps’ front were the 94th Infantry Division in the coastal sector, and the 71st Infantry Division in the Petrella massif. A composite Kampfgruppe made up of a regimental group detached from the 305th Infantry Division and a regiment from the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division lay between the 71st Division and the Liri River. The remainder of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division was in corps reserve and watching the coast.

In the LI Mountain Corps sector the 44th Infantry (H u. D) Division manned the valley positions, and the elite 1st Parachute Division continued to hold the Monte Cassino sector, including the town of Cassino. In the mountains north of the Monte Cairo massif the 5th Mountain Division and the 144th Jaeger Division held the corps’ left wing to a junction with Generalleutnant Friedrich Wilhelm Hauck’s provisional corps, Group Hauck. The latter held a quiet sector about eight miles southeast of the Pescara River on the Adriatic coast with the 305th and the 334th Infantry Divisions and the 114th Jaeger Division in reserve. In front of the Allied beachhead at Anzio lay the Fourteenth Army with its five divisions divided between the I Parachute Corps and the LXXVI Panzer Corps. One of these five divisions was located along the coast northwest of Rome as a precaution against an Allied amphibious landing attempt.

As a mobile strategic reserve under Army Group C’s control, Kesselring held the 3d and 90th Panzer Grenadier Divisions and the 26th Panzer Division in the vicinity of Rome, and, some thirty miles to the north near Viterbo, the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division. In northern Italy, serving mainly as a coast defense force, was Army Group von Zangen, consisting of the 162d (Turkomen) Infantry Division, the 356th Infantry Division, the 278th Infantry Division, and the 188th Mountain Division, none of which were first-rate units. Except for von Zangen’s group, all of the reserve divisions were first-rate and could, if committed soon enough, have an important influence on the outcome of the fighting. Yet their dispositions, partly determined by Kesselring’s reaction to Allied deception plans, made it unlikely that they could, or would, be able to reach the southern front in time to influence the tide of battle. For the most part, however, Kesselring’s veteran divisions were located in defensive zones well sited in relation to terrain that favored the defense. If properly manned, the Gustav and Hitler Lines well merited Kesselring’s confidence that the gateway to the Liri valley and to Rome was reasonably secure.

In making preparations to meet an expected Allied offensive, the German armies in Italy were left largely to their own resources. Since the increasing pressures against the front in Russia and the growing danger of a cross-Channel invasion precluded any significant reinforcement of Kesselring’s command above the normal replacement flow, support from Hitler and the OKW was limited for the most part to exhortations to stand firm. The best the OKW could do for Kesselring was to postpone indefinitely the scheduled transfer from Italy to France of the Parachute Panzer Division “Hermann Goering,” a unit of the OKW reserve located near Leghorn, well over 200 miles away from the southern front.

Nevertheless, from March through April 1944, in spite of the efforts of the Allied air forces through Operation STRANGLE to prevent German reinforcements from reaching the front, German troop strength and matériel in Italy had increased, though modestly. Although no major units had moved into the theater, the flow of replacements and recovered wounded exceeded a casualty rate reduced by the April lull in the fighting, and the assigned strength of the German army units rose from 330,572 on 1 March to 365,616 on 1 May 1944.

In addition to assigned strength, the Tenth and Fourteenth Armies on 1 May 1944 also had approximately 27,000 men attached from the Luftwaffe and the Waffen-SS. One division and miscellaneous small Luftwaffe ground units in von Zangen’s group accounted for an estimated 20,000 more. Thus, on 1 May 1944 the total German ground strength, including army, SS, and Luftwaffe ground units, assigned to the Italian theater numbered approximately 412,000 men. But this force was scattered from the fronts south of Rome to the Alpine passes far to the north.

Although most German units in 1944 were plagued by a shortage of well-trained junior officers and noncommissioned officers, units in Italy had yet to suffer seriously from a growing manpower shortage afflicting German forces elsewhere. Several expedients, such as the “combing out” of overhead units and using foreign auxiliaries for housekeeping and labor duties, enabled the Germans to meet their manpower requirements. For these reasons, in early 1944 OB Suedwest commanded forces superior in quality to the average German unit in other OKW theaters of operation.

Nineteen of the 23 divisions in Kesselring’s Army Group C as of 1 May 1944 were considered suitable for the defensive missions they might be required to accomplish. The German commanders deemed only two of these divisions qualified for any offensive mission, 11 for limited attacks, 6 for sustained defensive action, and 4 for small-scale defensive action. Thus approximately half of the divisions, an unusually high proportion at that stage of the war, were rated capable of some offensive action.54

The relative quiet on the battlefronts in April had enabled Kesselring to disengage several of his better divisions–among them the 26th Panzer and the 29th and 90th Panzer Grenadier Divisions–for movement to the rear for rest and rehabilitation. Together with the Hermann Goering Division and several other divisions of lesser quality that were training, fighting partisans, or guarding the coasts, these disengaged formations made up the general and theater reserves available to Kesselring.55

In the disposition of his general reserves Kesselring had to consider three important factors. First, the existence of two fronts south of Rome made it desirable to place reserves so that they could be quickly shifted to either front. Second, thanks to the Allied deception plan, so vulnerable did he regard the coastal sectors north as well as south of the Anzio beachhead that he believed a number of powerful and highly mobile units were necessary to back up the weak forces guarding that area of the coast. Finally, the possibility that the Allies might try to cut the few roads between Rome and the southern front by means of an airborne landing in the vicinity of Frosinone, some fifty miles southeast of Rome, required a division in that area. Although Kesselring made strenuous efforts to satisfy all three requirements, whatever success he achieved was bought at the cost of dividing some of his best divisions among two or more widely separated groups.

The Germans clearly had been taken in by the Allied deception plan. In the area selected by the Allies for their main effort–the Liri valley–the enemy had underestimated Allied strength by seven divisions. For example, opposite the XIV Panzer Corps in the Allied bridgehead beyond the Garigliano General Juin had managed to assemble four times the number of troops his adversaries had estimated to be under his command. On the other hand, German intelligence credited the Allies with much larger reserves than they actually had and believed that three divisions were in the Salerno-Naples area engaged in landing exercises preparatory for another amphibious operation. Kesselring had disposed his forces on that assumption. A minimum number of troops was in line and several reserve divisions were positioned along the coast to counter expected landings. That was to prove a vital factor in the early battles of the coming offensive.

While some ground combat troops in Italy belonged to the Luftwaffe, as, for example, the Hermann Goering Division, actual German air strength was negligible. Compared with the approximately 4,000 operational aircraft the Allies could muster in Italy and on the nearby islands, the Luftwaffe had only 700 operational aircraft in the central Mediterranean area. Of this number less than half were based in Italy. Of these only a small percentage would ever rise to challenge the overwhelming Allied air forces or to harass Allied ground movements. German air commanders were carefully husbanding their few aircraft for those occasions that might give some promise of success against a new Allied amphibious landing or, in conjunction with the greater air strength in Germany and France, against the expected Allied invasion attempt in northwestern Europe.