USS Chesapeake, depicted in a c.1900 painting by F. Muller

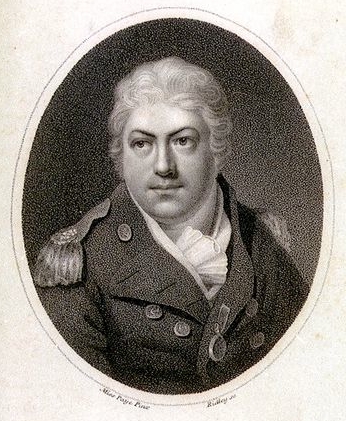

British admiral. Born on 10 August 1753, at Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire, the second son of the fourth Earl of Berkeley, George Cranfield Berkeley was a member of one of England’s oldest aristocratic families. He attended Eton during 1761–1766, after which he entered the Royal Navy as a midshipman. Promoted to lieutenant in 1772 and to commander in 1778 when he took command of a sloop, his advancement in the navy was delayed because of his Whig political connections.

In 1780 Berkeley was appointed to a frigate as a post captain. He went on half pay in 1783 with the end of the War of American Independence, during which he had served in the Newfoundland Squadron and in the Channel and Mediterranean Fleets, and had fought at Ushant in 1778 and at Gibraltar in 1781.

Elected to Parliament from Gloucestershire in 1783, Berkeley was regularly reelected until 1810. His parliamentary career was not distinguished, however. A strong supporter of William Pitt’s government, he was named surveyor-general of the ordnance in 1789. At the outbreak of the French Revolutionary War in 1793, he took command of the Marlborough, a 74-gun ship in the Channel Fleet. He was severely wounded in the head in the Battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794. Although he received with other officers the thanks of Parliament and one of the gold medals awarded, he was later accused of being a “shycock” in battle who “skulked in the cockpit.” He brought suit for this libel and won a favorable verdict.

On recovery from his injury, Berkeley in 1798 received command of the Sea Fencibles, the maritime militia along the Sussex coast. In 1799 he was promoted to rear admiral, and for the next two years he commanded a squadron in the Channel Fleet, first under Lord Bridport and then under Lord St. Vincent, who was critical of his performance. While St. Vincent was first lord of the Admiralty, Berkeley received no appointment, but in 1804, with the return of Pitt to office, he was made head of the Sea Fencibles for all of England.

Promoted to vice admiral in 1805, he was finally given an independent command in 1806 by the Grenville-Fox government when he became commander in chief of the North American Squadron. Because of his volatile temperament, his friends in the government were apprehensive about his suitability for an assignment that involved sensitive relations with the United States.

In the United States Berkeley soon became exasperated with the desertion of British seamen while his squadron was woefully undermanned. In June 1807 he issued the fateful order to stop and search any armed vessel suspected of having British seamen aboard. This led to the HMS Leopard’s firing on the American frigate Chesapeake off the Virginia Capes, the killing of three American seamen, the wounding of 18 others, and the removal of four seamen claimed to be British subjects. While Berkeley’s action in the circumstances may have been justified, war with the United States became a distinct possibility and the British government prudently disavowed the act and recalled him. Because of his influential connections, no further action was taken against him, and in late 1808 he was appointed commander in chief of the Lisbon Squadron, a post he held for three years.

Berkeley and the Duke of Wellington were closely associated during the Peninsular War. In 1810 Berkeley was made a full admiral, and that same year Portugal designated him Lord High Admiral in appreciation of his services. Berkeley’s active naval service ended with his retirement from the Lisbon command in 1812. Disappointed that he did not receive a peerage for his service, he was made a Knight of the Bath in 1813. Berkeley died in London on 25 February 1818.

Chesapeake-Leopard Affair (22 June 1807)

Most important naval confrontation between the United States and Britain in the years before the War of 1812 and a cause of that conflict. In 1807 several French warships sought refuge in Chesapeake Bay. Royal Navy ships then took up station off the coast to wait for the French to head to sea; during the wait a number of British seamen deserted. Some of them found their way aboard U.S. Navy ships, including the frigate Chesapeake (40 guns). British authorities complained about these desertions to the Americans, but to no avail.

On the morning of 22 June 1807, the Chesapeake weighed anchor and sailed from Hampton Roads for the Mediterranean. Commodore James Barron, the new commander of the Mediterranean Squadron, had nominal command. He had visited his ship only twice prior to sailing. Master Commandant Charles Gordon prepared her for sea.

As the Chesapeake tacked to get offshore, the HMS Leopard of 50 guns, commanded by Captain Salusbury Humphreys, came up and hailed her. The Leopard’s captain said that he had dispatches. But the sole “dispatch,” brought aboard by a British lieutenant, turned out to be a general circular from Vice Admiral Sir George Berkeley, the Royal Navy commander in North America, ordering his captains to search for deserters from specified British warships.

Humphreys, who did his best to modify the order, nonetheless insisted on the right to muster the Chesapeake’s crew. Barron denied that he had deserters on board and, in any case, refused the British right to search a U.S. Navy warship. After more than 40 minutes of fruitless discussion, Humphreys recalled the lieutenant and ordered his crew to open fire. The Chesapeake was wholly unready and her crew got off only one shot before Barron struck. In the uneven exchange (the British fired several broadsides), three Americans were killed and 18 others, including Barron, were wounded. One of these soon died of his wounds. Humphreys refused Barron’s surrender of the Chesapeake as a prize of war, mustered her crew, took off four men identified as deserters, and sailed away.

There was an immediate explosion of indignation in the United States and even a clamor for war. President Thomas Jefferson set himself against this war fever. In July, however, he ordered British warships from American waters. Although the passions for war soon cooled, the affair had important repercussions for Anglo-American relations.

Barron was found guilty of neglecting to clear his ship for action, was suspended from the navy for five years, and never again held a command afloat. Gordon was not penalized, perhaps owing to family connections. Ultimately, London admitted that a mistake had been committed and the two survivors of the four taken off the Chesapeake were returned. The U.S. Navy did order a halt to recruitment of foreigners on its ships, and it would achieve a measure of revenge in the President–Little Belt encounter of 18 May 1811.

References Fisher, D. R. “Hon. George Cranfield Berkeley.” In The History of Parliament, the House of Commons, 1790-1820, ed. R. G. Thome, 5 vols., 3: 191-193. London: Secker & Warburg, 1986. Gentleman’s Magazine 58, 1 (April 1818): 370-371. Howard, David D. “Admiral Berkeley and the Duke of Wellington: The Winning Combination in the Peninsula.” In New Interpretations in Naval History, ed. William B. Cogar, 105-120. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989. Naval Chronicle 12 (July-December 1804): 89-113. Tucker, Spencer C., and Frank T. Reuter. Injured Honor: The Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, June 22, 1807. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996. Tucker, Spencer C., and Frank T. Reuter. Injured Honor: The Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, June 22, 1807. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996.